Classical Chinese Quotes and Imitations

A reading route prepared by Can, Ge (FLAC only)

Images (left): flags of Koxinga and Qing

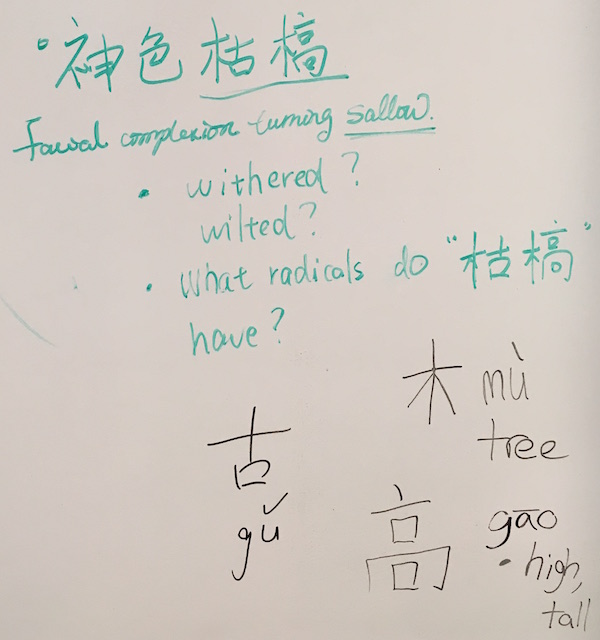

不得不令人想到天人五衰,耳不聪,目不明,嗅觉不灵,神色枯槁,连华美的衣裳也蒙尘埃。

因为不肯承认耳不聪目不明,于是投票日次日的那个额外假日,你决定独自去一趟白天的足球场,因为非常惊恸如何可能想不起原先那是哪里,尽管你长年居住城东,二十年来未曾须臾离开过此海岛。(p148)

You couldn’t help but think of the five failing of a deity: ears turning deaf, eyes going blind, nose getting dull, facial complexion turning sallow, splendid clothes covered in dust.

Refusing to admit that your ears were turning deaf or your eyes going blind, you decide to go alone to the football stadium on the post election holiday, in the daytime, for you were shocked and distressed to be unable to recall what had originally been at the site, even though you’d spent most of your life in the city’s eastern district and hadn’t been off the island for a single moment over the past twenty years. (p133)

[/et_pb_vertical_timeline_item] [/et_pb_vertical_timeline][et_pb_vertical_timeline admin_label=”Timeline – Vertical” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid” background_image=”https://pages.stolaf.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/946/2017/03/tao.jpg”] [et_pb_vertical_timeline_item title=”Stop 2 ” use_read_more=”off” animation=”off” text_font_select=”default” text_font=”||||” headings_font_select=”default” headings_font=”||||” use_border_color=”off” border_style=”solid” background_image=”https://pages.stolaf.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/946/2017/03/tao.jpg”]

车速以时速一百公里冲越关渡宫隘口,大江就横现眼前,每次你们都非常感动或深深吸口河海空气对初次来的游伴说:“看像不像长江?”

车过竹围,若值黄昏,落日从观音山那头连着江面波光直射照眼,那长满了黄槿和红树林的沙洲,以及栖于期间的小白鹭牛背鹭夜鹭,便就让人想起“晴川历历汉阳树,芳草萋萋鹦鹉洲”。

Traveling sixty miles an hour, the bus would roar through Guandu Temple Pass, where the wide river appeared before you, and each time you would be deeply moved, or you would breath in the damp river and ocean air before saying to your companion, who was seeing it for the first time, “Doesn’t that look like the Yangtze River?”

When the bus passed Zhuwei in the afternoon, the setting sun would send its rays across the rippling surface from the Guanyin Mountains on the opposite bank. Sand-bars overgrown with yellow hibiscuses and mangroves, as well as the small egrets, buffalo herons, and night herons perched on them, would call to mind the lines “Clear Streams meander through the Hanyang Woods/ Fragrant grasses spread across Parrot Islet.” (p114)

[/et_pb_vertical_timeline_item] [/et_pb_vertical_timeline][et_pb_vertical_timeline admin_label=”Timeline – Vertical” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid” background_color=”#ffffff” background_image=”https://pages.stolaf.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/946/2017/03/taipei-food-.jpg”] [et_pb_vertical_timeline_item title=”Stop 3″ use_read_more=”off” animation=”off” text_font_select=”default” text_font=”||||” headings_font_select=”default” headings_font=”||||” use_border_color=”off” border_style=”solid”]

感觉有一点秋天味道的时候,你们便只乘到宫ノ下駅下车,搭公车的话便到剑谭——剑谭在北淡大浪泵社二里许,番划艋胛以入,水甚阔,有树名茄冬,高耸障天,大可树抱,崎于潭岸,相传荷兰人插剑于树,生皮合剑在其内,因以为名。(p144)

When there was a hint of fall in the air, you’d get off the train at Miyanoshita Station, or Jiantan if you were taking the bus- Jiantan was less than hald a mile form Dalang benghse at the northern end of the Tamsui River, where the natives rowed thier boats in and the Channel was wide. A tree called the nightshade was so tall it blocked out the sun, so big it required several linked arms to encircle its trunk. It grew by the lakeshore. A Dutchman was rumored to have stuck his sword into the tree, which grew around it; that’s how the place got its name, Jiantan- Sword Lake.

