Below, are two essays from the Asian Studies and the Religion Department, “Religions of China and Japan,” 256. The first assignment, showcasing an exploration of Chinese philosophies, underscores the values of a rigid and Confucian inspired belief system, which appealed to my senses because of its belief in a single truth, similar to monotheism. The second assignment describes the difficulty of losing a national identity and that society’s reaction to it. In sum, this class and its assignments such as these has made me realize the importance of national identity and a common belief system, especially in the context of Asia.

Commentary of Xunzi – Subchapter 21, “Undoing Fixation”

Xunzi, a Confucian defender who believes in law and order and the preservation of rituals, comes across as the Chinese philosopher withholding the most concrete ideals to attain moral perfection besides Kong Zi. As a cautious optimist, Xunzi believes that human nature is bad, but attaining moral perfection through the Way is necessary, possible, and the desired result. Compared to prior philosophers, Xunzi takes the strongest stand, that a single truth and moral perfection exist. While there are various important topics to cover in Xunzi’s text, sub-chapter twenty-one presents a few of Xunzi’s most pressing arguments. In this sub-chapter, Xunzi begins by diagnosing the problem as human nature and uses various examples to defend his position that moral perfection through the Way is the ideal state for human beings.

Xunzi refutes the utilitarian-minded philosopher, Mozi, for directing his efforts on being hasty and fixated on efficiency. Xunzi claims that when the “true Way” and “Virtue” are abandoned, chaos precipitates (Ivanhoe and Van Norden 286). Xunzi, who is focused on building a highly moral society based on order, high morals, and virtue, views Mozi as poisoning the Way’s actual intent. He claims that “Mozi was fixated on the useful and did not understand the value of good form” (287). This argument can be attributed to Mozi’s defense of eliminating rituals such as a funeral because he claimed that they would “greatly [diminish] the chances for men and women to procreate” (83). Xunzi views non-action like this as a despicable practice because humans have the capacity to ameliorate their morals. He claims “that good things are achieved only through the wei, “deliberate effort”; Mozi’s position that non-action is good is in stark contrast to how Xunzi believes moral perfection is attained (255). For Xunzi, non-action is just another form of fixation, which could be defined as narrowness or a dislike of something. In Mozi’s case, non-action replaces funerals because he views them as time consuming practices that take away from ensuring that there are enough humans in society. In making his case, Xunzi uses repetition to convey statements that use antithesis. For instance, he argues that “one can be fixated on desires, or one can be fixated on dislikes” and “one can be fixated on origins, or one can be fixated on ends” (286).

While Xunzi is not directly lambasting Mozi’s beliefs in this chapter, he is repeatedly taking swift punches at individuals like Mozi, who do not follow the Way, and hold petty values that in no instance have to do with being virtuous, reflective of one’s actions, or aware of his surroundings.

Xunzi’s ideal state is one in which humans are experts of the Way and extol their human potentiality to the highest morals. Xunzi claims that the human heart must be unified and focused in order to pursue the Way; single-mindedness is key to achieving this. In Xunzi’s language, he uses an analogy based on stark imagery that follows a repetition. He describes a “farmer, is expert in regard to the fields, but cannot be made Overseer of Fields. The merchant is expert in regard to the markets, but cannot be made Overseer of Merchants. The craftsman is expert in regard to vessels, but cannot be made Overseer of Vessels” (290). Xunzi argues that while humans should have specific careers, such as being a farmer or a craftsman, there must be an overseer who leads the populace through moral guidance, or else the order of society will fall out of place. This person is “the gentleman [who] pursues the Way single-mindedly and uses it to guide and oversee things” (290). Xunzi is focused on building a world in which humans diligently work and unity, clarity, and order are initiated by moral leaders for everyone in society to adhere to.

Xunzi adds detail and organization to Kongzi’s filial and order-based society with crucial lessons for how our world should function; he strongly refutes Mozi’s lawless society for its lack of morals. Xunzi’s idea of a strictly ordered society that is held together by the accountability of moral leaders resonated with me and his direct language resonated with me because I, too, have always been a supporter of law, order, and morals. If Xunzi were to have lived in America during the past sixty years, he would have been be deeply disheartened by the frequent protests, liberation, and social movements that for many, has sown chaos. America could benefit from a leader with a strong backbone like Xunzi.

Bibliography

Ivanhoe, P. J., and Bryan W. Van Norden. Readings in Classical Chinese Philosophy. 2nd

ed. Indianapolis: Hackett Pub., 2005.

