Although the America of the Pre-Civil War Era presented racial discrimination and bias in most career paths, music was one of the few platforms in which both white and black musicians could successfully perform. Francis “Frank” Johnson (1792-1844) was among one of these musicians. As a composer, bandleader, and trumpeter, Johnson possessed a diverse range of musical talents and ability which he drew upon for his concerts. His musicians were also multi-talented and would often switch instruments halfway through their concerts.

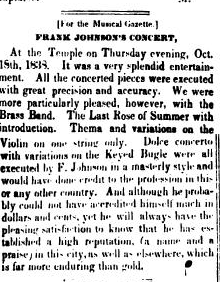

This brief concert review from the Boston Musical Gazette on Oct 31, 1838 gives an insight into the positive reception that Frank Johnson and his band received after their performances. The song mentioned in the review, The Last Rose of Summer is based off of a poem by Thomas Moore. Though nearly 70 years later, this recording of soprano Elizabeth Wheeler from 1909 is the same basic melody that was performed at Johnson’s concert.

The Keyed Bugle referenced in the performance was a recent instrument introduced around 1810 but fading out before the end of the civil war in 1850. An illustration of the Keyed Bugle can be found in the 1941 book Soldiers of the American Army, 1775-1941, by Frederick Todd.

Jeff Stockham of the Federal City Brass gives a brief history and demonstration of what the Keyed Bugle sounds like on YouTube:

The Boston Musical Gazette’s article is enlightening as a more detailed description of the type of music and instrumentation may have been used at Francis “Frank” Johnson’s concerts. Particularly with Pre-Civil War music and musicians, it is difficult to discover detailed accounts due to the lack of recordings from this time. This means that a heavier reliance must be placed on written newspaper reviews or eyewitness accounts. In this particular instance, some valuable information can be gathered simply from the short paragraph found in the Boston Musical Gazette: the positive reception of the concert by the audience, a title of one of the pieces performed, and a reference to one of the unique contemporary instruments used.

![[Francis Johnson.]](http://images.nypl.org/index.php?id=1257971&t=r)

Great work, C! I’m glad you picked up on this thread, which we didn’t have time to talk about in class. Clearly we have to be careful not to reduce African-American music making in the pre-Civil War years to slave songs or religious worship, since there were a number of professional musicians plying their trade in the cities as well. Eileen Southern and Dena Epstein both include accounts of black musician families and successful individual performers in their books, so if you’re interested in pursuing this further, those might be good places to start.

Do me a favor, and link where you can to the sources where you found your article and the image from “Soldiers of the American Army.” In the first case, we want to share with others the awesome primary source collections at St. Olaf; in the second case (assuming you got it from the NYPL) we want to share all the great, freely-available collections out there. It should be possible to link from the image itself, so that if someone clicks on it they’re taken to the original source.

Speaking of those sources, the images and audio you found are fascinating. Where did the portrait of Johnson come from? I wonder how common it was for a black musician to have his portrait done in the early 19th century – it seems pretty remarkable. Also interesting is the soldier holding the bass bugle (aka Ophicleide, as the marginal comment at the bottom of the page points out). The “Corps d’Afrique” were the black units formed in Louisiana during the Civil War. It makes sense that they would have had their own regimental bands, but what did they play, and who were the musicians who played? Now *that’s* a research topic!