How Do Games Make Nonviolent Conflict Engaging?

In the introductory page to this project, I claim video games have a problem with violence because they over rely on it to construct conflict. In all entertainment media, conflict is the overarching term that refers to the core struggle of a character in a story. In a sports themed story, the conflict might be a group of athletes trying to win a competition; in a superhero story, the conflict will probably be a superhero trying to stop a supervillain. Characters work towards their goals with a variety of means, but in video games, conflict occurs almost exclusively through violent means. In moment-to-moment play, games rely on violent, life-or-death conflict to create engaging gameplay moments. With game narratives, characters consistently set inherently violent goals.

If conflict keeps players engaged and games overwhelmingly rely on violence to create engaging conflict, how can nonviolent games engage players? If games don’t let players work against other agents, how can games engage players? Two games, The Witness and Animal Crossing: New Horizons, demonstrate how nonviolent games can craft unique, engaging, nonviolent conflicts.

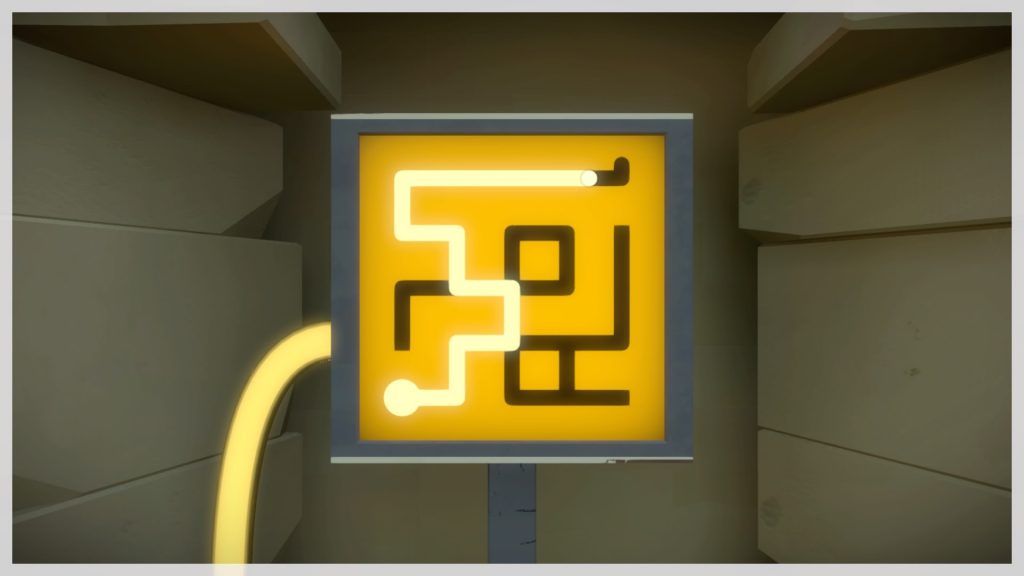

The Witness, developed primarily by Jonathan Blow, sticks players on a mysterious island filled with hundreds of puzzles. They aren’t given any direction, the game simply presents the island and hundreds of puzzles silently challenging players to uncover as many solutions as they can. Puzzles appear in panels like these:

Players solve puzzle panels by drawing lines on them. Players start at specific points on the panel and need to draw a line to the endpoint of the puzzle while obeying all of the rules of each puzzle.

The puzzles in The Witness start out simple. At first, players just need to draw lines between the starting and ending point, like this:

