Francis “Frank” Johnson was a distinctive figure in U.S. music history, not only because of his many achievements and musical innovations, but also in his unique sociocultural position in the antebellum world. His accomplishments were fascinating, including being the first U.S. musician to tour Europe and to lead an interracial musical performance, alongside a multitude of compositional innovations—some of which are believed to have inspired other composers of and since his time.1

However, Johnson’s concurrent involvement in white, upper-class spaces and various Black churches—as well as records exhibiting pro-Black ideals—suggest a rather dichotomous placement and standing in society and politics. While Johnson mostly avoided minstrel songs/shows—with the exception of “Miss Lucy Long” and “Sam of Tennessee and Dandy Jim of Caroline”—he primarily composed and performed patriotic band music and within European classical genres.2,3 Albeit, secondary source note that Johnson only performed “Miss Lucy Long” in England to appease the British upper-class, and “refused to cater to racism” by never performing the piece for Philadelphia.4 Even though Philadelphia was a rather progressive city with an Abolitionist society compared to the rest of the country at the time, incidents of hate, mockery, and racism were still present.5 It almost seemed as if he was living a double life, hidden between the pages of long-forgotten history periodicals—and I became deeply invested in trying to uncover whatever meager clues I could manage to find.

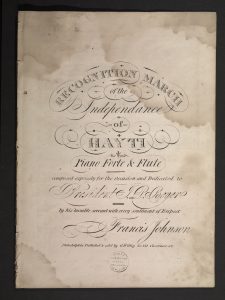

Johnson, Francis. “Recognition March of the Independence of Hayti : For the Piano Forte & Flute.” Philadelphia: G. Willig, 1826. Colenda Digital Repository.

Kramer, Hayden James. “Six Works by Francis Johnson (1792–1844): A Snapshot of Early American Social Life.” ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2022. 143-148.

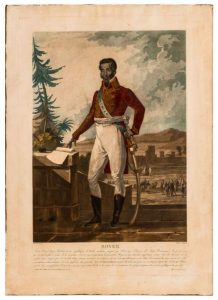

I was particularly drawn to his pieces “Recognition March of the Independence of Hayti” and “The Grave of a Slave” (pictured above), and what they could reveal about Johnson’s complicated relationship with white audiences and society. The lyrics of Johnson’s “The Grave of a Slave” were set to an abolitionist poem by Sarah Louisa Forten, openly admonished slavery and slave-owners in the text, and was formally published in Philadelphia. His “Recognition March of the Independence of Hayti” was arranged for piano and flute, but still carried similar abolitionist indications and was dedicated to one of the leader’s of the Haitian Revolution, President Jean-Pierre Boyer. Upon visiting his house, one of Johnson’s violin students also recorded that Johnson had President Boyer’s portrait hung over his mantle.6 Considering the many sociopolitical factors that could have negatively impacted the survival and coverage of such documents, these bits of Johnson’s worldview stand out to me as compelling possible evidence for his progressive beliefs.

Charon, Louis Francois. “Broadside : Jean Pierre Boyer, President de La Republique d’Haiti.” Between the Covers.