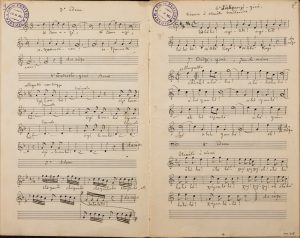

Father Émile Pentitot was a French missionary who spent years of the late 19th century in the Canadian Northwest with the goal of spreading religion, collecting data on native tribes, and mapping and recording ethnic and geographic data.1 Petitot published many of his findings, with his most famous being the “Dictionnaire de la langue dènè-dindjié,” which was a book of definitions and translations of the major Athabaskan languages.1 His research shown below is a collection of Native American music, titled “Chants indiens du Canada Nord-Ouest,” collected between the years 1862-1882.

This source is quite unique to Petitot’s works, seeing as he is primarily a geographer and linguist, which raises the question: why did he collect this source? He had no motivation from the government as Francis Densmore would almost 10 years later and he wasn’t a musicologist. While Petitot was primarily a missionary, he also had a personal mission of collecting as many geographical and ethnographic observations about the region as possible.3 This includes music, especially that of community gatherings. Petitot also saw language as the key to religious conversion,3 which also applies to music. Petitot could have seen music as another opportunity to relate the music of the church to tribal song, and create a sense of familiarity between them. Lastly, Petitot was himself an appreciator of the arts,1 and could be intrigued by collecting the music that he observed alongside his drawings of Athabaskan settlements and clothing.

Is this source an representation of the Athabaskan cultures? It is unlikely. As observed with Densmore and other white researchers aiming to document Native American music, this music is not meant to be written in Western notation, or the notation that is often seen throughout America and Europe today. There is a loss of nuance in rhythm, pitch, vocal tone, and energy. For example, in the source above, Petitot uses a standard five line staff and treble clef to notate these songs. He uses meters such as 3/4 and 6/8 and musical terms such as “da càpo” and “risoluto” to describe the music.4 None of these terms are ones which the Athabaskan tribes would understand or used to describe their music themselves. Further, the music was most likely not consensually taken from the culture which it originated. This is further evident by the fact that Petitot was a missionary,1 whose whole job is to convert others to their religion. He also made many incorrect assumptions about the tribes that he visited due to long-standing mental confusion, including a belief that there was a world-wide conspiracy to murder him in order to prevent continued research.3 He was also not a good person in general, being excommunicated from his mission group in 1866 due to a sexual relationship with a boy servant.2

Overall, while this source is an intriguing look into historical research and collection of Athabaskan culture, it is most likely not the most accurate representation of their culture, and is most likely intrusive and assumptive of their practices.

1 Savoie, Donat. 1982. EMILE PETITOT (1838-1916). Arctic, vol. 35, no. 3,, pp. 446–47. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40509367. (Accessed 19 Sept. 2024).

2 John S. Moir. “PETITOT, ÉMILE (Émile-Fortuné) (Émile-Fortuné-Stanislas-Joseph),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/petitot_emile_14E.html. (Accessed September 19, 2024).

3 Honigmann, John J. “EMILE FORTUNÉ STANISLAS JOSEPH PETITOT ENCYCLOPEDIA ARCTICA 15: BIOGRAPHIES.” Dartmouth College Library, collections.dartmouth.edu/arctica-beta/html/EA15-56.html. (Accessed 19 Sept. 2024).

4 Petitot, Father, Emile. “CHANTS INDIENS DU CANADA NORD-OUEST [MANUSCRIPT]: RECUEILLIS, CLASSÉS ET NOTÉS PAR EMILE PETITOT, PRÊTRE MISSIONNAIRE AU MACKENZIE, DE 1862-1882, 1889.” Mareuil-lès-Meaux (Seine-et-Marne), France. (Accessed 19 Sept. 2024).

Abby, this is a terrific look into this figure and his problematic approach to Native American music. You provide a nice summary of the myriad complications that emerge from these sources. Certainly, Pentitot’s approach reflects the concerns of many late 19th c. “ethnologists” whose concerns were largely aesthetic, rather than cultural.

The formatting on this post is excellent, with one exception: make sure you provide working links to the resources you discuss. The goal is to help your reader retrace your research in as few steps as possible.