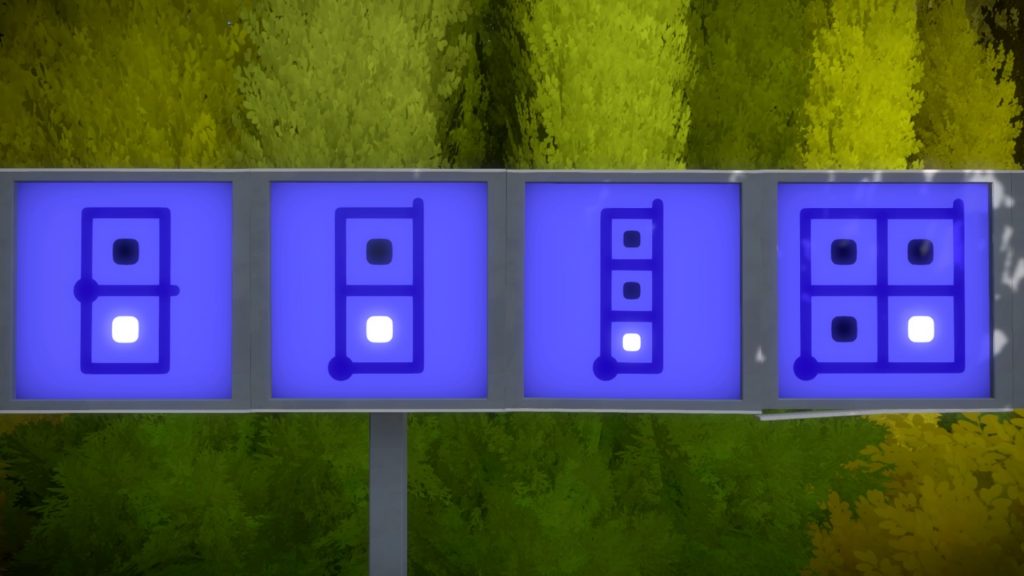

The game quickly introduces more rules for players to follow in their line drawing. After finishing the first area, players will come across panels with black and white squares:

The game doesn’t explicitly tell players what these squares mean. Instead, over the course of a few puzzles, the game slowly shows how the puzzles work by guiding players through easy puzzles. If players try to solve the first puzzle by going over the black box, like this:

The game rejects their solution:

Only by drawing the line straight through, separating the white and black boxes, does the game let the player progress on to the next puzzle. The game gradually increases the complexity of the puzzles while never confirming the specifics of how a square type works.

