A Beginner’s Guide to News Writing

The Messenger’s news section fills pages A1 and A7 of the weekly paper. Because the Messenger serves at the paper of record for the St. Olaf community, it’s important that our articles are well written, accurate, and backed by solid reporting. If you’ve just claimed your first news story or you’re looking to brush up on your reporting and news writing skills, take a look at the information below.

Finding a story

The Messenger’s news editors will pitch potential news stories every Sunday, but it’s helpful to them if you’re keeping an eye and ear out for news, too. A good journalist is always looking for a story, whether they’re on the clock or not. Are your friends complaining about worms in the cafeteria spinach? That could be a story. Did Bon App change their offerings from Coke to Pepsi products? That’s definitely a story. Did your friend on the baseball team break his arm? A story. Learn to strengthen your story-spotting muscle by…

Use common sense. Your friends won’t like you much if you start writing about conversations that they assumed were private. Though looking for news is a 24/7 job, remember that you’re also a student and a human being. If you hear a news tip while you’re off the job, ask if you can schedule an interview with that person to discuss it on the record.

- Paying attention. Learn to look for news everywhere. Pay attention to what’s going on around you, what your friends are talking about, and what you see on campus. The Messenger has found interesting news leads in faculty meetings, Facebook groups, class discussions, conversations with friends, and even menu changes in the cafeteria. Trust your gut – if you think that something could be newsworthy, it probably is.

- Staying on top of events. The campus events calendar is packed full, so check it regularly to find out what’s going on. Instead of writing only about the event, see if you can dig deeper. How did the planning go? Who is paying for it? What is the target audience? Was campus happy or unhappy with what happened?

- Watching your social media. Facebook pages, groups, and events can be great ways to find news leads. For more information about utilizing social media for news reporting, check out our info page.

- Getting out of the office. The best stories won’t magically appear in your inbox. If you’re at a loss for ideas, go talk to people!

If you want to be a reporter post-college or a section editor later in your Mess career, developing story ideas will be critical. Strengthening that muscle now will give you a leg up during application season.

Talking to sources

Once you’ve got a story idea, determining who to talk to and how to talk to them is critical. That’s why we’ve dedicated an entire page to sourcing and interviewing – it’s here.

Choosing quotes

Good quotes breathe life into news writing and are critical to good story telling. Keep the following in mind when choosing which quotes to include in your piece.

- Relevance. Only include quotes that enrich your reporting. Don’t pepper your article with unnecessary and confusing comments. Did your source say it better than you can write it? Great, include that quote. If not, paraphrase the information.

- Balance. Do your best to include perspectives from all relevant parties. This will ensure that you’re reporting on the entire story, not just part of it. That being said, don’t include irrelevant dissenting voices for the sake of balance itself. This is often an issue when soliciting student opinion on campus events. For more info, see the info box below on soliciting student opinions.

- Proportion. Quoting one student six times in an article gives that student a powerful platform to voice their thoughts. While quotes can be a very useful way to showcase community response to an issue, be sure to include a mix of voices so that no one person dominates the conversation.

- Friends and family. Unless they are directly relevant to your story, don’t seek out friends and family for comment. It’s lazy.

- Language. The Messenger doesn’t publish profanity. Many times, words can be censored, but steer away from quotes that require a lot of scrubbing. See the stylebook for a list of words that we cannot print.

- Attribution. The quote you’re using is on-the-record, right? Don’t quote anonymously unless you have consulted your editor.

Don’t be a quote doctor. One of the benefits to recording your interviews is that you can ensure your quotes are completely accurate. Be sure to listen to them a second, third, or fourth time if you’re unsure about wording. On the occasion that you need to replace a word for clarity, put the substituted word in brackets: [ new word], but do so sparingly. Made-up or doctored quotes are unethical and can result in libel or defemation charges, so make sure you heard it right!

When you’re soliciting quotes from bystander students to gauge campus opinion in an article, as we often do in stories about campus events and policy changes, ask yourself: Are you best friends with this student? Have they been quoted in recent articles? Do they seem clueless as to what’s going on? Did they at any time refer to themselves as a “devil’s advocate”? If the answer to any of those questions is “yes,” find someone else to quote.

