It’s hard to definitely say someone should not sing certain music. When it comes to spirituals, we wonder if the music was supposed to be passed down the generations, or if it was supposed to be left behind, where it could only be associated with slavery and sorrow.

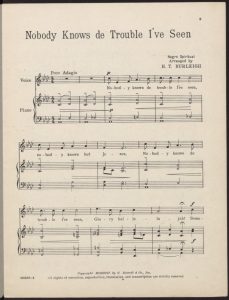

H.T. Burleigh thought such music should be remembered, as he is famous for having arranged the music for many spirituals, including “Nobody Knows de Trouble I’ve Seen”. Burleigh and others published a variety of other arrangements for “mixed chorus, men’s chorus, and women’s chorus”.1

Therefore, it is clear he intended these songs to be sung by a variety of people for generations to come. He believed that spirituals have worth to anyone and everyone. He even made a statement on the second page of this sheet music, warning not to sing these songs as if a “minstrel” performance, mocking the mannerisms of African Americans while singing the song, but instead to respect the value of such musical works:

“Their worth is weakened unless they are done impressively, for through all these songs there breathes a hope, a faith in the ultimate justice and brotherhood of man. The cadences of sorrow invariably turn to joy, and the message is ever manifest that eventually deliverance from all that hinders and oppresses the soul will come, and man–every man–will be free.”2

If a choir of white people gave a lively and vigorous performance of this spiritual or any kind like it, it would come across as disrespectful. Slaves were not allowed to sing work songs mournfully, even though the songs were of sorrow and of trouble.3 “Douglass observed in the 1845 edition of his autobiography that slaves sang most when they were unhappy”.4 A smiley performance of such music seems inappropriate. People today cannot properly fathom the hardships that slaves endured back then, so for anyone other than slaves to sing these songs does not feel right. However, Burleigh might argue that spirituals transcend the history. The music can mean a lot to a lot of people, even if for different reasons.

Perhaps it would help to imagine slaves’ reactions to performances of their songs today. They could think it beautiful that their music has survived so long and that their time is not forgotten or brushed aside as insignificant in history. However, their reaction would probably depend on what performances they see–whose singing for whom and for what reason. They could definitely find it disturbing that their music is occasionally sung out of context for the pleasure of white people listening. But what would they think if they saw a choir in Taiwan singing one of their songs?

We can’t know for sure what they would think, but perhaps if the music is performed in a respectful manner, it can mean more for more people.

1 “H. T. Burleigh (1866-1949).” Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200035730.

2 Burleigh, H.T. Nobody knows de trouble I’ve seen. New York: G. Ricordi & Co., Inc., 1917. Retrieved from Sheet Music Consortium, http://digitalcollections.baylor.edu/cdm/ref/collection/fa-spnc/id/23714.

3 Eileen Southern, The Music of Black Americans: A History (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1971), 161.

4 Eileen Southern, The Music of Black Americans: A History (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1971), 177.