I would like to begin by directing your attention to the highlighted excerpts from the following newspaper article:1

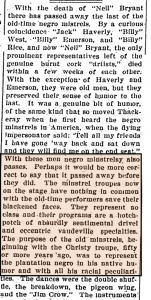

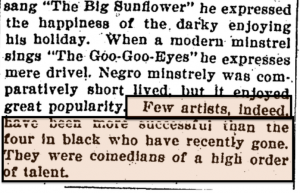

All of the writers mentioned, Jack Haverly, Billy West, Billy Rice, Billy Emerson, and Neil Bryant, were white. Somewhat surprisingly, this article was published in Oregon’s first black newspaper, the Portland New Age, in 1902. As we can see, this article mourns the deaths of five blackface minstrelsy writers of legendary status. Let’s take a closer look at the first mentioned, Jack Haverly. In 1902, the same year of the article’s publication, Haverly published a book called Negro Minstrels: A Complete Guide to Negro Minstrelsy, Containing Recitations, Jokes, Crossfires, Conundrums, Riddles, Stump Speeches, Ragtime and Sentimental Songs, etc., Including Hints on Organizing and Successfully Presenting a Performance.2 Whew! The name leaves nothing to the imagination, but in short, this book provides a template for how to create a successful minstrel show. Successful even in the minds of black audiences. So let’s take a look at what Haverly might have recommended:

As researchers who are far(ish) removed from these circumstances, it is easy to be shocked that this material was endorsed by black writers to black audiences. Or, we can understand it as “love and theft.”3

When read together, these primary sources contribute to the complex tensions that lie in Eric Lott’s understanding of minstrelsy. As baffling racist as the caricatures and narratives were, the form was so popular that African-Americans had a stake in aspects of its production. Unfortunately, this seemed to be as respectable as it got when it came to minstrelsy tropes. And black and white audiences alike got on board in the names of entertainment and artistry.