Pages 178-196

A reading route prepared by Cal (FLAC), Yuwei, Jake

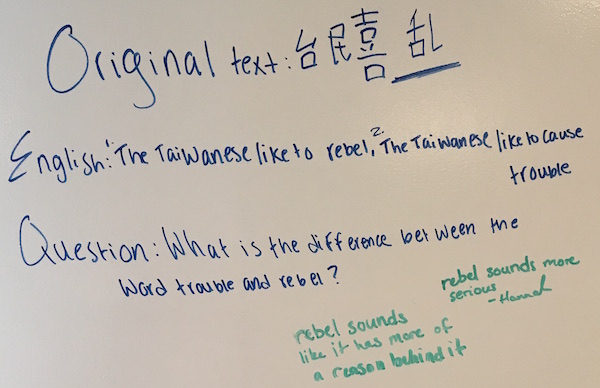

The quotations throughout the assigned pages present different variations of the Taiwanese getting into trouble. The various variations throughout the novella criticize the perspective that the Taiwanese like to rebel. Not only do the variations illustrate the Taiwanese preference to rebel but also the living following the dead in their rebellion.

Image Credit: http://allindiaroundup.com/general/why-are-insects-attracted-towards-light/

*The Taiwanese like to rebel, like moths flying into a fire, the dead followed by the living. — Once again, Dingyuan (Page 176)

台民喜乱, 如扑灯之蛾, 死者在前, 投者不已。 — 仍是蓝鼎元 (Page 179)

[/et_pb_vertical_timeline_item][et_pb_vertical_timeline_item title=”Stop 1″ use_read_more=”off” animation=”off” text_font_select=”default” text_font=”||||” headings_font_select=”default” headings_font=”||||” use_border_color=”off” border_style=”solid”]

Toward the end of the Kangxi reign, Lan Dingyuan, who led an army to put down the Zhu Yigui rebellion, said that the Taiwanese are habitually rebellious; you quell them but they rise up again […] Dissatisfaction with the place did not begin with you. You really did not want to go back there. (Page 143)

康熙末年,随军来台平朱一贵乱的蓝鼎元说:台人平居好乱,既平复起。 […] 不满那地方的,不自你始。你真不想回去呀。(Page 155)

[/et_pb_vertical_timeline_item][et_pb_vertical_timeline_item title=”Stop 2″ use_read_more=”off” animation=”off” text_font_select=”default” text_font=”||||” headings_font_select=”default” headings_font=”||||” use_border_color=”off” border_style=”solid”]

Everyone knew that the alpinia grew most abundantly in the graveyard, and that the pungent odor was a result of many years’ sucking on the marrow of the dead. (Page 181)

天知道月桃最爱长在坟地, 辛烈的气味根本就是长年吸食死人骨髓 的结果。(Page 181)

[/et_pb_vertical_timeline_item][et_pb_vertical_timeline_item title=”Stop 3″ use_read_more=”off” animation=”off” text_font_select=”default” text_font=”||||” headings_font_select=”default” headings_font=”||||” use_border_color=”off” border_style=”solid”]

That reminded you of the dissident who had been exiled for thirty years because of his resistance against the totalitarian government. That was then, this is now. Once he became the country head, reminiscent of others before him, he converted the island’s last piece of wetland into a polluting industrial site that consumed tremendous amounts of energy. How was he any different from the foreign he’d criticized and hoped to overthrow? How else would he have dared to do what he did? When you walked by your green wall one day you discovered-oh my god-the century- old nightshade tress had disappeared overnight, all for the ostensibly justifiable reasons of widening the street. You were so grief-stricken, so distressed, you felt as if you’d lost your best friend. (Page 149)

