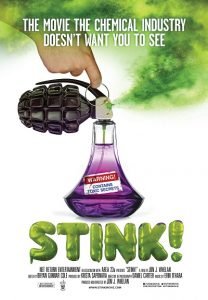

Structured in many ways like any contemporary documentary film, STINK! takes its viewers on the drawn-out journey of a single father simply wishing to do best by his children, to cope with the untimely death of his wife, and to learn what produced the odor coming from newly purchased pajamas for his tween daughter. The quest for chemical information follows a tortuous trail, moving from consumers to retailers to manufacturers with each segment enjoined with regulators, legislators, and lobbyists. Along the way Jon Whelan learns what many chemical scientists already know, manufacturers are not required to disclose to the consumer all the ingredients in a given product. At the end of the film, now knowing the identity of likely offenders in the pajamas, the audience is left to consider a lingering question. Will the disclosure and labeling requirements associated with product ingredients continue along the Business as Usual trajectory where some of the content can be hidden or will we see a disruption in this practice because of the public’s concern about their health and environmental health?

The strongest supporting storyline involves Rose and Brandon, a mother-son team battling Brandon’s severe allergic response to AXE Body Spray. AXE is a highly marketed, sexualized, deodorant product produced by Unilever. Rose makes inquiries to Unilever about the possible chemical to which her son reacts only to be given no assistance in the matter. The family physician wants to do a myriad of chemical tests to determine the culprit, and Brandon simply wants to know what to avoid so he can return to school. Even with the community support, minutes after entering the school Brandon is hit with an AXE scent, forced to use his EPI-PEN, and sent to the hospital. This scenario plays out frequently for parents of children with severe allergies and chemical sensitivities every day in schools, churches, and on family vacations.

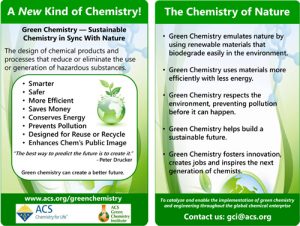

While the film does a reasonable job illustrating how manufacturers use trade secret protections and the fragrance exception to limit full disclosure on ingredient labels, it missed a number of opportunities. Excellent examples from chemical classes of concern make appearances in the film; however, the simple truth that we and all living organisms live in a natural and toxic chemical soup gets no play. Human beings are not the only organism that creates highly toxic chemicals or to be exposed to naturally occurring toxicants. Just think about arsenic, lead, and mercury or the host of botanicals – foods and herbs – not fit for human use and consumption. In addition the film fails to lift up the positive practices across the chemical enterprise – companies promoting full disclosure and doing things different. No mention of the practice of green chemistry enters any frame, and this year, 2016, marks the 20th anniversary of its introduction. These points represent critical omissions. While it is inconvenient to layer this nuanced approach to the chemical enterprise, it is honest and essential.

While the film does a reasonable job illustrating how manufacturers use trade secret protections and the fragrance exception to limit full disclosure on ingredient labels, it missed a number of opportunities. Excellent examples from chemical classes of concern make appearances in the film; however, the simple truth that we and all living organisms live in a natural and toxic chemical soup gets no play. Human beings are not the only organism that creates highly toxic chemicals or to be exposed to naturally occurring toxicants. Just think about arsenic, lead, and mercury or the host of botanicals – foods and herbs – not fit for human use and consumption. In addition the film fails to lift up the positive practices across the chemical enterprise – companies promoting full disclosure and doing things different. No mention of the practice of green chemistry enters any frame, and this year, 2016, marks the 20th anniversary of its introduction. These points represent critical omissions. While it is inconvenient to layer this nuanced approach to the chemical enterprise, it is honest and essential.

As noted journalist and author, Deborah Blum states, “Everything is built by chemistry. I am. My chair, my table…an intricate mosaic of interactions; this incredible dance of chemical elements creates everything around us.” This film reminds us that for years creative human beings employed chemical principles to fashion new materials that extend the ability of our species to thrive. Over the last 60 years we slowly re-awakened to the limits of that creativity, namely the less than positive consequences of material design, intentional and unintentional, on human and environmental health. Citizen consumers can make change and even disrupt business as usual by purchasing materials from companies willing to disclose all their ingredients, by supporting manufactures following the principles of green chemistry, by getting educated, by engaging in the political process, and by befriending a scientist, like me.

Lights, camera, action! Enjoy the show.