Folk music is ingrained in a sense of community and expression of the common man that many young people of the 60s and early 70s found as representative of the times and themselves. Folk artists played simply–typically a voice and guitar, with perhaps a harmonica. Listeners could collectively identify with the simplicity, and would feel connected to their peers. Folk music conveyed a peaceful time of long hair, free love, and a bohemian lifestyle.

But underneath the easy-strumming guitar and speak-singing voices were lyrics against the establishments that folk artists were so against. In 1967 festival singer Tim Buckley’s song, “The Earth is Broken,” government figures are called thieves.

But soon love is broken, they’ll take you away

Oh the wars they been growing as no relief

And the old men who ruled them oh they’re just like thieves

They rob from the sunshine, oh the air ain’t so clean

Our rivers are dirty where once we could see

A smile from your lady friend looking down

Look at that river hey did you ever shiver

Well the earth is broken there is no one to save

The “Home on the Range” era of sunny skies and seldom-heard discouraging words is definitely over.

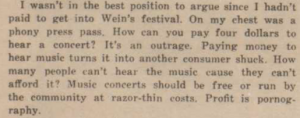

In this article from East Village underground magazine The Other, Jerry Rubin presents his account of the 1967 Newport Folk Festival. Rubin is so against the idea of paying for music that he decided to attend the festival by creating a fake press pass.

In this article from East Village underground magazine The Other, Jerry Rubin presents his account of the 1967 Newport Folk Festival. Rubin is so against the idea of paying for music that he decided to attend the festival by creating a fake press pass.  “Music concerts should be free,” he says. “Profit is pornography.” Rubin then gets himself kicked out of the festival by passing out “a copy of the free Yippie newspaper…(spiritual thoughts from our anarchist-revolutionary point of view)” to a pair of nuns. The magazines are deemed to have pornographic images themselves, and the festival cops escort Rubin out, Rubin blaming it on his hippie appearance.

“Music concerts should be free,” he says. “Profit is pornography.” Rubin then gets himself kicked out of the festival by passing out “a copy of the free Yippie newspaper…(spiritual thoughts from our anarchist-revolutionary point of view)” to a pair of nuns. The magazines are deemed to have pornographic images themselves, and the festival cops escort Rubin out, Rubin blaming it on his hippie appearance.

What this account illustrates is the atmosphere of festivals like the Newport Folk Festival. They were attended by a variety of groups, but all came to experience the community spirit so often found in folk. In unity, concert attendees were able to band together and share ideas. In addition, the values of folk music are passed to the people. While folk music quietly discusses political issues, listeners took these complaints to heart and acted out against the closest representation of the establishment–in Rubin’s case, the festival security. The sense of community gave a feeling of strength to festival-goers which was heavily expressed in their actions.

While folk music is overall peaceful, its political undertones were strong enough to convince listeners to act out upon the messages they heard. Political events of the time period combined with the inclusive underground communities created an acceptable atmosphere of dissent and resistance.

Sources:

Rubin, Jerry. “Yippie go home!” East Village Other, Vol.3, no.3. December 15, 1967. Accessed from Popular Culture in Britain and America, 1950–1975.

http://www.rockandroll.amdigital.co.uk/Contents/ImageViewer.aspx?imageid=1099190&searchmode=true&hit=first&pi=1&themeF=Civil+Rights+And+Race+Relations%7cMusic&vpath=searchresults&prevPos=1065501

Great topic and great primary source discovery, S! We often forget that there is more to folk music (namely, disillusionment and frustration) than nostalgia and good feelings. I am particularly interested in what you are framing as anti-establishment tendencies, as it displays a common thread in some of the most significant folk and pop music in 20th century United States. I also wonder if this perception of ‘profit as pornography’ regarding music only applies to folk, as opposed to ‘art music’.