Military Intelligence Service at Fort Snelling

As early as November 1941, the War Department set up a military language school in Presidio, San Francisco, to prepare the military in decoding Japanese signals and shorthand in the likely event of conflict between Japan and the US. Accordingly, Lieutenant Colonel John Weckerling, Captain Kai Rasmussen, and Captain Joseph K. Dickey were assigned to create a language school that could train servicemen for this purpose. After recruiting and screening 1,300 Nisei (Second Generation Japanese American) on the West Coast, 58 of them were chosen to be part of the very first class. Classes started on November 3rd, 1941, taught by General Aiso, Akira Oshida, Tetsuo Imagawa, and Shigeya Kihara, and covered a core language curriculum that included reading, Japanese-to-English translation, conversation, and Japanese military terminology.

As early as November 1941, the War Department set up a military language school in Presidio, San Francisco, to prepare the military in decoding Japanese signals and shorthand in the likely event of conflict between Japan and the US. Accordingly, Lieutenant Colonel John Weckerling, Captain Kai Rasmussen, and Captain Joseph K. Dickey were assigned to create a language school that could train servicemen for this purpose. After recruiting and screening 1,300 Nisei (Second Generation Japanese American) on the West Coast, 58 of them were chosen to be part of the very first class. Classes started on November 3rd, 1941, taught by General Aiso, Akira Oshida, Tetsuo Imagawa, and Shigeya Kihara, and covered a core language curriculum that included reading, Japanese-to-English translation, conversation, and Japanese military terminology.

The War Department and the instructors initially thought that the language courses would simply be a review for those Nisei who already had knowledge of Japanese. However, they soon discovered that only a handful of the students were proficient, and they needed to develop not only a classification examination that divided the students by different levels of Japanese language proficiency but also incorporated in the curriculum topics ranging from Japanese culture to militarism. The students there studied seriously day and night, and the latrines became a popular place to work, as the lights were kept on even after hours.

After Pearl Harbor and Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, the West Coast descended into unprecedented wartime hysteria. The military language school was thus forced to move to Camp Savage in Minnesota, where anti-Japanese sentiment was not as strong, partly owing to the efforts of the then State Governor Stassen and politician Hubert Humphrey. Amid anxiety of what would happen to them and where they would go after graduating, the students continued to work hard, and the school kept expanding after its move to Camp Savage. The change of the school’s jurisdiction from the Fourth Army to the Military Intelligence Service also ushered in a name change, as it was renamed the Military Intelligence Language School (MISLS). The first class, whittled down to 40 students, graduated in the May of 1942, and 30 were dispatched to Alaska, Australia and the South Pacific, namely Guadalcanal, with 10 held back and became instructors themselves. By June 1942 Rasmussen gained permission to recruit Nisei from the internment camps, and 150 more Japanese Americans were chosen to leave the camps and join the forces.

