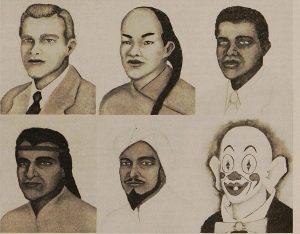

Carl Cass was a professor at the University of Oklahoma School of Drama, and wrote a newspaper article titled “Racial and Conventional Types of Make-up” in 1949.

He begins the article by dividing all races and ethnicities into the following categories: The Yellow Race, The Negro, The American Indian, The Brown Race, The Clown, and The Minstrel.

He describes the physical characteristics and facial features that he believes accompany each race, and offers instructions on how to apply makeup to most resemble this race.

Cass distinguishes between “The Negro” and “The Minstrel,” stating,”Many amateurs tend to confuse the coloring of a negro with that of a minstrel that is really a clown-caricature of a negro” (1). According to Cass, manufacturers sold shades of makeup labeled “light negro” and “mulatto,” which are much lighter in color compared to “minstrel black.”

In addition, he includes a blurb for each race describing their typical facial features. For the minstrel, Cass articulates,

“The lips tend to be thick and protruding. They may be painted as wide as desired, and, occasionally, they may be made to protrude by inserting soft rubber or chewing gum under them…Color a wide strip around the mouth for the lips with either white or very pale flesh-colored grease paint – red is a very inferior color because it lacks contrast with black” (1).

It is interesting how blackface performers placed such an emphasis on the white strip around their lips; perhaps they wanted to ensure that the audience knew they were actually white.

As one of the article’s ‘lessons,’ Cass instructs readers to “Select from papers and magazines pictures of both men and women of all races and nationalities…Classify these pictures and study them” (1).

The author of this article was a professor of drama at the University of Oklahoma, which indicates that minstrel shows were popular with both the general public and college students, and colleges were instructing students in the ‘art’ of minstrelsy.

This advertisement for the National Thespians lists its 1934-5 season “Banner Plays,” described as including “hits for schools, colleges, universities…and all other drama groups.” Enrollment in The National Thespians was open to students with extensive theater experience. Several of these shows include minstrel acts.

The fact that minstrel shows were performed in schools raises the question of intent, and how these shows infiltrated academia.

Stephen Johnson also poses this question of intent in his book Burnt Cork; he states:

There are questions of intent: whether blackface performance was integrationist, working class, and populist, parodying and complaining about those in power…or whether it was segregationist and derogatory, reinforcing a white status quo of superiority…or both” (3).

In the case of minstrel performance in schools, the intent was seemingly the latter. Drama teachers taught minstrel makeup application alongside instruction in how to dress like a clown, or how to tailor choice in makeup for the stage. From my interpretation, minstrel shows in schools were simply a part of the standard curriculum, enforcing white supremacy whether the students and professors necessarily realized it or not.

- Cass, C. B. (1949, 05). Racial and conventional types of make-up. Dramatics, 20, 6-8. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/1929314848?accountid=351

- Advertisement: BANNER PLAY BUREAU, INC. (1934, Oct 01). The High School Thespian, 6, 0-0_2. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/1929344020?accountid=351

- JOHNSON, S. (Ed.). (2012). Burnt Cork: Traditions and Legacies of Blackface Minstrelsy. University of Massachusetts Press. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5vk2wm