Alan Lomax was a groundbreaking music collector who recorded and preserved underrepresented music, highlighting the differences between white and black musical styles in the South.

In this sense, Lomax is an improvement from scholars such as Neil Rosenberg, who wrote an extensive history of bluegrass music with little mention of race.[1] Though this type of erasure is not present in Lomax’s collection, some of his processes are nonetheless problematic. He seemed to genuinely believe that African American musical culture should be understood, yet he often requested specific songs because it fit the stereotypical idea of black folk music. He also wanted to find a sound not influenced by white folk music, and sought out black singers who didn’t spent time around white musicians.[2] This creates problems of authenticity because it neglects the fact that white and black musicians did listen to and play off one another.

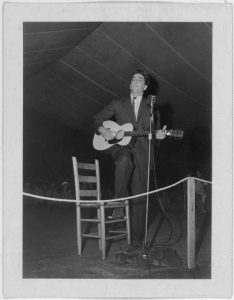

This begs the question: Was any of Alan Lomax’s revolutionary work truly authentic? I would argue that, though undoubtedly problematic, parts of it were. Vera Hall, an African American folk singer from Alabama, is a prime example of this. Many of her performances can be found in the full collection from Lomax’s 1939 recording trip. One example attached here is her recording of Awful Death, which reflects her powerful voice and the spiritual weight behind her songs.

Lomax thought highly of her talents and remarked that her voice was one of the best. Hall learned to sing traditional spirituals from her mother, but despite her talent, never became a professional singer.[3] Because of Lomax persistence, though, many of her songs are widely accessible, and she eventually gained national acclaim. “Another Man Done Gone,” one of Hall’s most famous songs, has been covered and modified by countless performers, including Johnny Cash and the Carolina Chocolate Drops.[4] In 2005, Hall was inducted into the Alabama Women’s Hall of Fame.[5] These accomplishments are no small feat for a low-income black woman in 19th century Alabama.

On the one hand, Hall’s success was significantly limited by her gender, class, and race. We would be settling for unfair societal systems by praising Lomax for introducing her voice despite the scarcity of African American musicians receiving recognition at that time. She was still branded as a black folk singer in a way that benefitted Lomax professionally, and she might not have garnered his attention had it not profited him. On the other hand, though, it might be fair to say that, by recording Hall in her environment and allowing her some agency in song selection, Lomax respectfully represented her. There are obviously countless problems with such an expansive project, and it’s likely not as authentic as Lomax would like to think. But, we can take comfort knowing that not all his work was flawed, and his introduction of Vera Hall to a larger national audience, at the very least, provided moving recordings of African American folk music.

[1] Rosenberg, Neil V. Bluegrass: A History. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2005.

[2] Paul, Richard. “In the Field of Folk Music, Alan Lomax is a Giant – If a Flawed and Controversial One.” Public Radio International. February 10, 2015. Retrieved from https://www.pri.org/stories/2015-02-10/field-folk-music-alan-lomax-giant-if-flawed-and-controversial-one.

[3] Vera Hall -1964. Online Text. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200196840/. (Accessed February 26, 2018.)

[4] Wade, Stephen, and Stephen Wade. “Vera Hall: The Life That We Live.” In The Beautiful Music All Around Us: Field Recordings and the American Experience, 153-78. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2015.

[5] Stone, Peter. “Vera Ward Hall (1902-1964).” Association for Cultural Equity. Retrieved from http://www.culturalequity.org/alanlomax/ce_alanlomax_profile_hall.php