你想起那个因反抗集权政府去海外三十年不能回来的异议人士,时移事易,他一旦当上县长以后,照样把南岛最后一块湿地挪做高污染高耗能源的重工业用地。他跟他以往批判甚而欲推翻的外来政权做的一模一样。不然何以他们敢如此做呢,当有一日你路过你们的绿色城墙,发现天啊那些百年茄冬又因为理直气壮的开路理由一夕不见,你忽然大恸沮丧如同失了好友。(Page 159)

[/et_pb_vertical_timeline_item][et_pb_vertical_timeline_item title=”Stop 4″ use_read_more=”off” animation=”off” text_font_select=”default” text_font=”||||” headings_font_select=”default” headings_font=”||||” use_border_color=”off” border_style=”solid”]

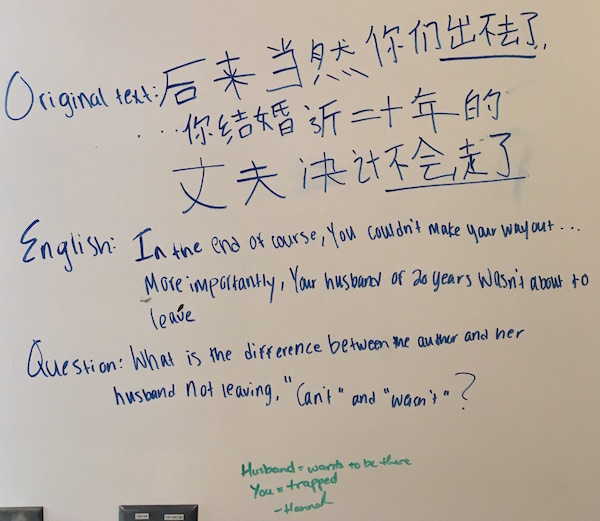

On the same evening 20 years later, you and your husband would go to a gathering purported to have been attended by 100,000 people […] Your original intention had been to donate some money, a meager contribution to help unseat the ruling party […] In the end, of course, you couldn’t make your way out through the crowd. More importantly, your husband of nearly 20 years wasn’t about to leave. When you looked at him, his blurred face displaying the same expression as the tens of thousands of faces around him, he could have been a total stranger who was shouting and clapping in response to the spotlighted speakers. (Page 132)

二十年后,同一个日子同一个晚上,你和丈夫参加一个号称十万人的聚会 […] 你本来只想去捐些款,略尽能否把执政党藉此拉下台的绵薄之力 […] 后来当然你们出不去了,最主要的,你结婚近二十年的丈夫决计不会走了,你看到他与周遭几万张模糊但表情一致的群众的脸,随着聚光灯下的演说者一阵呼喊一阵鼓掌,陌生极了。(Page 147)

[/et_pb_vertical_timeline_item][et_pb_vertical_timeline_item title=”Stop 5″ use_read_more=”off” animation=”off” text_font_select=”default” text_font=”||||” headings_font_select=”default” headings_font=”||||” use_border_color=”off” border_style=”solid”]

You woke up from a light sleep, plagued by worries of a fire breaking out. (Page 187)

在时时担心会失火的浅眠中醒来, (Page 185)

[/et_pb_vertical_timeline_item][et_pb_vertical_timeline_item title=”Discussion Question” use_read_more=”off” animation=”off” text_font_select=”default” text_font=”||||” headings_font_select=”default” headings_font=”||||” use_border_color=”off” border_style=”solid”]

How do you think about the meaning of rebellions? Is the rebellious really different from the rebelled?

[/et_pb_vertical_timeline_item] [/et_pb_vertical_timeline]

Stop 0

This quote does not view the Taiwanese very positively. They are compared to moths flying into a fire. Moreover, the original text does not use the word rebel, but rather messy. The fire represents something hot and enticing, but ends up being the thing that kills the moth. Similarly, the Taiwanese are attracted to trouble and messiness. It is hot and enticing at first, but then ends up being to their detriment. This illustrates why the dead are followed by the living. The dead are encaptured in the fire but are still followed by the living because the fire is hot and enticing.The author goes on to criticize this quote by providing examples where the Taiwanese rebel or cause trouble.

