When looking at maps in our class, we’ve observed that many conclusions can be drawn from a map regarding the author’s intentions: how they want to use the map, and to what end. Advertisements are no different, and it’s important to acknowledge what an ad is attempting to achieve and how it tries to reach its goal. This furthers our understanding of the author and the context for when it was made. A clear example of this can be found in the 5th Annual American Negro Music Festival Program, held on July 8th, 1944 (1). The program functioned as a flyer to promote the event to potential ticket buyers as well as show audience members what they were in for.

From our modern-day perspective, the opening cover seems to be disarming and doesn’t give us much information about the concert itself. It’s held at the White Sox Ball Park, a relatively-large venue. The title is specific enough so viewers understand that the festival will feature some aspect of African-American music, but vague enough for viewers not to know which one. Could it be folk? Classical? Jazz? Spirituals? The front cover intentionally gives us no answer.

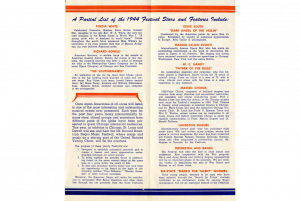

Then we move to the inside of the pamphlet, and much more is revealed. All of the main acts listed are African Americans who perform inside the European concert tradition and individuals respected in academic circles, or at least the program frames it as such. Names such as Madam Lillian Evanti and Langston Hughes are mentioned. The program also wants to make clear its goals as a social-justice event and goes out of its way to articulate its intentions “to create a keener and more appreciative understanding between all racial groups” (2).

Finally, the last page includes a final call to get tickets and endorses itself with the names of well-known political figures and organizations. Notably, the public figures mentioned are all white. Looking at all of the observations we’ve gathered, we can conclude that this was undoubtedly targeted at white audiences. Every aspect of the planned event and this advertisement appeals to white sensibilities. All of the African American artists listed are noted as excelling at white traditions of opera, poetry, composition, and European music. It makes no mention of Spirituals, Jazz, Blues, or Folk music – all genres that were spreading at a rapid pace among African American musicians. The endorsements come from white authority figures, rather than Black intellectuals and leaders at the time. Langston Hughes was involved with this event and was a prominent Black cultural leader. Why not have him endorse it? The fear was that doing so would scare white audiences away.

While the seeking of white approval is disappointing from our present-day perspective, it doesn’t undercut the concert’s historical intentions of racial justice. At the time, putting together an event at this scale that featured Black musicians and artists was highly unusual, and likely a huge risk for all financially invested parties. However, this does not permit filtering black art through a white lens, especially not in the present day. If we seek to dismantle implicit racism that events like these perpetuated, we must acknowledge the impact it had (good and bad) to avoid making the same mistakes.

(1) Evans-Tibbs collection, Anacostia Community Museum Archives, Smithsonian Institution, gift of the Estate of Thurlow E. Tibbs, Jr.

(2) Evans-Tibbs collection, Anacostia Community Museum Archives, Smithsonian Institution, gift of the Estate of Thurlow E. Tibbs, Jr.