In addition to writing online blog posts, we students write personal journals about our experiences abroad. We continually find ourselves sharing in unfamiliar cultural practices, and reflection journals help us step back from these experiences and interpret the Japan world with a positive, receptive outlook.

Morning woodchopping

Journaling is an especially helpful way to interpret new experiences in this study abroad course, in particular. We are not only encountering challenging cultural experiences by living in Japan—we are also encountering a radically different lifestyle by eating, sleeping, and laboring as part of a rural farming community. Imagine waking up at 6:30am to share a morning’s manual labor and a leisurely breakfast with a community of farmers—not quite the same as stopping by the Starbucks drive-thru on the way to a morning at the office. Every day we find ourselves helping with jobs we hadn’t known to exist, and every day we find ourselves engaging in conversation with people who hold entirely different worldviews. Journaling helps us reflect on our experiences and grow from our time in Japan.

We received the first journal prompt before settling into the Asian Rural Institute’s (ARI’s) farming community: “What is ‘good’ food?” At this time, our class had just spent two days in Tokyo slurping on ramen, wandering markets, and otherwise enjoying metropolitan Japanese food culture. One of my favorite finds during our Tokyo explorations is the glorious strawberries-and-cream stuffed waffle taco—analogous to something like an enlarged strawberry flavored Twinky prepared with too much filling. If there was such thing as ‘good’ food, it had to be the waffle taco.

The glorious strawberries-and-cream stuffed waffle taco

Excluding the waffle taco and its self-evident superiority as a food source, this first journal prompt was actually rather difficult to answer. What is ‘good’ food? Is there even such thing as ‘good’ food? How does someone determine what makes food ‘good?’ Taste? Nutrition? Cost? I found this question to be a worthwhile one to ask. When we choose the foods we eat, what elements contribute to our choices?

In my response to this journal question, I took a developmental approach: I described how I understood my own perspective on ‘good’ food to have developed across three stages throughout my life.

In the first stage of development, I believed ‘good’ food was good-tasting and convenient. Doritos, for example, was my go-to snack in middle school. All I had to do was grab a bag from the pantry, and I would have a feast of salty, ranchy goodness in my belly, on my fingertips, and probably in my arteries as well. And this was perfectly okay with me: when I was 13, the integrity of my arteries was a sacrifice I was willing to make for another handful of chips. In this way, I understand the first stage of development to be concerned with the short-term, self-interested goods of taste and convenience.

In the second stage of development, I incorporated health and affordability into my understanding of ‘good’ food. I began to take responsibility for my own money, and I realized that I might actually care about my arteries. It was in early high school that my values began to shift. Instead of instinctively reaching for a bag of Doritos, I would take a moment to first open the fridge and see what kind of healthful concoction I could put together. An apple, a bowl of pistachios, some leftover chicken from last night’s dinner. I would still go for the Doritos from time to time, but feeling healthy became something that mattered to me, too. In this way, I understand the second stage of development to be concerned with the long-term, self-interested goods of health and affordability.

Sleeping chickens on ARI’s farm

In the third stage of development, I began to consider the larger ways in which the food I eat is connected with the world. Animal welfare, for example, became an ethical concept that informed my food choices. I distinctly remember browsing YouTube as a freshman in high school and stumbling upon a video that exposed footage of chickens, pigs, and cows suffering in factory farms. I won’t describe any details of this video, but to me it felt something like the infamous dog shelter commercial, in which images of abused dogs are displayed to the lyrics of Sarah McLachlan’s “Angel” (listen here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nadx6OFsuHg). For quite some time, I couldn’t eat meat without seeing images of suffering animals and feeling the music underlying this powerful commercial. The mental gap between ‘chicken,’ the living bird, and ‘chicken,’ the piece of meat, merged together in my mind, and I became passionate about the ethics of animal welfare. In this way, I understand the third stage of development to be concerned with worldly goods such as animal welfare, human rights, and environmental sustainability.

When I originally journaled about these three stages to my perspective on ‘good’ food, our class had only just arrived in Tokyo. Looking back on my journal response today—after our class has had the opportunity to reflect on the relationships among food, people, and nature in ARI’s farming community—I now understand my three stages of development to be incomplete. I now see a fourth developmental stage, which I was previously unable to comprehend.