Translation Note 0 and 1

In the original text they use the word 乱, which means to cause trouble or messiness. 乱 has a more diverse meaning than does rebel. Rebel’s meaning is mostly political whereas 乱 can mean to rebel or to cause a mess.

Stop 1 Analysis

This quote takes place when the narrator finds out her identity as Japanese in Japan and becomes very dissatisfied with Taiwan, and it shows the narrator’s personal rebellion against her Taiwanese identity. In this quote, she lists the historical dissatisfaction arguments of Taiwan, especially arguments from people in Qing dynasty. This is because she is looking for people who resonate with her, who has the same dislike feeling toward Taiwan. She gets the strength for her rebellion, to deny her Taiwanese identity from these historical arguments, and also obtains kind of encouragement to embrace her Japanese identity.

Stop 2 Analysis

After the quote the narrator states that she forgets that she actually had a tomb to visit years later. It means that going to ancestors’ tombs and serving the dead rice cakes do not give her a sense of belonging to her ancestors, neither to the place of their tombs — Taiwan. Standing in front of her ancestors’ tomb, the only emotion that she has is the disgust of death (the smell of the rice cake). We can see that she is separated with her ancestors in emotion, and that’s probably one of the reasons why she becomes so doubtful of her Taiwanese identity when she gets older.

Stop 2 Translation Note

The original text uses the word 爱. By using the word 爱, it gives the plant human characteristics. It is as if they plant is choosing to grow most abundantly in the graveyard, the plant loves to grow.

For the plant’s pictures, go to 荒野新竹分会.

Stop 3 Analysis

This quote brings a very interesting phenomena: The rebellious is actually not different from the rebelled. For example, the dissident in this quote, who had been exiled for thirty years and rebelled against the totalitarian government, did the same thing that the government did when he became the country head. Then there would be new rebellions against that dissident. However, people’s living environment has never been cherished and respected. The quote questions the meaning of rebellions by showing the vicious circle of rebellions. Though there has been continuous rebellions in Taiwan, the real problems (the destruction of people’s old memories and living environment) have never been resolved.

Stop 4 Analysis

In the previous quotes, we have seen a history of Taiwanese rebellion, or “messiness.” While passages were told by You, they were not directly about her own personal experience with messiness. In this passage, however, You states her original intention for coming to the gathering at the stadium: to donate money to unseat the ruling party. This act, a quiet rejection of the status quo rather than a hope for a better ruling party, is typical of You’s personal messiness. She always keeps her own sense of self neat, yet quietly rejects the changes that are forced upon her. Her rebellious spirit is personal and private, but still hers and hers alone. However, a spark is ignited within her and her husband when surrounded by 100,000 of her peers. This point is further emphasized when she finds her husband of nearly 20 years. His face is blurred into the faces of those around him as if he were no longer one person, but a part crowd united by a rebellious fervor. You, who has a neatly and cleanly defined sense of self, finds herself and her husband messily spilled into a rebellious crowd.

Stop 4 Translation Notes

The Chinese translation says 出不去 for the author, but for her husband the original text says 不会走了. 出不去 means that author cannot get out of the crowd or Taiwan, whereas 不会走了 means that the husband is just not leaving Taiwan. The Chinese translations adds in another aspect that the English translation does not. Because the narrator is second generation immigrant, an external province person, she is not able to go back to Mainland China. Unlike her husband, who is a native Taiwanese, who is choosing not to go back.

Stop 5 Analysis

Here, it seems, that the cycle is completed. The rebellious and messy spirit of the dead consumed the living, igniting a crowd of nearly 100,000 into mass protests for change. You observes this cycle and, fearing that she too would be consumed by this fire, reclaims her own introspective and personal messiness. She rejects her “Taiwanese messiness,” instead adopting a different identity entirely, as Japanese, as a tourist in Taiwan.