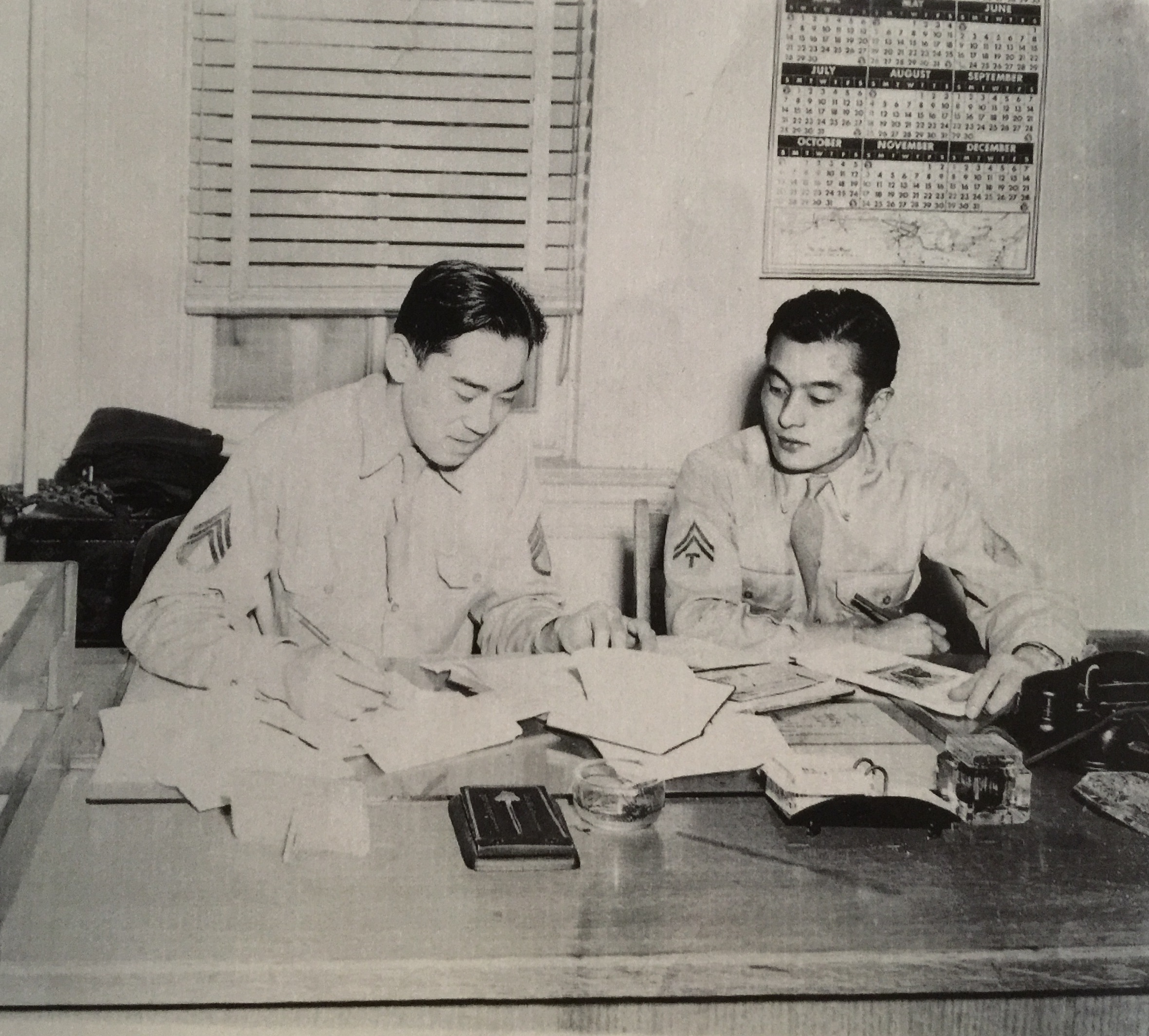

Due to suspicion of espionage, the linguists were not allowed to be sent to the front lines in the beginning and were forced to support their units from a distance. By 1943, however, the linguists’ skills became crucial in interrogating Japanese prisoners and learning from the Guadalcanal campaign. The military hence began to send them to the front lines for combat intelligence, document translation, and information collection. In 1944 the MISLS had become too large for the facilities at Camp Savage, and moved to Fort Snelling. By the time the school closed in 1946, it had trained a total number of 6,000 students, who had been deployed to the Southwest Pacific, the Central Pacific, Southeast Asia, and later in occupied Japan. Notable among them were those who served in Merrill’s Marauders in Burma. The effectiveness and willingness by which the Nisei linguists worked and served in the military paved the way for the 442nd and the success of the school was a critical beginning of diffusing suspicions on Japanese Americans’ loyalty. One of the interviewees in this project, Bill Doi, was a MISLS alumnus.

Reference

Ano, Masaharu. (1977). “Loyal linguists Nisei of WWII learned Japanese in Minnesota.” In Minnesota History (pp.273-287). St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press.

Kenney, Dave. (2005). Minnesota goes to war: The home front during World War II. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press.

McNaughton, James C. (2006). Nisei linguists: Japanese Americans in the Military Intelligence Service during World War II. Washington, DC: Dept. of the Army.