[/et_pb_vertical_timeline_item] [/et_pb_vertical_timeline][et_pb_vertical_timeline admin_label=”Timeline – Vertical” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid” background_image=”https://pages.stolaf.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/946/2017/03/taipei-caifeng.jpg”] [et_pb_vertical_timeline_item title=”Stop 4″ use_read_more=”off” animation=”off” text_font_select=”default” text_font=”||||” headings_font_select=”default” headings_font=”||||” use_border_color=”off” border_style=”solid”]

其后十年,日人拆城。

梦境一样的北势湖,再也没去过的北势湖。(p158)

Japan tore down the city wall ten years after the Qing built it.

You never returned to Beishihu, dreamlike Beishihu. (p147)

[/et_pb_vertical_timeline_item] [/et_pb_vertical_timeline]

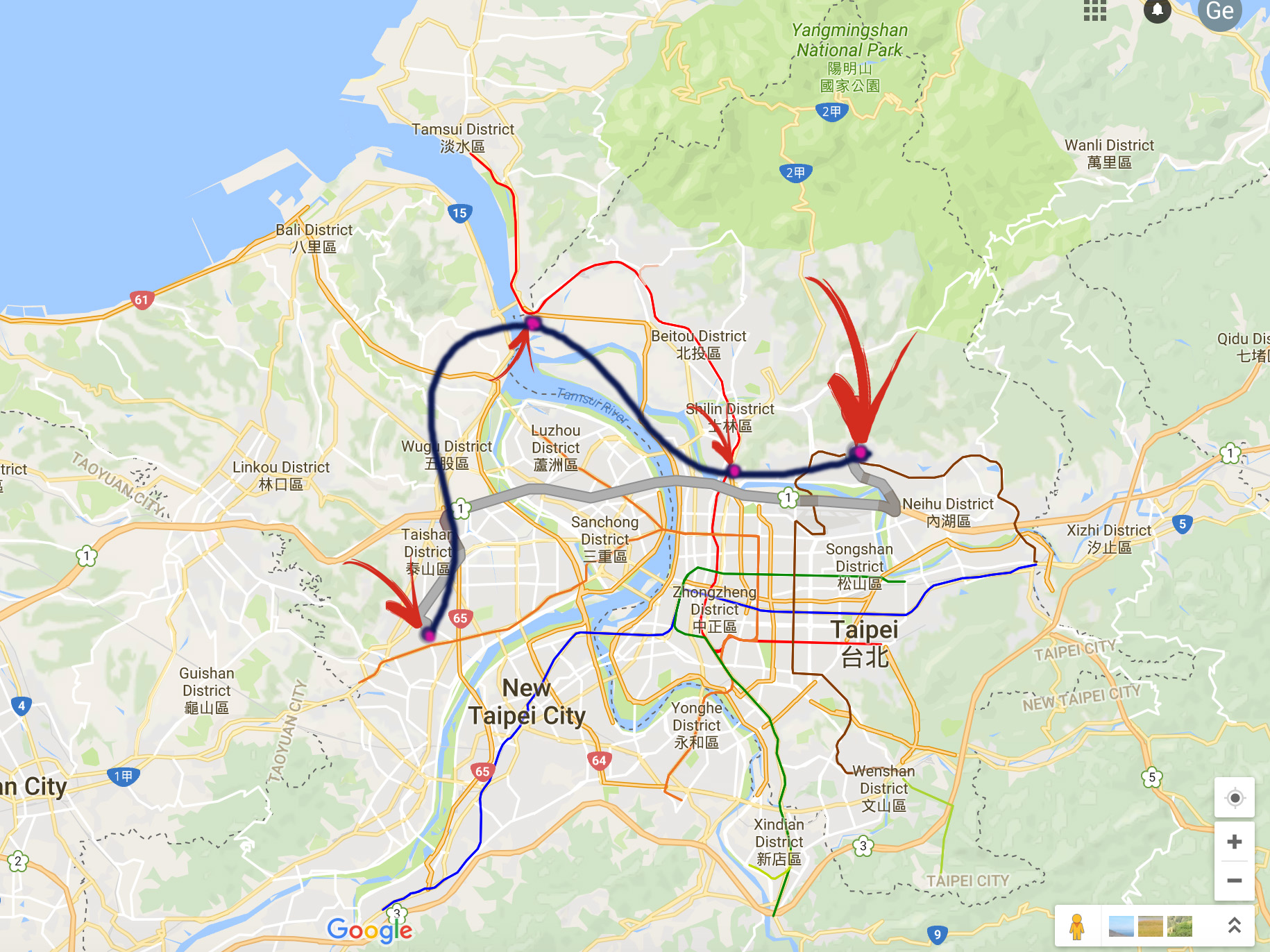

Map of locations mentioned in the quotes

From left to right :

