When racial ambiguity was built into the performative framework of blackface minstrelsy, what did it mean for the audience? The racial make-up of audiences is extremely difficult to track down, particularly when it comes to performances of blackface minstrelsy in the Industrial North. One way to accomplish this is to research the race of the owner of the venue but that identity could mean nothing. Another way to learn more about audience is by reading critical reviews of blackface performance, or to examine advertisements for those performances.

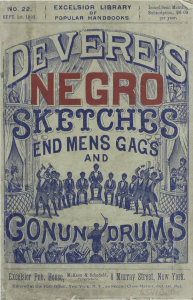

One such advertisement is an 1889 flyer for “DeVere’s Negro Sketches, End Men’s Gags and Conundrums”1 featuring an ensemble seated on stage in blackface, with white on-lookers placed above the stage in fancy clothing. This artistic framing places a white observer at the forefront of the musical space, imposing a clear hierarchy between performer and audience member.

Why does audience matter? Eric Lott writes in Love and Theft that “Regarding even the class-bound audiences of the 1840’s, there was some confusion among commentators about just who was out there in the pit and the gallery. As I will argue later, one of minstrelsy’s functions was precisely to bring various class fractions into contact with one another, to mediate their relations, and finally to aid in the construction of class identities over the bodies of black people (67).”2 Lott makes the important point that minstrelsy wasn’t exclusively white and black performers acting out racist and harmful stereotypes for exclusively white audiences, it was more complex than that.

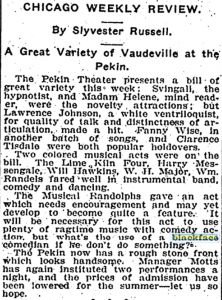

In a Chicago Weekly Review from 19113, The Pekin Theater put on several acts, including a white ventriloquist, two “colored musical acts” and a blackface ensemble. Slyvester Russell4 writes in his vaudeville review “The Musical Randolphs gave an act which needs encouragement and may yet develop to become quite a feature. It will be necessary for this act to plenty of ragtime music with comedy action, but what’s the use of a blackface comedian if he doesn’t do something?” This is a black critic, writing for a black newspaper and therefore a predominantly black audience, attending a theatre which was programming lots of types of performances all within the same week.

The audience therefore appears to be a fraught racial space, where the ambiguity and complicated racial politics being played out onstage were being echoed in the audience. In order to understand the popularity of minstrelsy, particularly as it was marketed and cultivated across geographic and cultural barriers it is crucial to consider the sheer magnitude of the audiences and to consider how it permeated and part of that research begins with combing through the legacy of performance space, not exclusively programming.

4Sampson, Henry T. Blacks in Blackface: A Sourcebook on Early Black Musical Shows. Scarecrow Press, 2013.