Growing up in the twenty first century, my first exposure to fiddle and bluegrass music was through the white female musicians I knew. My view of women’s involvement in country, bluegrass, and “hillbilly” music, however, is different from the commonly known history of this music, which is almost entirely white and male. This difference between how I was introduced to country music and bluegrass and the earlier Appalachian styles, and how the genres, are primarily documented prompted me to search for evidence of women’s participation in country and bluegrass around the turn of the twentieth century.

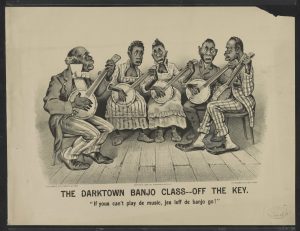

Fiddling Bill Hensley, playing the fiddle, and an unidentified woman, at the Mountain Music Festival, Asheville, North Carolina. Taken sometime between 1938 and 1950.

My searches on the database “Prints and Photographs: Lomax Collection” unsurprisingly resulted in very few images of woman in a musical setting. Lomax was concerned with documenting “hillbilly” music as he saw it: white and male. The one image that appeared to be of a woman involved with some sort of mountain music is of a white woman standing near a man playing a fiddle.1 Her stance indicates that she might be dancing. Despite the active part that many women played in making the instrumental music, this woman goes as “unidentified,” next to the named male fiddler, an example of how white women were not always written into their own history.

Jumping forward to the 1990s, we can gain a better sense of how some women viewed their participation in the early stages of bluegrass and country music from oral histories. In one interview, Barbara Greenlief recounts her grandmother’s relationship with the music of the Appalachians.2 Although her grandmother played in a local band, she hated bring that music home. In fact, “the fiddle has a real bad reputation among women in the mountains, as going along with drinking and carousing and all that.” She loved to sing gospel music and “felt a real influence of black music,” but she received little support for her musical career from her husband. While this reluctance and inability to fully embrace the mountain music she was surrounded by may be a reason that I did not find many photographs of women in music, but I suspect that it has more to do with the men who documented the music, namely white men like who wanted to create of certain image of music from the mountains.

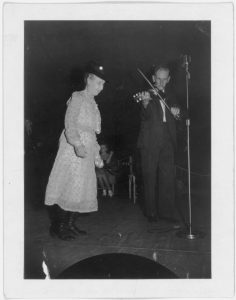

Images of black women playing music were even harder to find in these collections. While white women were marginally documented, black female country and bluegrass musicians seem to be all but absent from the early documented history. Searching the general Library of Congress database, I came across a comic from 1886 that, represents the caliber of representation in documented Appalachian music history that black women have received. The comic, part of “Darktown Comic” series depicts two black women playing the banjo alongside three black men.3 While the inclusion of these women alongside men might be encouraging in some situations, in the context of the cartoon, a crude caricature of black musicians, in this case their inclusion is only being used to further “demonstrate” black musicianship deemed unworthy of praise or attention. The cartoon depicts black characters who are not musicians because of their own instrumental abilities, but because of their “ability” to not think and let some sort of primal instinct for such music take over. It is not depiction of black female musicians, but rather a white cartoonists idea of southern mountain music.

These images and documentation, or lack thereof, confirmed my suspicions that my personal experience of bluegrass, early documentary evidence of country, bluegrass, and “hillbilly” music, and the actual participation of black and white women in this music may not all be the same. While the lack of visual documentation of white, and especially black female musicians is not unexpected, it opens the door to new avenues of research. After all, there must be a better way to demonstrate black female musicianship than by using a cartoon.

1 “Fiddling Bill Hensley, playing fiddle and unidentified woman, at the Mountain Music Festival, Asheville, North Carolina.” Lomax Collection. Library of Congress. Accessed February 25, 2018. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/lomax/item/2007660156/.

2 Yarger, Lisa. “Coon Creek Girls and John Lair’s control over their image.” Oral History Interview with Barbara Greenlief, April 27, 1996. Interview R-0020. Documenting the American South. Accessed February 25, 2018. http://docsouth.unc.edu/sohp/playback.html?base_file=R-0020&duration=02:03:20.

3 Currier & Ives. “The darktown banjo class-off the key: ‘If yous can’t play de music, jes leff de banjo go!.’ 1886. Library of Congress. Accessed February 25, 2018. https://www.loc.gov/item/91724113/.