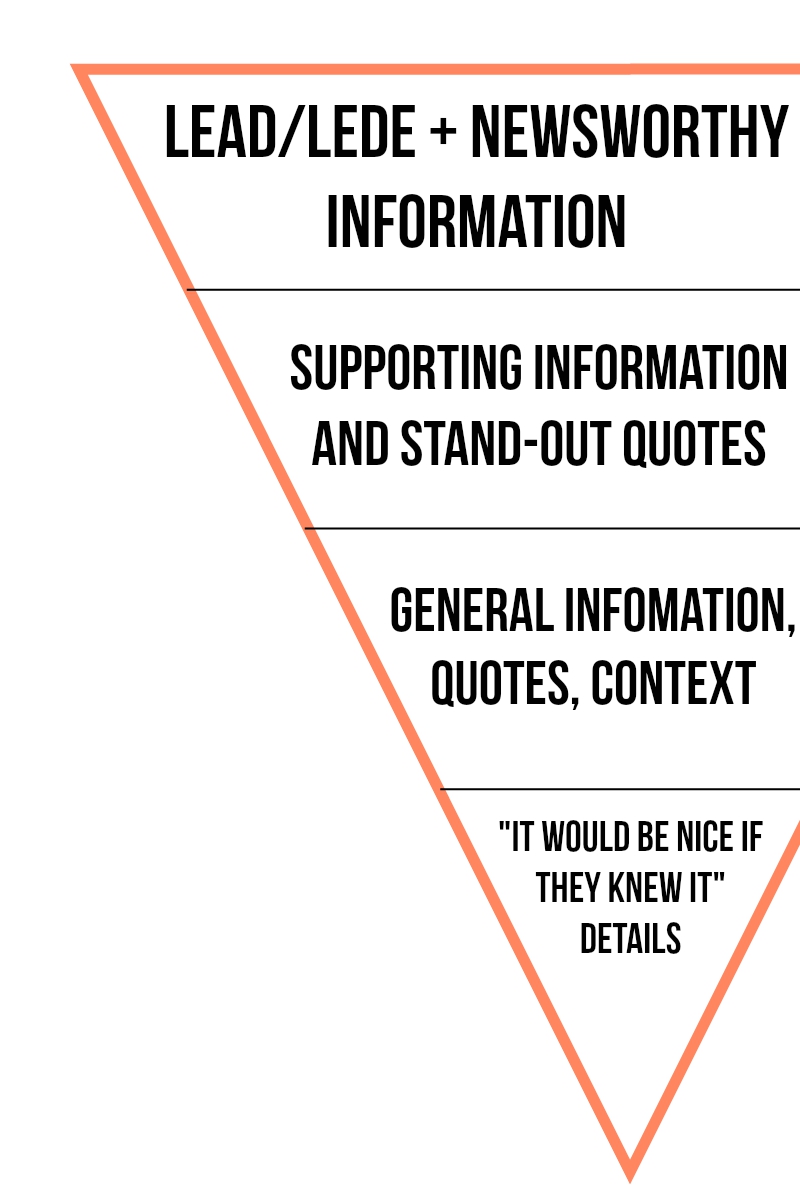

News writing style: the inverted pyramid

Unlike academic or creative writing, hard news writing includes little fluff and is generally short. The “inverted pyramid” is a good way to think about outlining your news story. Keep in mind that soft news, like features or profiles, as well as long-form journalism like investigative pieces, stray from this format and follow a more story-like structure.

The inverted pyramid style was created so that editors could easily trim articles to fit the space available on the page, but it continues to be useful in the digital age. The average reader will spend about 30 seconds looking at your story, so putting the most important information at the top ensures that they can understand the purpose of the story in those 30 seconds. For the most part, news stories should follow a similar outline to the one below:

- The lead – (or lede, as it’s sometimes spelled) is your hook. Get the reader interested. DO NOT start with “On Monday, June 3 …”

- The first paragraph – or “graphs,” as you’ll often hear them called – of your news story should answer the question – why is this newsworthy? In a nutshell, what’s the point of your story? This section is often referred to by editors as a nutgraph. News stories to not include introductions, just get right to the point. Answer the questions who? What? Where? When? and Why? for the reader.

- The following few grafs should include supporting details and further information. Expand on the 5Ws – who, what, where, when and why – for the reader. Make sure to introduce all of your sources in this middle section.

- Some news stories will benefit from providing historical background or context. If readers would benefit from some contextualization of the news you’re reporting, include it in the bottom half of the story.

- Nearing the end of your news story, include details and extra quotes that the reader might appreciate, but aren’t necessary for understanding the information.

Fact Checking

Fact checking is the most important part of the news writing process. Getting anything wrong – even small details like the spelling of a name or the start time of an event – can call into a question the credibility of the entire story. Mistakes happen, but most corrections that the Messenger issues are entirely preventable with good fact checking. Below is standard procedure for fact checking an article before it goes to print.

Review quotes – Did you hear everything correctly in your recording? Do the quotes make sense? Be sure that you’ve situated the quote well in your story, so that readers understand why you’ve chosen to put the quote where you did; bad contextualization can lead to misinformation. If you’re unsure about what someone said, don’t guess. Give them a call or send them an email to review the quote and ensure its accuracy.

Double check details – Give your piece some thorough copy editing. Are all of the source names spelled correctly? Are class years right? What about event times, dates and titles? DO NOT rely on the copy editors to catch these kinds of mistakes. Your story should be solid before its submitted to any editor.

For more serious pieces, the fact checking process is much more intense. For example, when the Messenger published several stories about sexual misconduct by professors, the editors and writers involved met as a group and vetted the piece line by line. Some sources – at the discretion of the editor – were able to review their quotes for accuracy. In both cases professional journalists and a media lawyer also looked over the piece. If you think your story carries some weight, be in communication with your editors every step of the way, and be sure to include them in fact checking process.

A word about advanced copy: NO ONE besides the Manitou Messenger editors has the right to read your story before it goes to print, even if they tell you otherwise – not the faculty advisor, college administrators, outside counsel, your trusted source, etc. If someone is asking for advanced copy, the answer is always no. There are some cases (like the example above) where editors will seek professional eyes to look over a piece, but only after careful consideration of the interests of all parties involved.

There are times when sources may ask to see their quotes – consult your editor before granting that privilege. In extremely delicate cases, it is recommended that you call your source in advance of publication and walk through the quotes and information that they have provided to ensure accuracy. Be careful that you do not just recite the story aloud.