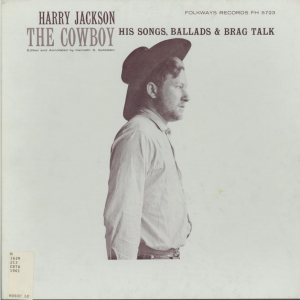

Last class period concluded with a short discussion of the ability to “buy into” the commercial market of country or hillbilly music. Based on Harry Jackson’s album “the  Cowboy” and others like it, commercial country music claimed (and still claims) geographic authenticity even though relatively little exists. This album, produced by Smithsonian Folkways, didn’t care that Harry Jackson grew up in Chicago and later adopted the cowboy lifestyle. But his music was recorded to make money, so it’s a fair guess that only so much geographic authenticity was needed.

Cowboy” and others like it, commercial country music claimed (and still claims) geographic authenticity even though relatively little exists. This album, produced by Smithsonian Folkways, didn’t care that Harry Jackson grew up in Chicago and later adopted the cowboy lifestyle. But his music was recorded to make money, so it’s a fair guess that only so much geographic authenticity was needed.

But what about the traditions that are recorded outside of the commercial market? I would think that geographic authenticity is important to someone like Alan Lomax. In 1961, the folk song collector was asked to speak at an ethnomusicology conference in Detroit. Over the course of two hours, Lomax and his wife Antoinette Marchand detailed their experiences as successful ethnomusicologists, and inserted field recordings and stories from their travels. Of the Georgia Sea Island Singers’ member Bessie Jones, Lomax says:

The reason that this material about Bessie’s sexual attitudes is so crucial, she is almost a pure informant from the middle of the 19th century back, as her repe[r]toire is composed of only the oldest classic songs, and all of her attitudes about singing are the nearest thing to the African pattern that we have found in America, the shape of the songs, shape of the music, how she treats all musical situations.1

It is important to note that the Georgia Sea Island Singers were of particular interest to ethnomusicologists like Lomax. The Georgia Sea Islands held slaves and plantations during the 19th-century just like other parts of the south. Due to the relative lack of contact with outside European cultures, the dialects, songs, and other art forms originating from in the Islands are considered by historians the purest form of West African-sourced material in America.

By 1961, Lomax had been studying the Sea Island Singers for nearly 30 years. Therefore, it was likely he knew that Jones, the most famous folk artist from the group, decided to move to the island and join the group when she was 31 years old. This begs the question, when and to what degree can we claim geographic authenticity as a marketable attribute. With regards to Bessie Jones, Lomax said:

This brings me to the real point about oral history, I think, in relationship to informants of Bessie’s level of excellence. They can give you very quickly the main emotional psychological patterns absolutely in the most complexly-stated way, and these patterns can be used for really scientific purposes, rather than sheer historical purposes, because these are the historical patterns.2

Even though Lomax’s market was much different from Jackson’s, his research (and that of other ethnomusicologists then and now) heavily relied on the authenticity of place. The degree to which audiences like us should put full faith in this authenticity is constantly in flux.

2 Lomax. Alan Lomax Collection. Image 59.

Works Consulted

Menius, Art. “Georgia Sea Island Singers, the.” In Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online, July 25, 2013. https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-1002241246?rskey=ByZc9J&result=1.

Sheehy, Daniel. “Jones, Bessie.” In Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online, January 31, 2014. https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-1002258946?rskey=nWGTbX&result=1.