Many of us are familiar with the national anthem of the United States of America: It’s presence at countless sporting events and televised competitions offers a display of patriotism and a national musicality. Recently, the reaction to players in the NFL kneeling during the national anthem as a protest against police brutality in the country has sparked conversation and controversy. But long before players took a knee during the national anthem, there were other controversies surrounding the performance practice of a song meant to unify and represent an entire nation.

Throughout history, there have been widespread reactions in the American public backlashing against performances of the anthem deemed incorrect, inappropriate, or inconsistent with a sort of ideal performance. Recent examples include comedian Roseanne Barr’s controversial performance of the anthem at a Major League Baseball game in 1990 which drew rebuttal from the public as well as the US President at the time. More recently, American pop singer Fergie performed an allegedly jazzed-up version of the anthem, but her unique rendition drew criticism and laughter from players and fans, and went viral.

But where do these different versions of the anthem come from? Shouldn’t a national anthem be consistent, unchanging, and notated in stone? Why has our national anthem changed so much? The answer seems to be found in the earliest times of musical notation of the anthem. Drawing on sheet music found in the UCLA Sheet Music Consortium, we see a handful of different arrangements and publishers trying their hand at notating the national anthem. In scans of arrangements spanning roughly 1840-1970, there are already plenty of different notations and variations within the anthem and its arranged accompaniment.

While some arrangements are clearly named and marketed as a sort of theme and variations of the national anthem, others are simply entitled “The Star Spangled Banner” and fail to list an arranger (and sometimes a composer). Although some of the arrangements give compositional credit to Francis Scott Key, it is unclear who had written the embellishments and variations in some of these arrangements. However, what is clear from these pieces is that from very early on in the American musical life of The Star Spangled Banner, there were liberties taken with arranging and performing the piece- a rather American mindset.

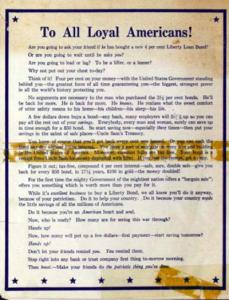

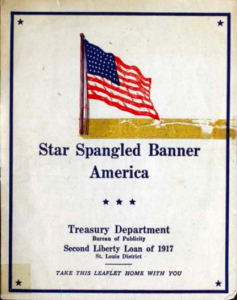

Screenshots from a government issues pamphlet with choral harmonizations to the Star Spangled Banner.

Some things have remained consistent, which should be noted. For example, many of the arrangements have marked con spirito, a rather unique and distinct marking that is found in many of the arrangements of this time period. While I could not find any sources that dove into arrangements of the anthem specific to this time period to further discuss marking such as the con spirito found in so many, I speculate that even though arrangers felt at liberty to try new things, they felt a sort of obligation to maintain specific aspects of the piece’s identity. This is also reflected in other similarities between the arrangements: most are in the same key, have the same exact notated melody, and include similar harmonization. Although The Star Spangled Banner would not officially be adopted until 1931, the artistic license to embellish, recreate, and change the piece had been established long before. Since then, American performers had the autonomy to take risks and try new ideas with our national anthem with and without public support.

Primary Sources

A Whig Of Providence. TheWhigs of Columbia shall surely prevail. Oliver Shaw, Providence, monographic, 1840. Notated Music. https://www.loc.gov/item/sm1840.371540/.

Rziha, Francis. Star Spangled Banner. W. C. Peters, Baltimore, monographic, 1850. Notated Music. https://www.loc.gov/item/sm1850.140860/.