Alan Lomax (1915-2002) was an American folksong scholar who dedicated his studies to searching for new folk songs to record in the rural South using an ethnographic lens. He investigated the correlation between folk song structures and melodies with folk musicians’ races, locations, and economic status. He compiled many manuscripts during his research, one of which, the “Big Ballad Book,” includes his “Appendix on Guitar and Banjo Accompaniment” [1].

He begins his appendix by describing his findings related to the differences in folk music between black and white communities. He states that white frontiersmen generally sang solo a cappella, whereas “Most Negro singing was group performed and was accompanied at least by clapping, foot-patting, and, frequently, by other instruments, played poly-rhythmically, such as the mouth-bow, the panpipe, the bones, etc.” [2], page 2.

However, according to Lomax, white folk musicians had been recently picking up influences from black musicians they met either “on the job” or “in the slums” [2], page 2. This phenomenon of stealing a culture’s music while simultaneously oppressing that culture was, and is, common among colonizers. They also encountered these ideas through the radio, recordings, and touring minstrel groups. As a result, white folk musicians began incorporating instruments into their songs.

Lomax additionally comments on the practice of judging folk music through a Western lens. As he points out, Western European harmonic traditions were formed in urban areas, whereas folk music developed in rural parts of America.

“Although Harmony is taught in schools as if its rules were laws of nature, classical Western European harmony is, in fact, just one more fashion …subject to change as the mood of mankind changes…to graft the ideas of this sophisticated urban music onto the sober, workaday back of folk music is an act of vanity and poor taste” [2], page 2.

As a result, composers like Beethoven and Copland who arranged folk songs for concert settings failed to capture the songs’ emotional tension and melodic simplicity; they made “no contribution to the lasting tradition of the song” [2], page 3. Lomax attributes this to the fact that these composers have not lived with the people from these folk traditions they are adapting from, and yet their arrangements caught on with the public while lacking authenticity.

Furthermore, Lomax highlights several misconceptions surrounding folk music. He argues that many perceive folk music as based upon improvisation rather than strict structure, and consequently feel free to adapt or arrange songs as they choose. In actuality, the minimal improvisation that can appear does so in a familiar and traditional way. He also states that while many believe that folk songs evoke individuality, a folk singer actually serves as the “mouthpiece of his culture or subculture” [2], page 5.

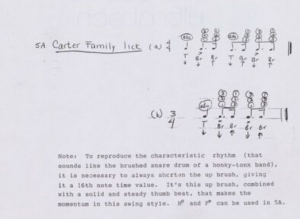

Finally, Lomax offers a beginner’s tutorial in how to play folk banjo and guitar, including diagrams of rhythmic strumming and picking patterns like “Carter Family’s Lick” and “Woody’s Lick.”

The numbers above the notes indicate which strings to pluck, 6 being the lowest string. “Abs” means ‘any bass string.’ The letters below the notes indicate which fingers to use to pluck or strum the strings; “Br” means brush the strings with the first three fingers, and “T” means to use the thumb. The arrows indicate which direction to strum.

- Lomax, Alan, and Alan Lomax. Alan Lomax Collection, Manuscripts, Big Ballad Book, -1991. to 1991, 1961. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/afc2004004.ms190316/.

- Porterfield, Nolan, and Darius L. Thieme. “Lomax family.” Grove Music Online. 2001; Accessed 23 Sep. 2019. https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000048410