- Football field

- Guandu Temple Pass

- Jiantan

- Beishi Lake

Stop 1

The concept of “天人五衰” five failing of a deity is from buddhism, which are five signs of the decay of a deity. In buddhism, the first sign is the flowery crown withered, the second sign is that the sweat pours from the armpits, the third sign is that the robe turns soiled, the fourth sign is losing self-awareness or become dissatisfied and the last sign is that their bodies become fetid. It is a process of being aged and decay. Here, the author specifies the five signs as “ears turning deaf, eyes going blind, nose getting dull, facial complexion turning sallow, splendid clothes covered in dust”. The author uses “天人五衰” to respond to the inevitable aging and growing powerlessness indicated in the previous passages (“fading smell”, “past twenty years” and so on). The style of writing, “耳不聪,目不明,嗅觉不灵, 神色枯槁,连华美的衣裳也蒙尘埃”, is very similar to classical Chinese writings (…不…, …不…, …不…). The use of imitation of classical Chinese here increases the reliability of the author’s explanation of “five signs” (since it sounds like quoting from a real classic work).

Stop 2

“晴川历历汉阳树,芳草萋萋鹦鹉洲” is from a classic (and famous) Chinese poem Yello Crane Tower (《黄鹤楼》) by Cui Hao 崔颢 (d. 754). The complete poem is:

黃鶴樓 – 崔顥

昔 人 已 乘 黃 鶴 去 , 此 地 空 餘 黃 鶴 樓 。

黃 鶴 一 去 不 復 返 , 白 雲 千 載 空 悠 悠 。

晴 川 歷 歷 漢 陽 樹 , 芳 草 萋 萋 鸚 鵡 洲 。

日 暮 鄉 關 何 處 是 , 煙 波 江 上 使 人 愁 。

The poem begins with four sentences that talk about the lost of the beautiful old days. But in next two sentences, “晴川歷歷漢陽樹, 芳草萋萋鸚鵡洲”, the poet painted a very different picture. “晴川”, “漢陽樹”, “芳草” and “鸚鵡洲” are things the poet saw at that moment. The poet also used “晴” (bright),”歷歷” (clear),”芳” (aromatic),and “萋萋” (prosperous) to show a clean, peaceful image now. However, after this sentence, the poet went back to the lost feeling again. But this time, this lost feeling comes from the uncertainty of the future. Everything that the poet saw at the time, the “apparent bright and clear view”, forms a sharp contrast of both the nostalgia for the good old days and the “foggy, uncertain future”.

It is quite interesting that the author of The Old Capital choose to quote “晴川歷歷漢陽樹, 芳草萋萋鸚鵡洲” here. It clear relates to the previous sentences where the author describes a few peaceful, pleasing scenes – the setting sun, the rippling surface, yellow hibiscuses and mangroves and so on. But if we read carefully, we can probably feel the nostalgia when the author mentions “the Yangtze River”. Unfortunately, although the English translation sort of render the meaning of the text to the reader, it hardly delivers the slight melancholy that indicated in the book even with the context.

Stop 3

“北淡大浪泵社二里许, 番划艋胛以入,水甚阔,有树名茄冬,高耸障天,大可树抱,崎于潭岸,相传荷兰人插剑于树,生皮合剑在其内,因以为名” – from《重修台湾府志》, written by Xian Fan (范咸), Qing Dynasty.

The author uses this quotation to describe the exact location, the breathtaking landscape and the story of origin of 剑谭 (Jiantan). Even though in the original text, the author does not use quotation mark to indicate that the sentence is from an traditional Chinese work (not written by the author himself), it is easy to tell that it is written in classical Chinese style (not in vernacular writings). However, the English translation completely fails to distinguish the classical Chinese from the vernacular Chinese. In the other words, by just reading the English version, you cannot tell which part is author’s quotation from the classical work and which part is not. In fact, this failure is understandable since Chinese and English are distinct (and clearly we cannot use ancient English to translate ancient Chinese). But I would recommend to use quotation marks to indicate the quotations when translating classical Chinese into English; this could help remind the readers that they are reading “classical Chinese.”

駅: yi4, 驿站

Stop 4

“其后十年,日人拆城,” with its XXXX-XXXX structure and classical diction 其后, sounds a lot like classical Chinese (or Chinese poem).

This sentence responds to the latter passage “you were so grief-stricken, so distressed, you felt as if you’d lost your best friend.” Because all the familiar things were changed. The governor sold land and tore down the old building for more profit, just like how Japan tore down the city wall ten years after the Qing built it. By imitating classical Chinese style, the narrator assumes a historian’s voice to tell the changes of the city.