When considering the rise of concert music in America, scholarship often directs its attention to the founding of the New York Philharmonic Society in 1842 as landmark in Americans coming together for orchestral symphonic concert music. According to Crawford, the ensemble was founded as a “cooperative venture whose playing members were less interested in financial gain than in the chance to play the best symphonic music.”1 The ensemble only played four concerts in the first year, however Crawford points to its survival as proof that it “filled a need on the local scene.”2

“Theodore Thomas” New York Philharmonic Biographies https://nyphil.org/about-us/artists/theodore-thomas

However, I do not think it is fair to focus only on the Philharmonic as the sole introduction of symphonic concert music to popular American taste. Another factor to consider is Mr. Theodore Thomas and his influence on the genre. Thomas started out playing in the first violin section of the New York Philharmonic Society before moving to a conductor position with the Brooklyn Philharmonic Society.3 During his time at the Brooklyn Philharmonic, Thomas “evolved a formula to please the public and yet challenge, educate and uplift it” through the programming of European classical music.4 Through his lens, concert music by European masters was exactly what Americans needed and deserved to hear.

Later in the 1860s, Thomas went on to develop the Theodore Thomas Orchestra as resident to the Brooklyn Society and also to travel on tour along what was deemed the “Thomas Highway.”5 Thomas’s motivation to tour was likely an extension of his desire to share and spread the music he loved to the people of the America. Thomas was also notable for his impresario skills which he used to not only conduct the music but also to coordinate the finances and management of his orchestras.

“Thomas viewed himself as an agent in the work of raising musical standards to secure the symphony orchestra’s place in the United States.”6

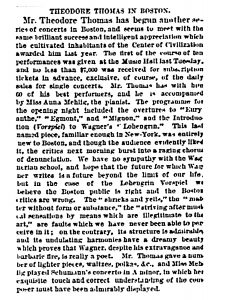

In this article from the New-York Tribune, the journalist describes the contrast between the Boston audience’s response and the critic’s opinion upon hearing a concert including “Vorspiel” from Wagner’s opera Lohengrin. “The audience evidently liked it” the writer says, but critics found issue with the inclusion of Wagner because of his political ideology.7 Ultimately though, the journalist takes sides with the audience who loved this piece for its musical quality.

In this article from the New-York Tribune, the journalist describes the contrast between the Boston audience’s response and the critic’s opinion upon hearing a concert including “Vorspiel” from Wagner’s opera Lohengrin. “The audience evidently liked it” the writer says, but critics found issue with the inclusion of Wagner because of his political ideology.7 Ultimately though, the journalist takes sides with the audience who loved this piece for its musical quality.

“Its undulating harmonies have a dreamy beauty which proves that Wagner, despite his extravagance and barbarie fire, is really a poet.”8

This brings me to my final query, which is whether or not we can count the music performed by Thomas and the orchestras he led as “American.” Even though a great majority of the music he chose to perform was written by European composers, I pose it is possible we consider it “American Music” if we use the label to describe it as an essential part of American culture. This leaves room for extensively more detailed research as to what exactly this music provided to audiences of the time as well as whether or not the rise of orchestral symphonic concert music, starting out with European classics, led to a later rise of American composers in this genre.

1 Richard Crawford, America’s Musical Life: A History, (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2001), 304.

Great work uncovering the central role of Theodore Thomas in 19th century American classical music history. You’re absolutely right that we *have* to adjust our definition of “American” music to accommodate Thomas and his orchestras because the music they performed (and therefore the musicians who performed the music) were so central to burgeoning ideas of respectability, edification, and culture in 19th-century America. Your post is also filled with rich sources and sound clips – thank you!