Personal Memories vs. Governmental Projects

A reading route prepared by Serena (FLAC), Xiaoping, Mengxi, Katy

Throughout the novel, the government promises they won’t change places, but the pressure for modernization results in frequent change in Taipei. Changes such as the relocation or removal of trees for the sake of public projects seem to be the most offensive of these. Thus, while our narrator has a strong dislike of change in general, these changes in particular seem to interfere with her memories. As the places she loves disappear, she feels rootless and restricted to a smaller and smaller area that remains more or less unchanged.

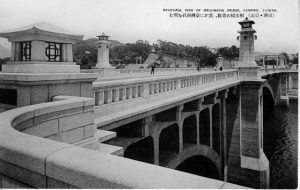

Image: Jinshui Road near Taipei

“Is it possible that none of your memories count? … Back then, before commercial real estate had led to an unrestrained opening of new roads, a building boom, and land speculation, trees could survive and grow tall and green, like those in tropical rain forests.” (E111)

“难道,你的记忆都不算数?… 那时候的树,也因土地尚未商品化,没大肆开路竞建炒地皮,而得因存活的特别高大特别绿,像赤道雨林的国家。” (S133)

[/et_pb_vertical_timeline_item][et_pb_vertical_timeline_item title=”Stop 2″ use_read_more=”off” animation=”off” text_font_select=”default” text_font=”||||” headings_font_select=”default” headings_font=”||||” use_border_color=”off” border_style=”solid”]

“One of these days, the houses in these lanes and alleys would be returned, at a high efficiency rate, to the new administration, which also loved Taiwan, to build, with plenty of corners cut, a dormitory for the Postal Administration or for the Customs Office or for professors at such-and-such university, or residences for government officials… By then, except for Lane 52 of Wenzhou Street, any other street you’d trod would have disappeared, and you’d have no place to walk, no memory to recall.” (E156)

“有朝一日,这些人家巷弄将被也爱台湾的新朝政府给有效率的收回产权并建成偷工减料的邮政宿舍、海关宿舍、X X 大学教师宿舍、首长宿舍⋯⋯,就如同除了五二巷以外的温州街曾经的每一条巷弄,届时你将再无路可走,无回忆可依凭。” (S164)

[/et_pb_vertical_timeline_item][et_pb_vertical_timeline_item title=”Stop 3″ use_read_more=”off” animation=”off” text_font_select=”default” text_font=”||||” headings_font_select=”default” headings_font=”||||” use_border_color=”off” border_style=”solid”]

When you walked by your green wall one day you discovered – oh my god – the century-old nightshade trees had disappeared overnight, all for the ostensibly justifiable reason of widening the street. You were so grief-stricken, so distressed, you felt as if you’d lost your best friend.” (E149)

“当有一日你路过你们的绿色城墙,发现天啊那些百年茄冬又因为理直气壮的开路理由一夕不见,你忽然大恸沮丧如同失了好友。” (S159)

[/et_pb_vertical_timeline_item][et_pb_vertical_timeline_item title=”Stop 4″ use_read_more=”off” animation=”off” text_font_select=”default” text_font=”||||” headings_font_select=”default” headings_font=”||||” use_border_color=”off” border_style=”solid”]

“Except for the one route that was indispensable in your daily life, you had become reluctant to roam, afraid of discovering more things like the disappearance of a line of century-old nightshade trees, afraid to face the overnight disappearance of old 30-foot maple trees on which sparrows and emerald eyes perched the year round. The latter had been replaced by a gigantic billboard, selling upscale housing 100,000 NT a square foot. Directly across from it, in Lane 243, Jinhua Street, a row of 50-year-old eucalyptus trees had been taken down by his Excellency the Mayor, who never stopped crowing about how much he loved this island and this city. Even more ironic was that the place was immediately turned into a small community park with tiny trees.” (E152-153)

