The legacies of minstrelsy touch many corners of popular culture today (for examples of these legacies, scroll through other blog posts on this page), but even when it was the country’s primary means of entertainment, its reach stretched further than one would reasonably expect. The sobering reality is that it was enjoyed by members of all demographics of American culture–including African Americans.

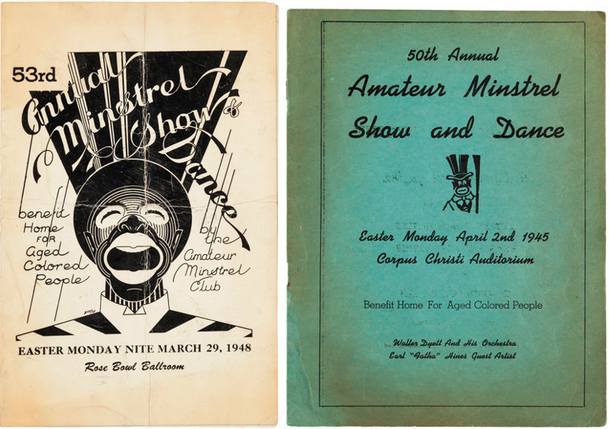

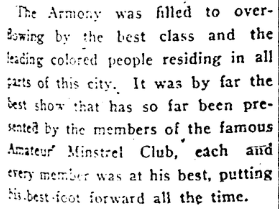

In 1924, near the end of minstrelsy’s reign as a cultural juggernaut, The Broad Ax published an article glowing with praise for the “Amateur Minstrel Club” of Chicago. Known for its founder and editor, Julius Taylor, the paper advocated tolerance and equality and occasionally featured inflammatory language.1 Most relevant to my argument, it was catered to black readers. The writer extended praise toward every component of a performance by the aforementioned club, from its “soul-inspiring” music to its “peppy” jokes and “real fun makers [sic].”2

It is hard enough to swallow the reality of minstrelsy with regard to white audiences. That a black newspaper could describe minstrel acts as “twenty times better than . . . regular traveling old time minstrel shows,” with an audience comprising “the best class and the leading colored people residing in all parts of the city” which were led to “forget their aches, pains, troubles, sorrows and suffering in this world,” is a sobering reality. But this last quote should not be too quickly cast aside; while sorrows exist for everyone, it could easily be that the paper intended to affirm the struggles African Americans were facing to change institutions and bring about the equality Julius Taylor sought. If true, this lends the reader a glimpse into a complex reality of racial politics of the time.

Assuming African American participation in the club, it seems to me that this particular group was making a bid to control black identity through commercialization. Given the support of this paper, it is unlikely it perpetuated as many harmful stereotypes as other minstrel acts. Significantly, the benefits from the performance–some $3000 dollars, worth well over ten times that much in today’s money3–were donated to a place called the Old Folks Home. This commercial success, coupled with generosity, would neatly fit into a story which shifted societal ideas about African Americans away from poverty toward ability. Even if this was a case of ceding one’s dignity in the name of making a living, their philanthropic act, coupled with the Broad Ax’s praise of the artistic skill of the performers, does foster respect for the troupe–and African Americans by extension.

While the popularity of blackface minstrelsy was and is a disturbing reality, African Americans have found ways to claim this popularity to succeed financially. More than that, and on a much more optimistic note, the stories constructed about minstrelsy by African Americans can re-frame otherwise disturbing performance to also include ability, rather than mere comedy.

1 “About The broad ax.” Library of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84024055/

2 1924. “Easter Monday Evening the Amateur Minstrel Club Gave Its Twenty-Eighth Annual Minstrel and Dance.” Broad Ax. Infoweb.newsbank.com

3 “Consumer Price Index.” Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/cpi/