Masanobu Fukoaka’s “The One-Straw Revolution”

This missing fourth stage became clear to me as I read Masanobu Fukoaka’s book, The One-Straw Revolution. Fukoaka is a Japanese farmer who developed a “do-nothing” approach to farming. As both a scientist and farmer with an appreciation for Zen Buddhist philosophy, Fukoaka has a colorful history of experiences and viewpoints. In a chapter on diet, Fukoaka does precisely what I set out to do in my journal response: he provides a framework for understanding the development of our diets. If Fukoaka were to approach the question of “What is ‘good’ food?”, his response might resemble the following excerpt from The One-Straw Revolution.

“In this world there exist four main classifications of diet:

(1) A lax diet conforming to habitual desires and taste preferences. People following this diet sway back and forth erratically in response to whims and fancies. This diet could be called self-indulgent, empty eating.

(2) The standard nutritional diet of most people, proceeding from biological conclusions. Nutritious foods are eaten for the purpose of maintaining the life of the body. It could be called materialist, scientific eating.

(3) The diet based on spiritual principles and idealistic philosophy. Limiting foods, aiming toward compression, most ‘natural’ diets fall into this category. This could be called the diet of principle.

(4) The natural diet, following the will of heaven. Discarding all human knowledge, this diet could be called the diet of non-discrimination.

People first draw away from the empty diet which is the source of countless diseases. Next, becoming disenchanted with the scientific diet, which merely attempts to maintain biological life, many proceed to a diet of principle. Finally, transcending this, one arrives at the non-discriminating diet of the natural person.”

When I first read this excerpt, I was ecstatic. The three developmental stages from my journal response mapped remarkably well onto Fukoaka’s first three classifications of diet. Fukoaka’s “lax diet” resembles the “short-term, self-interested goods” in my first stage of development; Fukoaka’s “standard nutritional diet” resembles the “long-term, self-interested goods” in my second stage of development; and Fukoaka’s “diet based on spiritual principles and idealistic philosophy” resembles the “worldly goods” in my third stage of development. I gave myself a mental pat on the back for having sketched such a similar classification system. I look to Fukoaka’s lifestyle and perspectives with great admiration, and I was proud to have independently arrived at a similar understanding of the development of our diets.

I was, however, still missing an explanation for Fukoaka’s fourth stage of classification. What is the “natural diet?” Fukoaka’s developmental progression includes this fourth stage—transcending the three I had described in my journal response—and I was curious to learn about its perspective. I set out to piece together the meaning of the “natural diet,” and I started by rereading Fukoaka’s words:

“The Diet of Non-Discrimination

Human life is not sustained by its own power. Nature gives birth to human beings and keeps them alive. This is the relation in which people stand to nature. Food is a gift of heaven. People do not create foods from nature; heaven bestows them.

Food is food and food is not food. It is a part of man and is apart from man.

When food, the body, the heart, and the mind become perfectly united within nature, a natural diet becomes possible. The body as it is, following its own instinct, eating if something tastes good, abstaining if it does not, is free.

It is impossible to prescribe rules and proportions for a natural diet. This diet defines itself according to the local environment, and the various needs and the bodily constitution of each person.”

Fukoaka’s characterization of a “natural diet” took some time for me to grasp. How can ‘food’ be both (a) ‘food’ and (b) ‘not food?’ Isn’t that a paradox or something? I might have considered throwing my book after reading that apparent contradiction, but I actually bought the Kindle edition for my laptop. I therefore decided to not throw my laptop and think about Fukoaka’s words instead.

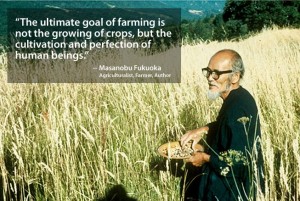

Masanobu Fukoaka

To my limited understanding of Zen Buddhism, a core element of spiritual practice is to let go of assumptions about reality that are not enlightened. For example, consider believing that you are entirely disconnected from your food. Imagine that you—as a civilized human being—do not have any connection whatsoever to the biological processes and human efforts that work together to produce strawberries, fish, deep-fried Oreos, or whatever it is you eat. Strawberries mature and are harvested in World Unreality, and you eat strawberries in World Reality. Pretend that you believe this, and see what it feels like.

This is where paradox plays a role in Zen Buddhism. According to Zen theory, rational thought (i.e. ‘discriminating’ thought) makes sense of the world through rational concepts, and these rational concepts tend to carry assumptions about reality that are unenlightened. The belief that you are entirely disconnected from your food is an example of an assumption about reality that is unenlightened. This belief does not help you live mindfully and truthfully. It separates you from your natural connection with the environment and other beings, and this clouds your mind.