Reactions to Foreign Influence

Japan and China experienced direct foreign influence on their nations’ soil, some religious and some as a result of losing wars. After some of Japan’s and China’s citizens could no longer tolerate the deterioration of their country’s culture, both nations reached a breaking point, delivering a severe backlash, which sometimes resulted in violence. These reactions resulted in a temporary nativist ideology and outright hatred towards foreigners. These events mark a significant point in Japanese and Chinese history; that being, regardless of what nation foreign influence comes from, it will always feel like a direct assault on one’s native culture and sovereignty.

Towards the end of the Tokugawa reign in Japan, the government and samurai class faced economic hardships, which led to bitter sentiment towards Buddhism, a non-Japanese religion. This reaction provoked the Japanese to inculcate their citizenry with Shinto ideology. During the Tokugawa period, international trade flourished, but it created winners and losers; the Japanese government had begun to use debt to finance its expenses, and samurai, who had fixed incomes, suffered greatly and had to find new jobs. Criticism of foreign religion, particularly Buddhism, took hold in Japan. The beginning of criticism of Buddhism began with Hirata Atsutane, a disciple of the religious scholar Motoori Norinaga, who took on a fundamentalist belief that the “Japanese were literal descendants of Kami.” Hirata derided aspects of Buddhism and depicted callous portrayals of Buddhism as coming from India, an “inferior land” whose people “spread cow dung on the floors of their homes in order to enjoy the smell.” This damaging portrayal increasingly led to a nativist and extremely nationalistic mindset that would transform Japan, under Emperor Meiji, into a conservative society which would restore the rule of traditional native Japanese values. Shinto would become the center of the new society and “temples that combined shrines of the two religions would be purged of their Buddhist elements and made Shinto by default.” Some activists turned to violence and “…scoured the countryside beating priests, destroying temples, and plundering Buddhist treasures.” The recoil from foreign influence in the Tokugawa period created a very extreme and violent atmosphere that would eventually subside, but would indoctrinate the Japanese with an imperialistic sentiment that would strongly prevail through the end of World War II.

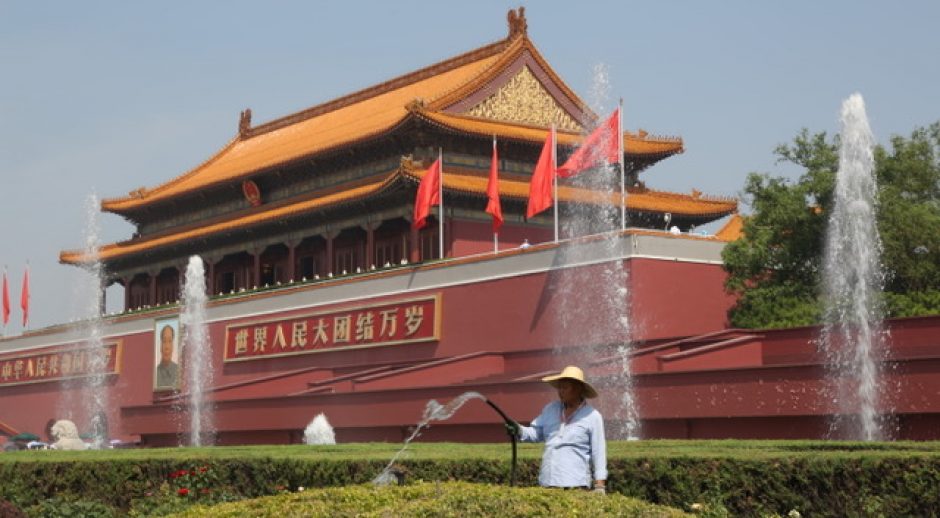

Between the end of the 19th century and until the aftermath of the Treaty of Versailles, China had lost a war with Japan and would face Western countries occupying portions of their territory. This loss of territory and power would lead to a rise in Confucian fascism. Following these events, Kang Youwei, a Confucian scholar, called for the restoration and advancement of Confucian values through the central government. Kang’s utopian vision, called the “Great Unification,” called for a world in which there would be no nations, an elected democracy, and the mixing of families, which included the mixing of sexual partners. While this would have caused the demise of the traditional Confucian value system, Confucius himself had advocated for a type of “Great Unification.” Kang’s beliefs became more mainstream and embodied the founder of the Ming Dynasty, Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang’s, religious policy, such as “his attempt to force Confucian rituals and ethics into the lives of the common people” and to solidify Confucianism as the official imperial order. Foreign involvement, both from Japan and Europe, had reinvigorated a slightly different variation of Confucianism but a native-born Chinese ideology aiming to restore aspects of Chinese culture prevailed.

While Japan’s violent retaliation against Buddhism went too far, and the proposal for a new type of Confucian living appears to be counterintuitive to building deep family bonds, nevertheless, an extreme reaction to foreign influence is understandable; Japan and China both felt threatened and sought to preserve their cultures in each of their preferred ways.