https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f8PXvqYpGCM

The writers for Saturday Night Live are not the first people to use African American English (AAE) and its mannerisms as comedic subject matter. AAE is defined by Mufwene in Encyclopædia Britannica as:

“a language variety that has also been identified at different times in dialectology and literary studies as Black English, black dialect, and Negro (nonstandard) English”[1]

He then goes on to explain that there is no clear consensus of how this language variety emerged. Some connect it to influences by African language, for instance as a descendant from 17th-century West African Pidgin English or, while others argue that it is an English dialect with its roots in colonial English or creole language.

Pullum stresses in his chapter in The Workings of Language[2], that what is known as the “African American Vernacular English” (AAVE), often used synonymous with Ebonics and AAE, is in fact not just standard English spoken inadequately, but is its own legitimate version. The starting point for his discussion he writes about the “media frenzy”[3] that occurred in 1996 when an Oakland School Board recognised AAVE as a language in their district due to a large Afro American Population. The critics viewed AAVE as “black slang” and not appropriate in a formal setting. Pullum argues due to the use of “a different grammar, clearly and sharply distinguished from Standard English”[4], through his linguistic analysis, this argument does not hold up.

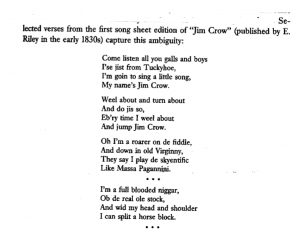

Eric Lott in his book Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class references the song “Jim Crow”[5]. The lyrics clearly reflecting, or at least trying to reflect, a specific way of speaking. What the text does not reflect, is the tone, body language and gestures that comes with any living language.

I am no linguist, but it seems to me that the major differences between Standard English are really in the spelling (or pronunciation) of a handful of words, for example “Ob de real ole stock”, not in the actual grammar. Having in mind that this text and Pullums analysis is separated by almost 170 years, which leaves room for considerable development of any language, I would be inclined to suggest that the lyrics are based of the idea, still present in 1996, that AAE/AAVE is just an inferior shadow of “proper” English.

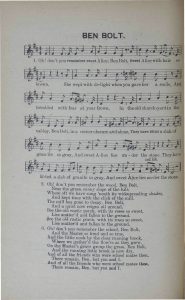

Based on the sheet music presented in How to put on a minstrel show from 1921[6], I would seem like in 100 years the language in lyrics have moved more towards Standard English. This is also present in the jokes, dialogues and monologues in the book. The author Geoffrey K. Pullum states in the beginning that his book is based of more than 30 years of experience of staging amateur minstrel shows. I will not try to pass this off as representative of the actual practice, this might just be the procedure when notating minstrel songs, leaving the interpretation to the performers. Considering this, the book is intended for amateur performers with limited experience.

Excample from How to put on a minstrel show(1921):

Saturday Night Live’s sketch reflects the portrayal of African American English previously presented in the early minstrel shows. The language and cultural non-verbal mannerisms have been made fun of, on basis of its perceived inadequacies, which in later years, have been argued are actually structural idiosyncrasies of a legitimate variety of the English language.

Primary Sources

“This is how I talk – SNL” (May 17,2015). Saturday Night Live (YouTube) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f8PXvqYpGCM [Accessed October 2nd, 2019]

Rossiter, Harold. How to put on a minstrel show. (1921) https://infoweb.newsbank.com/iw-search/we/Evans/?p_product=EAIX&p_theme=eai&p_nbid=X49Q51NGMTU3MDAyNjc0MC43NjUxMDI6MToxNDoxOTkuOTEuMTgwLjE1Mw&p_action=doc&p_queryname=4&p_docref=v2:13D59FCC0F7F54B8@EAIX-154E9B0050389E50@S1879-1606D6244F711ECF@56 [Accessed October 2nd , 2019]

Secondary sources

Pullum, Geoffrey K. “African American Vernacular is Not Standard English with Mistakes”, The Workings of Language. (1999). Westport CT: Praeger. https://web.stanford.edu/~zwicky/aave-is-not-se-with-mistakes.pdf [Accessed October 2nd, 2019]

Mufwene, Salikoko Sangol. Encyclopædia Britannica. “African American English” (January 29th 2016). https://www.britannica.com/topic/African-American-English [accessed October 1st 2019]

Lott, Eric. Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class. (1993). Oxford University Press, New York

[1] Mufwene 2016

[2] Pullum 1999

[3] Ibid p. 39

[4] Ibid p. 57

[5] Lott 1993: p. 23

[6] Rossiter 1921: p. 54