Paradox, then, can be used to disturb the rational concepts that you have about food. Consider, again, Fukoaka’s suggestion that “food is food and food is not food.” The intention of these words is to help a person let go of rational concepts associated with the word ‘food.’ Take a moment to reread Fukoaka’s words, and really feel the tension in your thinking: “food is food and food is not food.” By challenging the entire framework of thought attached to the word ‘food,’ this paradox opens the imagination. It frees the mind from the misinformed belief that you are disconnected from your food, and liberates one to discover truth and joy in the natural world. This is how paradox can be used to help a person work beyond the first three classifications of diet, and realize Fukoaka’s fourth stage of development: a “natural diet” of non-discrimination. Notably, the role of enlightened thinking in this diet demonstrates how a “natural diet” is more than just a diet, an enlightened way of eating—it is a lifestyle, an enlightened way of living.

We eat lots of rice!

In my experience, I have noticed one particular discriminating concept that attaches me to the second classification of diet (i.e. the “standard nutritional diet”). Specifically, this discriminating concept is the belief that I need to eat a particular quantity of protein to be healthy. A lot of contemporary nutritional doctrine advocates the consumption of high quantities of protein, and I have been programmed to hold this perspective on a pedestal. When our community at ARI eats together in the dining room, we eat limited amounts of protein. We tend to eat a lot of rice and vegetables, and when we eat meat or eggs, we share it in moderated portions. Accordingly, I notice that I sometimes feel unsatisfied when there is not much protein to go around the table. My narrow belief that ‘good’ food is high-protein food pressures me to adopt a diet centered around protein consumption, and as a result I feel tension when nature has other plans for my meals.

Before sharing meals as a part of ARI’s community, I have had the luxury of choosing from an exceptionally wide variety of foods. In the St. Olaf cafeteria, we are lucky to select from a huge assortment of delicious options, and in my family’s home, we regularly enjoy home-cooked meals and a fully-stocked refrigerator. In both of these settings, I have access to limitless quantities of protein, and my second-stage diet goes unchallenged. It is routine for me to eat to nutritional doctrine—rather than what Fukoaka calls “the will of heaven”—and this habit obstructs my realization of a “natural diet.”

The adjustment to ARI’s setting of natural farming and community eating is a valuable experience for me. The truth is that many people in the world do not eat much protein at all. Nature does not have the capacity to provide seven billion people with a diet tailored for polished athletes, and I cannot expect to have access to abundant quantities of high-protein animal products at each meal. In ARI’s community, I have the opportunity to practice eating in harmony with nature. We collect eggs from our chickens, harvest carrots from our fields, cook meals in our kitchen, and share food as a community. I am part of this community, and at mealtimes I am challenged to let go of my attachment to protein. Internet articles about nutrition and the viewpoints of my weightlifting friends have programmed me to assume the mindset that ‘good’ food is high-protein food. When I choose to grab a second helping of vegetable soup and pass the last hardboiled egg to another community member, I am learning to set aside that mindset and realize that a second helping of vegetable soup is ‘good’ food. Nature gives us all that we need and more.

In this way, ‘good’ food is not high-protein food. ‘Good’ food is not the expectation in my head that I consume protein, enjoy a deep-fried Oreo, or avoid meat produced in factory farms. ‘Good’ food is the beautiful meal prepared by my classmates and enjoyed in community. The “natural diet” transcends allegiance to protein consumption, gourmet dessert, vegetarianism, and any other rational scheme of eating: there is no single category of ‘good’ food in a “natural diet.” Nature provides a satisfying, healthful, righteous balance of simple foods for us to enjoy in harmony with our pursuits and relationships. All food is ‘good’ food when it is appreciated in a wholesome union with nature, and I believe that this is what Fukoaka meant in his characterization of a “natural diet.”

ARI sunrise

I am so thankful to experience natural eating in ARI’s community. From farm to fork our food is naturally produced, and I enjoy the transparency and simplicity of every meal. When I return to the United States, I want to continue to practice a “natural diet.” I want to make wholesome food choices and appreciate the origin and beauty of my food. In the United States, however, most food is not natural food. How can I appreciate the origin of a burger that is mechanically shaped from the meat of hundreds of hormone-injected animals? How can I appreciate the origin of strawberries coated in pesticides and picked by exploited laborers, hundreds of miles from my plate? At ARI, we produce our own food with natural methods and we stand behind every ingredient. But in the United States, the large majority of our food is produced within the system of agribusiness. How can I make wholesome food choices when I return to the United States? How can I practice a “natural diet” within an unnatural system? This is a question for another blog post (https://pages.stolaf.edu/esj-2016/2016/01/11/the-stories-behind-our-food/).

Recent Comments