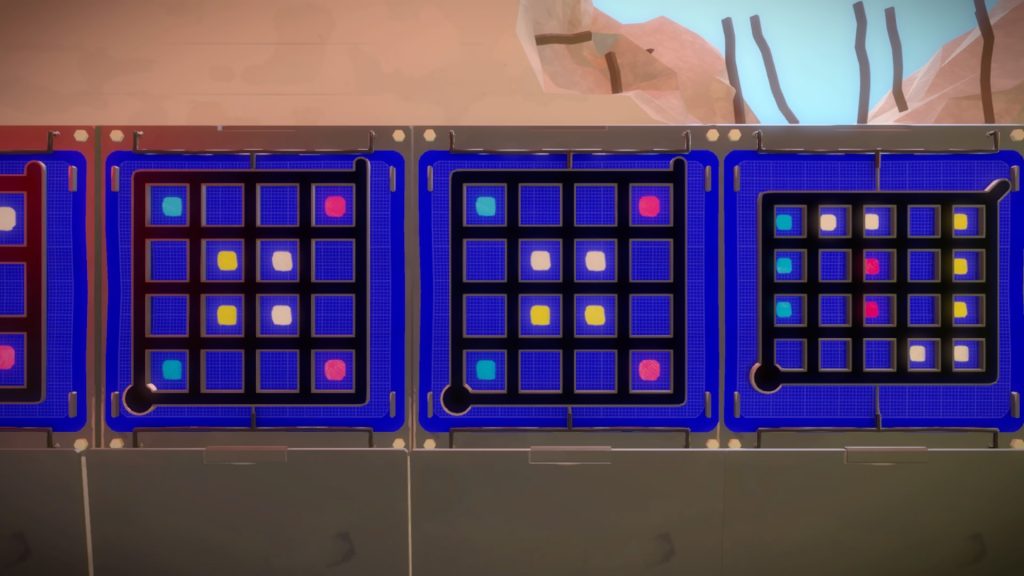

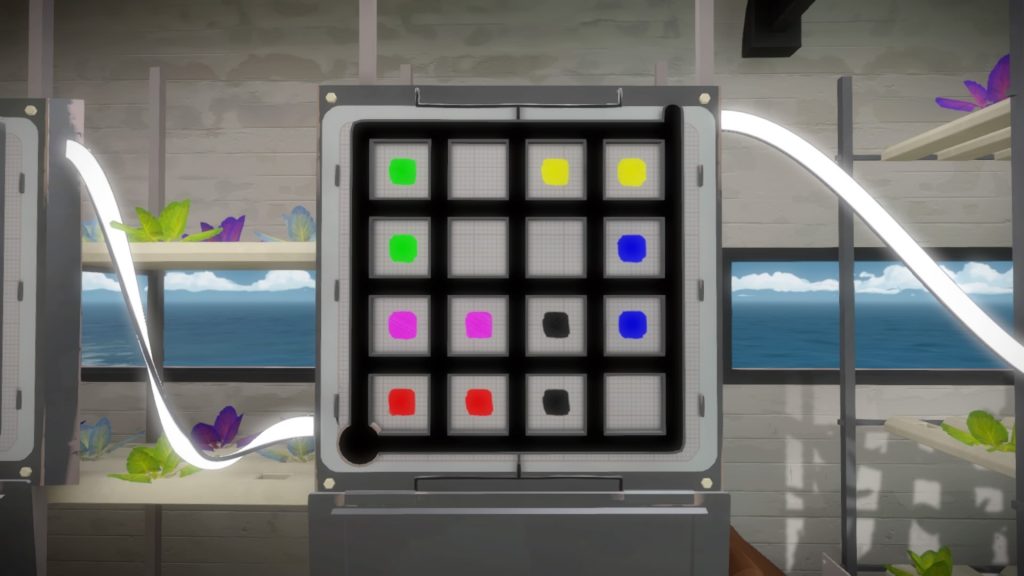

The key to The Witness creating engaging goals lies in its nonverbal teaching of puzzle rules. The Witness frequently adds twists to the rules it introduces, and most of the game’s challenge comes from trying to understand the different twists the game adds. In one area of the game, a building filled with multicolored rooms and colored glass, the game introduces a puzzle type where players need to split the different colored squares into different sections:

After players solve a dozen puzzles like this, they come across a panel that looks like this:

No matter how players draw lines, they can’t split all of the colors there into different sections. The only way to solve the puzzle is to think outside the box and view the panel through a pane of colored glass nearby:

Many puzzle types in The Witness require players to think about nearby environmental elements like this. The game constantly makes players reconsider elements of the game they originally thought were trivial. With these puzzles, The Witness creates a goal for players to work towards: correcting their flawed mentality.

Nonviolent gameplay conflict doesn’t need to have goals as high and heady as “correcting flawed mentality.” Games can make simple goals, like the desire for more resources or a higher social image, into engaging nonviolent conflicts. In fact, Animal Crossing: New Horizons created engaging gameplay with the core goals of obtaining more resources and improving one’s social image.

Animal Crossing: New Horizons has players create a player avatar before moving to a deserted island and encountering the enterprising Tom Nook– a nonplayble character (NPC). After some initial setup, Tom Nook gives the title of “Island Representative” to players and places them in charge of the development of the island. From that point on, players can work towards a number of goals, such as developing their home by signing on to increasingly large home loans, creating a bustling community by inviting non-playable characters to live on their island, filling out the island’s museum, or working on beautifying the island.

Beautify your island however you want: plant flowers, trees, or landscape.

No matter what goals players work towards, the way they fulfill those goals are completely self-motivated. If players want to create furniture to beautify their house, they can gather the proper materials from the trees, rocks, and other natural resources around their island. If players want to repay their home loans as fast as possible, they can work on developing their turnip economy. And if players want a bustling community filled with animal friends, they can talk to potential friends on islands the game creates. The game allows players to engage with whatever goals they want to.

New Horizons might seem like a boring video game. That couldn’t be further from the truth and that’s because the game lets players create their own goals. Personally, I wanted to have a perfectly organized island with a sharp aesthetic, so I spent a sizable amount of time planning out where to put all of the shops on my island, where my villagers should live, and where to put my fruit trees. I find planning and executing grand aesthetic ideas viscerally satisfying. But other people might not find that as interesting as I do. Thankfully, there are so many other systems for those players to engage with. No matter what goal players work towards, players will be able to engage with the activities they enjoy doing.

After a few hours, New Horizons starts pushing players to explore as many of the game’s systems as possible. When players build the resident services building, Tom Nook mentions that he wants to bring the famed musician K.K. Slider to play a concert. To do that, players need to bring their island’s image to a certain level. There are many ways to improve an island’s image, cleaning up weeds across the island, maxing out the island’s inhabitants, planting flowers and trees, and placing proper decorations across the island are just a few of the possible ways players can improve their island’s image. There’s no exact science to improving an island’s image, so players can usually do it by whatever means they want to.

Your neighbors will check in on your progress and even donate some items to help spruce up your island.

The key lesson New Horizons teaches about nonviolent conflict comes back to the idea of players engaging with whatever they like doing. When players work on accomplishing goals they made for themselves by means they find enjoyable, they’ll have trouble tearing themselves away because they’ll always keep creating new goals for themselves.

The Witness and Animal Crossing: New Horizons both demonstrate that games don’t need violence to create engaging conflicts. Video games don’t need to pit agent against agent to create engaging conflicts. Conflict in games can be the journey of players to improve different parts of themselves or even self-created. Video game conflict can be more than competitive violent conflict.

Dr. Rebecca Richards (St. Olaf College, Northfield, Minnesota) curates Thoughtful Play.

If you’re interested in creating your own project for Thoughtful play, contact thoughtfulplay@stolaf.edu.