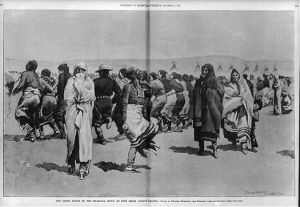

Historically, most Americans lack a thorough appreciation of Native American culture. One way we can begin to understand this rich culture is through a study of Native American music, which often closely relates to culture and religion. One example is the Ghost Dance, a religious ceremony in which tribal members sing and dance on four consecutive nights. The songs include repeated chants (usually an a-a-b-b phrase) while members of the tribe dance enthusiastically in a circle. Included here is an example of a Ghost Dance song from a tribe in the western Great Plains. It was recorded as part of James Mooney’s recordings of American Indian Ghost Dance Songs in 1894.

Although specifics rituals and song patterns differ depending on the region or tribe, each Ghost Dance represents an intensely cultural experience during which “communal performance of song and dance” is the center piece of [the] religion” (Vander 113).

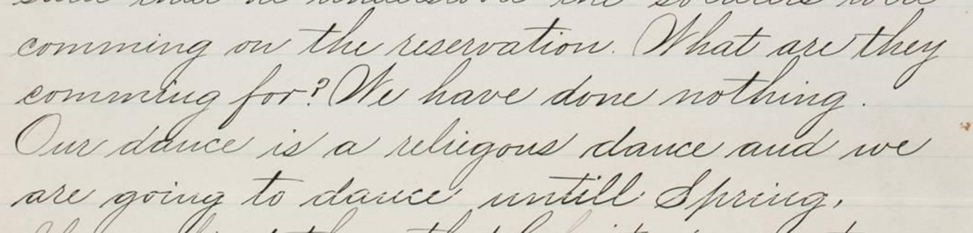

We now know and understand the elements of this dance, but there were (and still are) gross misconceptions about the meaning of the Ghost Dance. One letter from the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota highlights this lack of appreciation for Native American culture. The letter, written in 1890, by John M. Sweeney, a white schoolteacher, is addressed to a U.S. Indian responsible for implementing federal policies on reservations. Sweeney echoes Chief Little Wound’s sentiments that the Ghost Dance is not a threat, and that U.S. troops are encroaching on the reservation with no justification. His letter asserts that the Dance will continue until Spring no matter the consequences.

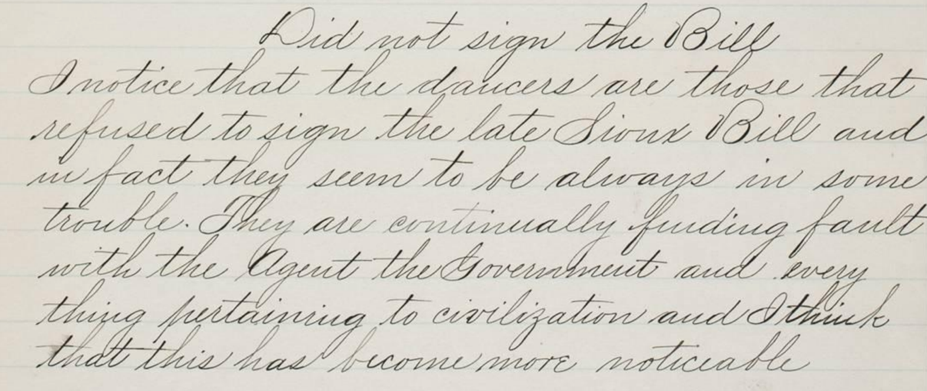

At first, it appears that Sweeney is sympathetic towards the Native Americans, yet he later comments on the stubbornness of those who continue to dance. He notes that those who lead the ceremony are also those who refused to sign the Sioux Bill, a government-forced bill that reduced Sioux Reservation land mass, broke up tribes, and placed further restrictions on Native American groups (North Dakota Studies).

In fact, Sweeney speculates that this Ghost Dance was indicative of the Native Americans’ plan to revolt. He shows a blatant disregard for Native American culture. It acts as a real-life example of how tensions plagued relationships between the Native Americans and European immigrants. U.S. government fear that the Ghost Dance in 1890 was a threat led to the Battle at Wounded Knee, where approximately 300 Native Americans were murdered. This widespread misunderstanding ultimately carried forward through the recording of U.S. history.

The Ghost dance by the Ogallala Sioux at Pine Ridge Agency … Dakota / Frederic Remington, Pine Ridge, S. Dak.

Through the Ghost Dance, Native Americans connected to nature with expressive song and dance, hopeful that their spirits would restore prosperity and the Indian way of life. Historians now understand the cultural importance of musical ceremonies like the Ghost Dance. There is much to glean from this culture that can, hopefully, create a new understanding of ways in which historical biases have caused harm, and restore an appreciation for the rich culture of Native American peoples.

Sources:

“Breakup of the Great Sioux Reservation.” North Dakota Studies, State Historical Society of North Dakota, www.ndstudies.gov/content/breakup-great-sioux-reservation.

Browner, Tara, ed. Music of the First Nations: Tradition and Innovation in Native North America. University of Illinois Press, 2010.

Mooney, James, and Smithsonian Institution. Bureau of Ethnology. James Mooney Recordings of American Indian Ghost Dance Songs. [Washington, D.C.: E. Berliner, 1894] Audio. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2014655251/>.

Remington, Frederic, Artist. The Ghost dance by the Ogallala sic Sioux at Pine Ridge Agency … Dakota / Frederic Remington, Pine Ridge, S. Dak. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/90707734/>. 1890.

Sweeney, John M, Author. Letter and List [Manuscript]. Correspondence. Retrieved from America Indian Histories and Cultures, http://www.aihc.amdigital.co.uk/Documents/SearchDetails/Ayer_MS_3176?SessionExpired=True. 1890.

Great post! I particularly appreciated the historical recording – isn’t the Library of Congress great??? One interesting thing about that recording is that it seems to involve someone sitting in front of a recording device, meaning the song was divorced from its context to facilitate recording. (If this is a “dance,” we should be able to hear dancers, and probably other singing.) That alone shows that collectors were interested in preserving some things about American Indian music, but weren’t interested in holistic, respectful preservation in the same way that ethnomusicologists today are.

Your writing is great and your primary sources are fascinating. If I were to push you to improve something, it would be in making explicit connections to the readings. You could mention how Desnmore fits in, or compare the collection and criticism that took place in primary sources you found with what you read in Dan Blim’s or Bruno Nettl’s essays. Clearly you’ve internalized class discussion, but readers will be impressed if they see you engaging with scholarship (like Browner’s – excellent source!) within your prose.

Keep up the great work!