The liner notes to Ragtime Jubilee, recorded in 1947 in New York and released in 1999, suggest that ragtime is an undying art, in much the same tone that blues musicians have suggested that the blues has always existed. While the context of the record’s quite late release date might make one immediately wary that the publishers’ desire to make money outweighs their desire to provide an accurate representation of the varied history of ragtime, considering the perspective offered is worthwhile, because it sheds light on how ragtime has been successful both as popular music and as art music.

Rudi Blesh (1899-1985), a jazz critic and enthusiast (and, notable for this class, a white man), writes about ragtime in a very positive light; it is the “warmest, gayest, liltingest music ever born here” to him, and held the greatest potential to create an American sound. He remarked that Europe immediately understood its uniqueness and vitality, and while American society forgot it for a time, it persisted until “we simply discovered what had been going on all the time.” To Blesh, ragtime was not a museum piece but a living and dynamic art form worth as much as the works of Mozart.

This suggestion, that ragtime somehow has shed its need for an audience and survives on its own, simply by being passed down from musician to musician, is both strange and familiar. It once again recalls images of the blues always existing, whether or not the public knows about it, but also images from the western classical tradition. That tradition is not part of popular culture, yet lives on as conservatories and teachers pass their practices to further generations. Some elements of classical music have permeated popular culture, such as the symphony orchestra being used in movie scores, but it has largely been relegated to a niche audience. Ragtime has since fallen from the public eye as well, but it is still passed down in some form, which I can personally attest to as a pianist.

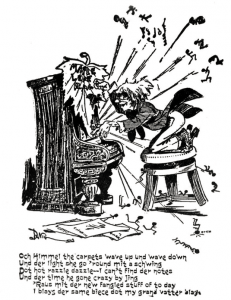

This context makes a piece of art included in the liner notes a bit ironic, as it appears to satirize the (largely German) classical tradition by implying the performer is unable to play the “new fangled stuff” that is ragtime, choosing instead to play old music that is considered to be great and timeless–not unlike how ragtime revival artists return to an earlier style when popular music has moved on to new things. There are some notable differences between genres–their respective focus on complex harmony versus complex rhythm, the varying lengths of pieces, typical orchestrations, not to mention the predominance of black composers in ragtime–potentially referred to in this record by “Jubilee,” a word which appears in famous spirituals and the names of groups which sing them. These differences aside, however, the similarities between changes in these genres’ popularity over time, as well as the continued practice and interpretation by new musicians, helps to elevate ragtime as an art form and dignified link in the evolution of American popular music.

Bibliography

“Jazz Scholar Rudi Blesh; Historian, Biographer, Critic,” Los Angeles Times (1985). https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1985-08-31-fi-24324-story.html