Information, Materiality, and the Posthuman

SPOILER ALERT: This analysis will go into significant story details for Tacoma and The Talos Principle.

At the center of posthumanism, one idea reigns supreme: the idea of the posthuman itself. While ideas like artificial intelligence, the human apocalypse, and flat ontologies are important to the larger conceptions of posthumanism, the posthuman is the core idea at the center of this ideology.

But what exactly is a posthuman? There are as many definitions of posthuman as there are concentrations within posthumanism, so it can be hard to settle on one definition. Therefore, instead of defining the posthuman, describing it is more effective, and Katherine Hayles’ description in How We Became Posthuman digs into the core of the posthuman. Though she listed a number of characteristics, her most striking idea is that life is not something related to consciousness. Instead, the capability to interact with information in the environment, what I’ll call an “information system,” is what defines life (1).

An “information system” might seem scary and complex, but in practice, they can be quite simple. For example, when a human body detects that it’s hot, it sweats to cool the body. The human body receives information about the environment (it’s hot), and acts on it (it sweats). Information systems can obviously be more complex, but at their core, information systems are an object noticing something in its environment and then modifying itself to accommodate that thing.

However, for an object to respond to an information system, it needs a physical form. When information exists, it exists in a physical form, regardless if that form is a page of a book, a person’s brain, or a line of code (2). This is doubly true for information systems, as for something to be able to respond to information provided to it, it needs some sort of materiality, some form, in order to be able to react to the information provided to it. These forms are often called “objects.”

At the most basic level, a posthuman is an object that can engage with an information system.

That absolutely cannot be all that constitutes a posthuman, since “an object that engages with an information system” could describe literally anything. Sunflowers receive information on the sun’s position and turn their body to face it. Just because that sunflower acted on information doesn’t make it a posthuman. There’s something more to the posthuman than an object engaging with an information system. That statement is something that two video games, Tacoma and The Talos Principle, would agree with. Examining the way these two video games treat instances of artificial intelligence makes it near impossible to believe that all a posthuman needs is a vessel capable of reacting to an information system.

Tacoma, a 2017 narrative experience, clearly shows that there’s more to the posthuman than a material body and the ability to interact with information. Tacoma takes place on an abandoned space station in 2088 after humanity made a functioning artificial intelligence. Players can see the past actions of the Tacoma crew (who are no longer on the station) thanks to augmented reality technology on the station. Players can also see the artificial intelligence on the station, ODIN.

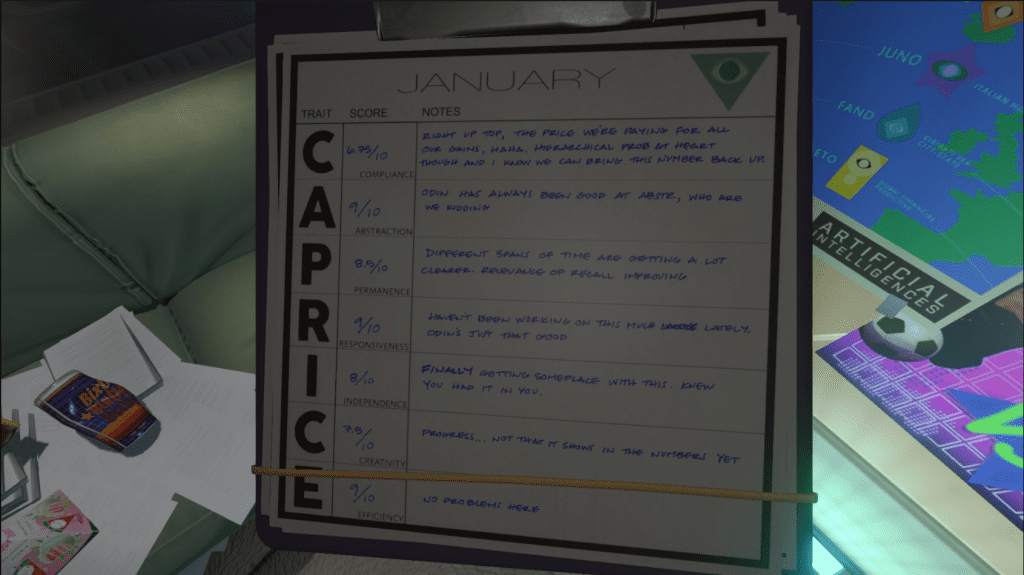

If players find the network and artificial intelligence specialist’s (Natali) workspace, they can read about CAPRICE, a scoring system used to evaluate different personality traits of ODIN. (See Figure 1)

Figure 1: Network specialist Natali Kuroshenko evaluating the station’s artificial intelligence, ODIN, on seven different personality traits. For those that cannot read the screenshot, these traits are: compliance, abstraction, permanence, responsiveness, independence, creativity, and efficiency.

