Minstrel shows are characterized by stereotypes of black people imparted by white people, often with over-the-top comedy depicting caricatures of black life in America during the plantation era. So what does it mean when contemporary black performers employ these same created identities in their own work?

Comedy Central pair, Keegan-Michael Key and Jordan Peele became household names in 2012, with “East/West College Bowl” and “Substitute Teacher,” which now have a combined 228 million views on youtube.

“East/West College Bowl” is a sketch which is comprised nearly entirely of black characters introducing themselves, stating their names and from which colleges they hail. The joke is simple: each of the athletes has an increasingly “funny” and ridiculous name. This joke is not one that is original to this skit, however. The notion that black people have names that are difficult/impossible to pronounce is one that has been perpetuated for years. The humor in this skit can also be traced back to minstrelsy. A distinguishing characteristic of minstrel characters was a lack of education: mispronouncing words, the perceived inability to form complete sentences, etc.

“Substitute Teacher” challenges this idea of the uneducated black man trope found in minstrelsy, but not in the way one might assume. In this sketch, Key plays a teacher in a room full of white students. The bit here is similar to that of East/West, but different in one very important way. Instead of having the “difficult to pronounce” names being the black peoples’ names, this time it is the black teacher mispronouncing the white students’ names. In some ways, this is attempting to break the stereotype that it is black people who have difficult-to-pronounce names, but at the same time it plays into this stereotype of the uneducated black man – a common character in traditional minstrel shows.

The idea that Key and Peele could be considered a contemporary minstrel show is particularly disturbing because they are two educated black men. According to this Smithsonian article by the National Museum of African American History and Culture,

“poor and working-class whites who felt ‘squeezed politically, economically, and socially… invented minstrelsy.’”

This continued codifying of blackness furthers some of these harmful stereotypes. At the same time, their commercial success as black comics breaks them down.

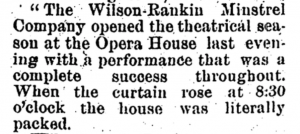

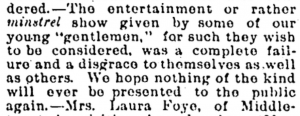

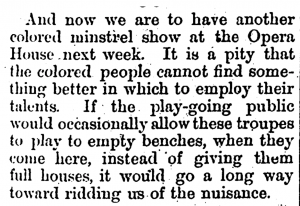

I found similar contradiction in the articles I found on the African American Newspaper database. I focused on three reviews of local minstrel shows, from the late 1880s and early 1890s. The reviews are mixed, with the Weekly Pelican describing the performance as “a complete success without,” while the Cleveland Gazette calls a similar show a “complete failure and a disgrace to themselves as well as others.” In another review, this time of a show with actual black performers and not white people in blackface, the author says, “it is a pity that the coloured people cannot find something better in which to employ their talents… it would go a long way toward ridding us of the nuisance.”

These quotes reflect some of the same sentiments of Key and Peele’s viewers today. These concerns are a part of the reason that Key and Peele no longer have a Comedy Central show, but the permanent nature of digital content and the continued views speak for themselves; audiences still connect with these deep-rooted, harmful stereotypes – and they make money.