Throughout history, many oppressed people have not received documentation or enough accurate documentation regarding their culture and other aspects of their lives. Especially in musicology, documentation can be scarce and inaccurate. For many sources that scholars depend on, it is crucial to think critically about the presumtions and backgrounds of those who created them. However, it is also important that we preserve the resources and works that we do have. Sometimes it is better to have semi-accurate interpretations of music and culture than nothing at all. Even biased information can provide insightful information about who created it. One effective way to avoid misrepresenting people is to interview and accurately preserve their traditions.

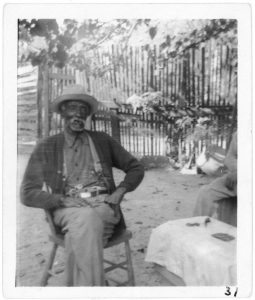

In this recorded interview with ex-slave Billy McCrea, McCrea elaborates about his experiences as a slave working on a Steamboat as a cook. Upon request, McCrea sung the steamboat song, “Blow Cornie Blow” for the interviewer John Avery Lomax.

Blow Cornie Blow

“I think I hear the captain call me, blow cornie blow.

I think I hear the captain calling, blow cornie blow.

A blow cornie blow.

Blow cornie blow.

A blew it cold, loud and mournful.

Blow cornie blow.

I think I hear the captain??? –blow cornie blow.

They carried lo-o-o-o-ong onto bend.

Blow cornie blow.

They soon will be to the landing corner.

Blow cornie blow.

De captain hand me down my ???

Blow cornie blow.

Oh, blow boy and let them hear you.

Blow cornie blow.

Oh, blow loud and ???

Blow cornie blow.

Oh, blow loud just so he can hear you.

Blow cornie blow.

I think I hear the captain call you.

Blow cornie blow.”

He explained that he and “the boys” would tote salt from the boat to a warehouse while singing. Upon hearing McCrea sing, it is tempting for scholars and students alike to want to notate “Blow Cornie Blow.” This stems from a western presupposition that written forms of preservation are more superior, accurate or long lasting than preservation through oral tradition. Is written preservation of oral tradition inherently problematic? Because scholars notated slave songs using a western notation system, they were limited because they could not capture all of the musical nuances and emotions of the slave songs. Notating slave songs is useful to provide context to people who were more familiar with European music, but what is problematic is imposing western traditions on slave songs and adapting them. Many slave songs were published with harmonies that were not originally sung. This act of “fixing” or refining slave songs to conform to a western ideal of beauty contributes to the erasure and inauthentic representation of black folk music. Many debates regarding notation must address the issues of preservation, authenticity and erasure of tradition.

Eileen Southern’s book, The Music of Black Americans: a History, recalls a quote from Frederick Douglas remembering the songs as “they were tones loud, long, and deep; they breathed the prayer and complaint of souls boiling over with bitterest anguish…The hearing of those wild notes always depressed my spirit, and filled me with ineffable sadness.”

Interviews like McCrea’s are so important regarding of preservation of history and prevention of erasure of people, or distortion of their stories. Lomax’s work positively contributes to the study of slave music because he gives voice to the people whom we draw from in music and culture.

Works Cited

Lomax, John Avery, et al. “Interview with Uncle Billy McCrea, Jasper, Texas, 1940 (Part 1 of 2).” The Library of Congress: National Jukebox, 1940, memory.loc.gov.

Southern, Eileen. “Chapter 5 Antebellum Rural Life.” The Music of Black Americans: a History, W. W. Norton & Company, 1997, pp. 177–178.