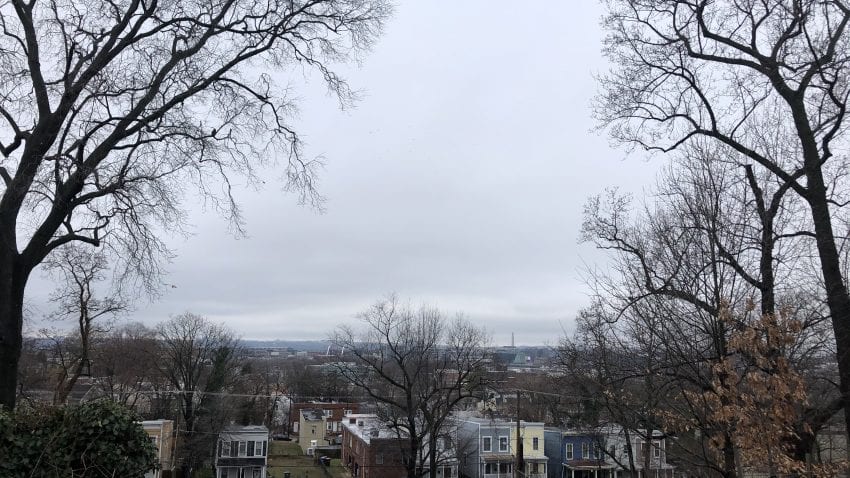

The view from Frederick Douglass’ front yard in Anacostia. The Washington Monument can be seen in the distance.

My high school psychology teacher Mr. Woodard used to tell us to question anything that claimed to be a “magic bullet” solution to a complex problem. It made sense at the time — how could any easy fix possibly consider and account for all the possible side effects within a changing and unpredictable world? However, I don’t think I truly grasped the full implications of his warning until this trip.

News of some sort is almost always on the TV as white noise when I’m home in Spokane. It’s easy to catch the tailend of a story, play pundit, and prescribe policy from the couch, convinced that my solution is not only obvious, but fool-proof. It’s easy to think that the answers to social problems are clear, if only those in power could be a little more logical or a little more compassionate. This class has taught me that it’s a lot more complicated than that.

Real projects don’t exist inside a vacuum. When the surrounding context of a policy isn’t considered, even the most well-intentioned plans can have unforeseen consequences. We saw ample evidence of this during our time in DC. On the Attucks Adams tour, our guide described the way the arrival of the Metro line compounded the damage done to the Shaw area in the 1968 riots. The economic traffic that the Metro could bring in was deeply needed, but the construction of the line made the shops along U Street inaccessible to customers, crippling the very businesses that the Metro could have helped the most. Only three of the original black owned businesses survive today. At the Anacostia Community Museum, there is an exhibit about the way the desegregation of DC schools in the 1950’s triggered white flight to the suburbs, changing demographics rather than creating meaningful integration.

Similarly damaging byproducts can be seen in the city’s ongoing urban renewal projects. Efforts to “reinvest” in areas cause them to be more desirable, driving up rent and pricing out the local community. A 2019 study found that gentrification is displacing low-income residents in DC at one of the highest rates in the nation. I was surprised to find out how large the role of the arts is in these forces. Tim Wright expressed concerns that the city-sponsored murals commemorating the artists and history of DC’s “Black Broadway” did more to appeal to the aesthetics of the incoming white population than actually support the original community. Additionally, when we met with Aisha White at Halcyon Arts Lab, someone asked why they chose to be based in Georgetown, an affluent, largely white area of DC. White explained that the organization was gifted the buildings, but she also said, “the fact is, if we were anywhere else we would probably gentrify it.” We certainly saw evidence of this trend in the areas around other arts centers we visited like Studio Theater, Atlas, Arena Stage, and Dance Place. As a class of avid arts appreciators, it was a difficult realization to see how the success of a performing arts space is not necessarily an unqualified good.

In addition, we saw the ways well-meaning policies can fail to fully realize their goals. At the National Gallery of Art, the Folger Shakespeare Library, and the Phillips Collection, there is a tangible disparity between the ideals of accessibility they claim to promote and the reality of the exclusive environment they create. Several curators we met with discussed the impossibility of designing a truly representative gallery. During our Arts Access panel at the Kennedy Center, Betty Seigel stressed that creating accessible programming is one thing, but getting people to come is another.

It has been somewhat disheartening to see how tangled up the knots of social issues are – how a hapless do-gooder can snip a single thread and unravel structures they never intended to touch. The way I see it, the only way to know where to start untying is to listen to the people that are actually embedded in the fabric of your target community.

I should clarify that I don’t intend these observations to be taken as a direct criticism of DC (although the history of disconnect between the federal rule and the local population may make it a particularly apt example). I think that the repercussions of out-of-touch policy speak to larger scale issues with the way our nation solves problems.

After unloading all of that it may come as a surprise to know that I did not leave DC feeling pessimistic. Quite the contrary. Yes, the barriers to securing equity in the arts are more daunting than I thought, but I just got to spend three weeks learning from people who are devoting their lives to grappling with immensely difficult problems. They do this by letting the community they serve take the lead.

We saw inspiring examples of community oriented programming throughout our trip. Smithsonian Folklife is working with DC residents to recognize and record DC culture and promote ownership of ward identities. Washington Performing Arts provides free concerts and performances across the city, removing multiple barriers of participation. They also empower community members to create art themselves through their Gospel choirs and the DC Keys program. Arena Stage responded to community requests and runs Voices of Now, a devised theater program designed to facilitate intergenerational understanding in Southwest DC. The Anacostia Arts Center serves the neighborhood as an incubator of small businesses and a venue for free arts events. Aisha White told us that the most successful programs she sees are those that get community input and involvement from the very beginning. Thinking back to the coalescence of negativity I opened this blog with, it is both sobering and inspiring to imagine how things may have been different if it had occurred to those making the plans to consult with those whose lives would be affected.

I think this is a crucial lesson for both academics and politicians to learn. Whether on the Hill or Capitol Hill, a theoretical understanding of an issue is not enough to properly address it. In order to make real strides in increasing arts access and social equity more broadly, we need to be better listeners and defer more of the decision-making to community members. (I’m trying really hard not to be hypocritical and offer my own “magic bullet” solution, but I’m really advocating for a change of mindset rather than a specific fix, so I think I’m off the hook.) This has been an interesting shift in my own values. Typically in civics discussions I lean toward a strong central government, but seeing the ways local organizations can specifically curate for and empower their immediate audience has given me a newfound appreciation for federalism. I’ve come to deeply respect the way the NEA disperses much of their funding to the states when they would be well within their power to dictate the use of every dollar.

I said it has been disheartening to see just how tangled up everything is – how easy it is to make a mess of things. But messy as it may be, it has been reassuring to see how the arts are tightly woven into that imperfect tapestry, especially considering that this connection is what gives the arts their power. Community-based problem solving is dependent on opening up lines of dialogue and cooperation. Our experiences at the WPA MLK concert and District Community Playback theater are testaments to the fact that few things are better at bringing people together than the arts.

I don’t want a career in the arts, and I certainly don’t want a career in politics, but I think this trip has reaffirmed that I need both in my life. There are too many ugly things in the world not to do something about it, and there are too many beautiful things in the world not to take them all in. After my time in DC, I feel better equipped to do both in a more evaluative, optimistic, community-oriented way. I make no promises to give up my prime time slot talking back to NBC, but I think my commentary will be more questions than commands from now on.