“There is not anything of human trial

That ever love deplored or sorrow knew

No glad fulfillment and no sad denial

Beyond the pictured truth that Shakespeare drew.”

-William Winter, inscription on wall of the Great Hall at the Folger Library

As the daughter of a Shakespeare professor, I have developed a sizable soft spot for the Bard, so I was especially excited about our visit to the Folger Theater. However, as in any play, the scene must be set before the action can begin, so here is a brief history of the institution.

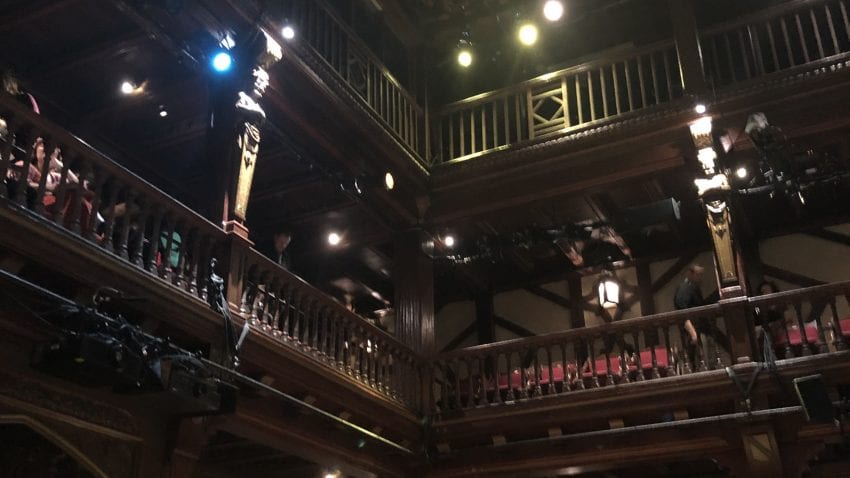

The Great Hall of the Folger Library

The theater is a part of the Folger Shakespeare Library, the largest collection of Shakespeare related texts and object in the world.The library was founded in 1932 by Emily Jordan Folger and her husband Henry Clay Folger. The couple shared a love of Shakespeare. Emily Folger earned her master’s degree in Shakespearian literature from Vassar College in 1896. She recalls her husband saying “the poet is one of our best sources, one of the wells from which we Americans draw our national thought, our faith and our hope.” The relationship between the playwright and American identity continues to be an important factor in the library’s work. Henry Folger died in 1930 but left plans for the library in his will as a “gift to the American people.” Emily Folger contributed $3 million of her assets to get the project off the ground. A central feature of the library building is an Elizabethan style theater. It was designed as a composite of multiple Elizabethan theaters, such as the Fortune Playhouse and the Globe, in order to give visitors a general impression of theaters during the era. A New York Times review from 1932 reads “[The Folger boasts] a reconstruction of an Elizabethan playhouse stunningly contrived to stage plays with the old atmosphere but with all modern appliances.” After spending an evening in the theater watching the Merry Wives of Windsor, I can’t help but agree with the Times’ assessment.

Elizabethan style tiered balconies and carved woodwork provided ample ambiance.

The front of the theater was transformed into the set of a 1970s sitcom.

Interestingly, the theater was not primarily used for plays until the 1970s. Other than a 1949 production of Julius Caesar, the stage mostly hosted lectures and speakers throughout its first decades. In 1970, the woodwork was fireproofed, and the theater received licensure to put on commercial productions. Since then, the Folger has staged more than half the plays in Shakespeare’s First Folio, in addition to works by other early modern playwrights. They also perform Shakespeare-related plays like Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead and Melissa Arctic, a 2004 retelling of the Winter’s Tale set in Minnesota. Live theater is admittedly not the focus at the Folger. It is just one of a myriad of ways the institution works to preserve and promote the legacy and works of Shakespeare. Their website lists three action statements as the guiding force of their efforts.

- “We create experiences.” The Folger puts on professional theater productions, lectures, concerts and events.

- “We transform education.” The Folger is working on revamping the way Shakespeare is taught in schools by training teachers and writing new cirriculum.

- “We drive discovery.” The Folger considers itself a center for the Shakespeare scholarship and the study of the early modern period. They facilitate research by helping scholars use their archives and cooperating with other institutions.

Going into our panel, I was curious how the diversity of its mission would be reflected in the organization. Up until that point, most of our site visits had been more narrowly concentrated on getting the populace direct access to visual and performing arts. During our time at the Folger we met with Beth Emelson, Associate Director of Public Programs and Associate Artistic Producer; Emma Poltrack, Public Programs Assistant; and Elizabeth Debold, Assistant Curator of Collections. They discussed the ways that Shakespeare’s plays are a “social art form” in the sense that the minimal stage directions and complexity of themes allow modern directors to highlight different issues and interpretations within the original text. There was also a strong emphasis on the universality of his depiction of humanity; one panelist argued that watching others’ stories “can’t help but open you up” despite 400 years separating us from their composition. Finding and highlighting the kernels of truth about the human condition is one of the Folger theater’s main strategies for making Shakespeare relevant to modern audiences. They also spoke about their efforts to connect with the community by casting actors that are representative of DC’s diversity.

The Folger’s production of Merry Wives used retro music and visual humor to bridge the gap between the audience and the original text.

I was lucky enough to be seated between my pals Claire Strother and Charles Hamer. We had a very merry time.

Another panelist described libraries as “the center of democracy” in terms of the importance of equal access to information. While their commitment to this idea is reflected in many of their educational programs, I wonder if there is more the Folger could be doing to break down perceived barriers about the elitism of Shakespeare. Much of the archival side of things felt reserved for those in academia. At the same time, our visit to the Folger was an important reminder that not every organization can fill every need. For the sake of posterity, it makes sense if preservation of the materials needs to be the priority. It is ultimately probably better for arts to institutions divide and conquer, accomplishing their individual missions to a degree that would be impossible if their resources were spread any thinner. Then again, when Elijah Leer and I met with Ethan Henderson, Ole alum and rare books curator at Georgetown, he let us handle the university’s one and only copy of Shakespeare’s first folio (for context the Folger has 82 copies and there are 235 in existence). Being able to physically turn the pages was a thrilling and infinitely more meaningful experience than looking through a glass case, as the folio was displayed at the Folger. One last element that stuck out to me during our discussion was the idea that Shakespeare is “uniquely important to the United States as a foundational document.” This picks up on some of the questions I was toying with in my pre-flection about the bilateral influence of government and art. In what ways has the language of Shakespeare shaped American society over the last 200 years? How does his place in the canon of American education reinforce certain values? Could Folger’s “transformed” education plan change which values are instilled? There is clearly more research to be done, but let’s just hope all’s well that ends well.

https://www.folger.edu/about-folger-theatre https://www.folger.edu/about https://folgerpedia.folger.edu/Timeline_of_the_Folger_Shakespeare_Library?_ga=2.173207584.2051763437.1579299793-531966387.1578964904

alternate blog titles courtesy of Elijah Leer:

The Folger doth protest too much methinks

If libraries be the food of art, read this post

A Midwinter Afternoon’s Waking Hours