After Salome’s “Dance of the Seven Veils” hit the United States in 1907 in Strauss’s opera, an outbreak of “Salomania” occurred in which many songs and dances in the popular sphere took on a Salome theme. By 1908, vaudeville and burlesque shows were full of different Salomes, from “When Miss Patricia Salome Did Her Funny Little Oo La Palmoe” to “My Sunburned Salome” to “The Dusky Salome.” What all of these representations of Salome have in common is the fact that none of them are authentic to the opera’s portrayal of Salome and none of them try to be. The writers of such songs capitalized on inauthenticity, giving audiences exaggerated, drag-like performances of stock characters so far from reality that audiences could enjoy them.1

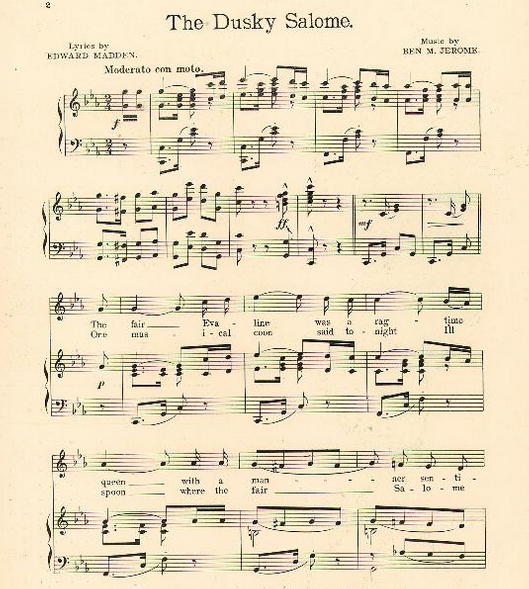

One stock character used for Salome was the white, American girl-gone-wild, and another was the overly ambitious African American woman performer.2 “The Dusky Salome” (lyrics below; listen here3) portrays the latter:

The fair Evaline was a ragtime queen

with a manner sentimental;

But she sighed for a chance at a classical dance

with a movement oriental.

When lovesick coons with ragtime tunes

sang, “Babe, you’ve got to show me,”

She’d answer, “Bill, you bet I will,

I’m going to dance Salome.

Oh, oh me, that’ll show me, For

CHORUS: [the music shifts to ragtime]

I want a coon who can spoon to the tune of Salome.

I’ll make him giggle with a brand new wiggle that’ll show me;

In a truly oriental style,

With a necklace and a dreamy smile

I’ll dance to the coon who can spoon to the tune of Salome.

One musical coon said tonight I’ll spoon

where the fair Salome lingers.

When she danced ’round the place he just covered his face

but he looked right thro’ his fingers.

He sighed “It’s grand my heart and hand

I’d give to see you do it,”

She only said: “Give me your head

I’ll dance Salome to it,”

I’ll woo it, that’ll do it. For4

“The Dusky Salome” parodies that idea that Salome could be used to bridge the gap from low art to high art and from blackness to whiteness. This idea is ironic because Salome’s dance in Strauss’s opera is not traditional high art–it contains the exoticized sexuality more typical of popular music and usually required of African American women. Ultimately, the song reinforces the idea that sexuality, foreignness, and blackness belong to low art, not high.

“The Dusky Salome” parodies that idea that Salome could be used to bridge the gap from low art to high art and from blackness to whiteness. This idea is ironic because Salome’s dance in Strauss’s opera is not traditional high art–it contains the exoticized sexuality more typical of popular music and usually required of African American women. Ultimately, the song reinforces the idea that sexuality, foreignness, and blackness belong to low art, not high.

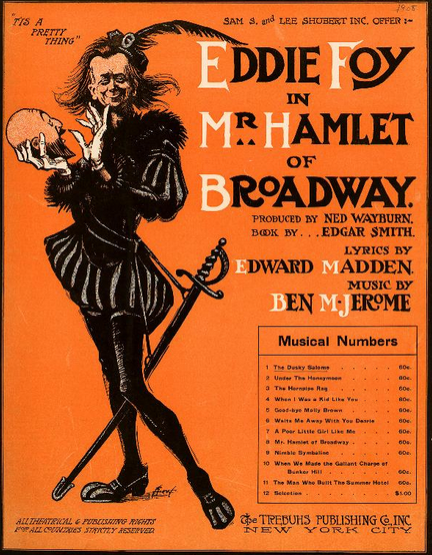

What’s more, the song’s mixing of musical genres, use of “oriental” sounding lower neighbors (m. 16), and use of stock-characters (including the pejorative c–n character popular in minstrelsy) verifies popular song as a place of cheap thrills and commodification. The cover of the sheet music for the book in which “The Dusky Salome” appears explains it all with a male actor playing Hamlet but holding the head of John the Baptist as Salome does when she kisses it. The intent of this odd melange is obviously humor based on inauthenticity, not edification, which was reserved for the classical sphere.

To conclude, songs like “The Dusky Salome” served to maintain the distinction between lowbrow music and highbrow music, perpetuating a binary system that kept sexuality and “otherness” at the bottom and edification and whiteness at the top.

Footnotes

1 Larry Hamberlin, “Visions of Salome: The Femme Fatale in American Popular Songs before 1920,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 59/3 Fall 2006, pp. 631-696.

2 Ibid.

3 Jerome, Benjamin, Edward Madden, and Maude Raymond. The Dusky Salome. Recorded August 2, 1909. Victor, 1909, Streaming Audio. Accessed April 14, 2015. http://www.loc.gov/jukebox/recordings/detail/id/1586

4 Jerome, Benjamin and Edward Madden. “The Dusky Salome.” In Eddie Foy in Mr. Hamlet of Broadway. New York: Trebuhs, 1908.

Great post, as always. I already mentioned this in class, but for posterity I thought I’d link to my very favorite Salome spin-off: Irving Berlin’s “Sadie Salome: Go Home!” from 1909. (http://sadiesalome.com/about.html?KeepThis=true) I sometimes wish that every time one of Berlin’s famous “American songbook” tunes played on the radio, they would also play one of his incredibly offensive ethnic stereotyping songs (other good ones include “Abie Sings an Irish Song” and “My Father was an Indian”).