African- American spirituals should be performed more because they represent a truth that many can relate to. You do not have to be “African-American” to understand the emotions behind silence, helplessness, struggle and liberation. But, you also do not have to be religious in order to understand the biblical references that are made in many of these songs. There is a connection in the text of spirituals that relate reality (in times of slavery) to the written evidence of the Hebrew’s slavery.

King, Willis J. “The Negro Spirituals and the Hebrew Psalms.” The Methodist Review (1885-1931) 47, no. 3 (05, 1931): 318.

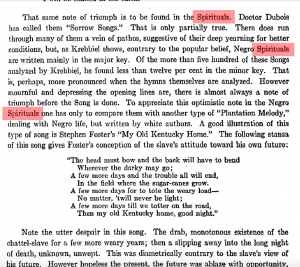

After reading the first paragraph from the article above, called “The Negro Spirituals and the Hebrew Songs” written by Willis J. King; the relationship of black slavery and biblical slavery is justifed. This whole article does a good job in comparing the similarities and differences between Negro Spirituals and Hebrew Songs. What King does best is capture the positivity that comes out of many of these spirituals. In the first paragraph in the photo above King says “However mournful and depressing the opening lines are, there is almost a note of triumph before the Song is done,” which is so true. It amazes me the amount of spirituals that are out there that are musically joyful, where the text represents very emotional and sometimes painful realities that black slaves went through. But, the beauty in these texts is that the slaves used their religious beliefs to find “triumph” and liberate themselves from the horrors that they had to live through in silence. This is just one small aspect of Spirituals, but it may be the most important because the authenticity of African-American Spiritual text is simply the truth in the message that they are putting out to mentally liberate themselves through a time of struggle.

W, you’ve found a really interesting article, and you’ve written a wonderfully thoughtful response here. Surely a joyful spirit emerges from many spirituals, partly as a result of the hopeful texts they set. But it might be interesting to complicate the narrative that “slave songs sounded happy because they were inherently optimistic.” As we read in Eileen Southern’s and Dena Epstein’s accounts, the joy in any slave song’s sounds might be inversely related to the actual feelings of the slaves singing them. The more desperate and oppressed one felt, the more need there was for bright music symbolizing not hope (or not only hope) but escape or obstinacy. Even if you disagree with this narrative (which, after all, is only another narrative and not 100% true), you probably will agree that the “slave songs are happy music” idea was long used to obscure the violence represented by those songs. Slaves sang happy songs because they were forced to, or because the oppression they experienced daily made it hard not to. We should celebrate the liberation represented by these songs, as you say, but we should also draw attention to the complicated, much darker reasons behind the sounds of spirituals that we continue to value and perform today.