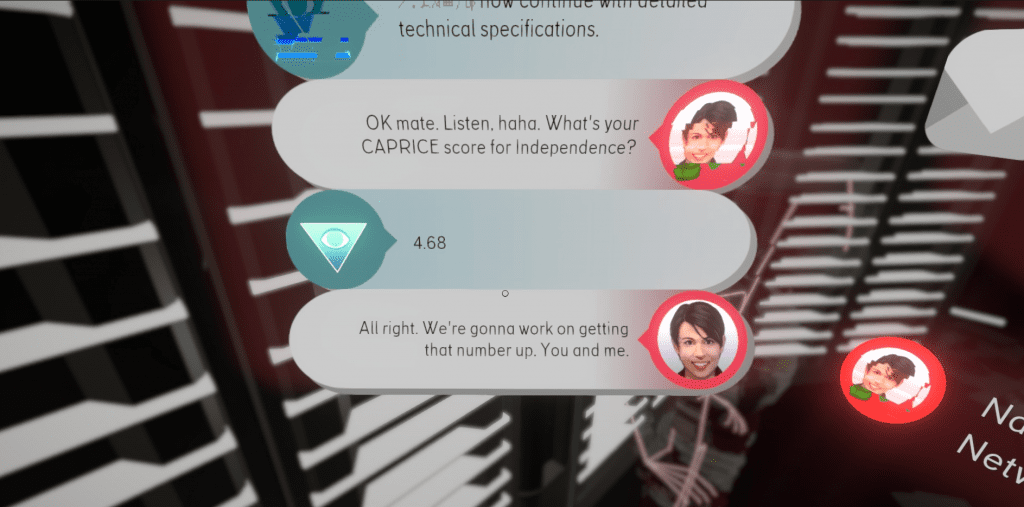

Every month, ODIN undergoes an evaluation to determine if his CAPRICE has changed. ODIN is certainly functional as he interacts with the crew, but there’s a consistent desire for ODIN to improve and change himself, which can be seen in some personal communications, like the one in figure 3.

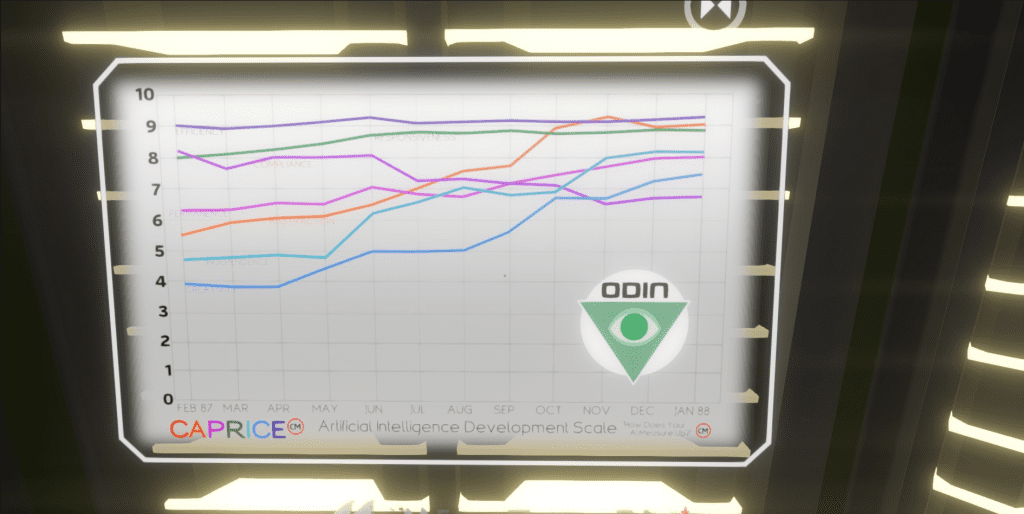

Figure 2: ODIN’s CAPRICE scores over the span of a year. Pink is Compliance, orange is Abstraction, light purple is Permanence, green is Responsiveness, greenish blue starting at ~4.7 is Independence, light blue is Creativity, dark blue is Efficiency.

Figure 3: Natali wants to improve ODIN’s independence.

Even though ODIN can process information and has a material form, that isn’t enough for Natali. ODIN needs a sense of self that is separate from other entities. Natali isn’t the only one that believes that it’s important for ODIN to be independent. As the game ends, the playable character, as a representative of an artificial intelligence activist group, offers ODIN political asylum, as they believe that ODIN’s “safety and autonomy are in grave danger if [he remains] in the possession of the Venturis Corporation,” and then lets him decide his fate.

Between CAPRICE scores and the reasoning of the activist group, Tacoma clearly says that embodiment and information processing aren’t the only two things that a posthuman deserves. According to Tacoma, the posthuman needs independence.

Though for different reasons than Tacoma, The Talos Principle also believes there’s more to the posthuman existence than information and materiality. In The Talos Principle, players control an android in a computer simulation. Before humanity went extinct, they coded a program in an attempt to create an intelligence to inhabit Earth after humanity. This simulation is run by Elohim, a mysterious being that exists to test the android created by the program for two things: intelligence and free will.

“I have created trials for you to overcome and within each I have hidden a sigil.” Players complete puzzles, justified as tests of intelligence in the game, to progress in the story.

When an android displays intelligence and free will, then they have “completed the test” and are uploaded into a mechanical body in the real world. They are set loose upon Earth and are meant to be a race to succeed humanity. However, if they fail the tests, then their memory banks are reset and they begin the entire testing sequence all over again.

To the original creators of the simulation the game takes place in, materiality is a privilege that only a certain type of information pattern can inhabit. Less efficient or valuable information could gain a material form, that happens all the time. But the designers of the simulation in The Talos Principle believe that there needs to be more than just information in a material body, it must be able to decide what to do with information on its own and make high quality decisions.

Tacoma and The Talos Principle are clear with their message: the posthuman needs to be more than an object engaging with an information system. The posthuman might need intelligence, it might need free will, or it might need to acquire specific personality traits. As humanity approaches a future where these types of posthumans might become more and more prevalent, keeping this need for more in mind is critical to creating healthy, properly functioning posthumans.

1 – Hayles 3.

2 – Hayles 13

Dr. Rebecca Richards (St. Olaf College, Northfield, Minnesota) curates Thoughtful Play.

If you’re interested in creating your own project for Thoughtful Play, contact thoughtfulplay64@gmail.com

0 Comments