American audiences at the turn of the twentieth century loved watching performances that had a sense of authenticity. White Americans viewed blackness as the most authentic form of cultural expression, while the nation was still whirling with the lasting effects of minstrelsy. Black performers and musicians used America’s fascination with the “other,” authenticity, and minstrelsy to their advantage. Among these black performers, are the duo of Bert Williams and George Walker that used their race and talent as a marketing tactic to increase their cultural value, further their careers, and deliver the authenticity Americans craved while paving the way for other black musicians.

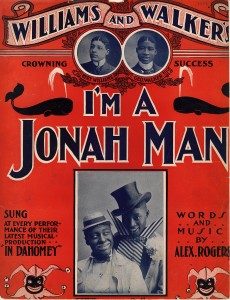

When Bert Williams met George Walker in 1893, they were very amused with watching white actors in blackface try to act natural on stage and dub themselves as “coons.” Walker remarks “We thought that as there seems to be a great demand for for black faces on stage, we would do all we could do to get what we felt belonged to us by the laws of nature.” 1 Billing themselves as “the two real coons,” the duo headed to New York surrounding themselves with talented members of their race, such as H.T. Burleigh among other recognizable names. With a show behind their name, Williams and Walker were able to put a premium on cakewalk. In 1903, the duo debuted their show Dahomey, at the New York Theater and the first black, comedy musical on Broadway. Below is a poster for the show’s most famous song.

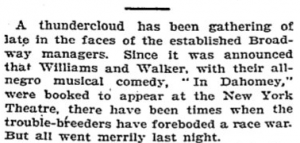

The show was widely successful, making a tour in Europe for the future King of England, Edward the VIII. William and Walker did not emphasize the ragtime rhythms and coon song stereotypes that dominated their field, nor the exaggerated, high kneed cakewalk. Instead, they demonstrated how smooth, beautiful, and sensational it could be. Additionally, jokes the pair made were not targeted at race differences as seen by the white minstrels, but by universal situations or characters like a “downtrodden” everyone could laugh at.2 They pitched their “real blackness” at audiences to draw crowds to an authentic “black style.” The duo danced a middle ground between thunderous applause and being thrown off the stage solely for being black by their audiences. Below, is a review by the New York Times after one of their shows.

Even though both actors were black, Williams wore blackface to make his skin even darker. Perhaps by putting on blackface, he was, in a way controlling minstrelsy and taking ownership of its racial representations. Through their performances, the pair crafted their own claims to racial identity and black culture while also creating quality content that would circulate Tin Pan Alley at a wide audience. Through their efforts, the pair helped audiences recognize negro talent that carved pathways with lasting effects. In 1940 for example, Duke Ellington recorded “A Portrait of Bert Williams” as a tribute. With minstrelsy’s dark beginnings, William and Walker saw an opportunity to change the way audiences thought about race and entertainment that has had lasting effects, making them a couple well deserved to have a blogpost written about.

1 http://www.brandonxshaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Walker_-The-Real-Coon-on-the-American-Stage.pdf

2 GILBERT, DAVID. “DO ALL WE COULD TO GET WHAT WE FELT BELONGED TO US BY THE LAWS OF NATURE: Selling Real Negro Melodies and Marketing Authentic Black Rhythms.” In The Product of Our Souls: Ragtime, Race, and the Birth of the Manhattan Musical Marketplace, 58-61. University of North Carolina Press, 2015. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9781469622705_gilbert.