“这样的经验,愈来愈珍惜了,除了平日不得不的生活动线,你变得不愿意乱跑,害怕发现类似整排百年茄冬不见的事,害怕发现一年到头住满了麻雀和绿锈眼的三十尺的老槭树一夕不见。立了好大看板,买起一坪六十万以上名门宅第,它正对的金华街二四三巷一列五十年以上的桉树也给口口声声爱这岛爱这城的市长大人砍了,并很讽刺的当场建了个种满小树的社区小公园。你再也不愿意走过这些陌生的街巷,如此,你能走的路愈来愈少了。” (S162)

[/et_pb_vertical_timeline_item][et_pb_vertical_timeline_item title=”Stop 5″ use_read_more=”off” animation=”off” text_font_select=”default” text_font=”||||” headings_font_select=”default” headings_font=”||||” use_border_color=”off” border_style=”solid”]

“Over half the sweet gum trees, which had been as old as Chokushi Street, were gone; the beautiful Miyanoshita Road had grown into such a state that it was like countless incurable tumors-ugly, ugly. Mournfully, you avoided the area, but what had died of course, included part of you.” (E160)

“与敕使街道同年岁的枫香不见了大半,美丽的宫ノ下参道变成长了无数肿瘤群医束手的景象,丑透了,你带着哀悼的心情走避,死去的,当然包括你的一部分。” (S167)

[/et_pb_vertical_timeline_item] [/et_pb_vertical_timeline]

Note 1

To begin the entire novella, the narrator asks the question of whether any of her memories count. This question is then connected with seven different observations about the world, during an unspecified time period called “back then.” In each, she emphasizes that “back then” was better. It seems that “back then” is superior in terms of its bluer sky, the resilience of young bodies, the health of forests, the lack of public spaces for young people to roam, the night sky, and the classic American background music. A repeating theme in the book is the linkage of memories to natural and historical spaces. The removal of trees and forests for the sake of human constructions represents an antagonism to people’s memories.

Note 2

The narrator’s voice loudly conveys distrust of the government to preserve her memories. New public projects that seem to be done in the name of “love” for Taiwan simply end up taking private land and destroying it with shoddy construction. Thus, the appearance of governmental progress is utilized as a power play to cut corners. It seems to the narrator that all the places that are important to her, except for Lane 52 of Wenzhou Street, have disappeared along with her memories of those places. Furthermore, ‘依凭’ translates most accurately as ‘to depend on, rely on, or lean against.” The translation of the Mandarin phrase “无回忆可依凭,” may be more accurately translated as “without memories to rely upon.”

Note 3

The author uses exaggeration when she compares her sadness over the loss of the nightshade trees to the loss of best friends; however, the exaggeration conveys the author’s love of how Taipei used to be. Nightshade trees became part of author’s memory of the old Taipei, and in the narrator’s perspective, widening the street should not be a good reason to destroy the scene of her youth.

Note 4

As an old soul, You loves her old memories of Taiwan’s environment, including in nightshade trees, maple trees, and eucalyptus trees. Some of them were replaced by upscale housing and a community park that designed by the hypocritical mayor. As all the changes happen, the narrator feels that she has grown unfamiliar with places that use to be part of her.Without all the familiar objects and places, she feels her memories fading away.

Note 5

The narrator sees the sweet gum trees and Miyanoshita Road as integral figures that played a huge part in her youth and cherished memories. Although the narrator does not go into much detail, the fact that part of the narrator dies demonstrates the strong connection the narrator had with the gum trees and Miyanoshita Road, whether it be physical, emotional and/or symbolic connections. In contrast, the government does not see the gum trees nor Miyanoshita Road as having any kind of special memory associated with a particular someone but rather “things” that can be taken away or changed primarily for profit. The narrator also uses words that possess negative connotations (mournfully, incurable, tumors, ugly), conveying to the readers that the change is highly undesirable and so gut-wrenching that she goes out of her way solely to avoid the area. In short, if trees and other plants can easily be replaced with commercial businesses and corporate buildings that will attract people and bring in more income, the government has no problem with removing anything that gets in the way of their plans thus destroying personal memories one by one.

Image Credit: 明治橋の美觀、遙かに臺灣神社を望む

Image Credit: Leah Suffern