PAI Hsien-yung, “A Touch of Green”

The war against Japan and the civil war are the driving factors that influence the characters’s lives. Because of their military association, the characters live in military villages like East Benevolence Village for the families of those who serve in the Republic of China’s forces. Having their husbands serve in the wars greatly impacts the wives’s lives.

Although the war takes their husbands far away into danger, the wives still seem to support their side. There is a lot of pride and ownership in the phrase “our capital” and even more in “Painted Capital of Six Dynasties fame”. They also still go by the system of counting years in terms of the government power. Shih-niang recounts the when they, as supporters of the Republic of China, had to flee for Taiwan in “the thirty-seventh year of the Republic”.

In Taiwan, the characters are relocated to another military families’s village. The particular one Shih-niang lives in is coincidently also named East Benevolence Village. The name can be a symbol of bringing familiarity to a new place. Even though the characters have been relocated, they bring familiarities like songs and food and mah-jong.

The title “A Touch of Green” is also the name of the song Shih-niang hears Verdancy sing in Taiwan. Verdancy, from verdant, means green or with growing plants, budding. In Chinese, green is a symbol of youth and naivety. We see Verdancy change from a very young and naive girl to a seemingly carefree, young woman. When Kuo Chen dies, she almost kills herself out of sadness and anger. When Junior Ku dies, also in an aircraft accident, she acts completely unaffected, still going about a game of mahjong like normal. She still has the part of her that is green, young, and wants to grasp onto the best of the moment even through life’s hardships.

YU Guangzhong, “Nostalgia”

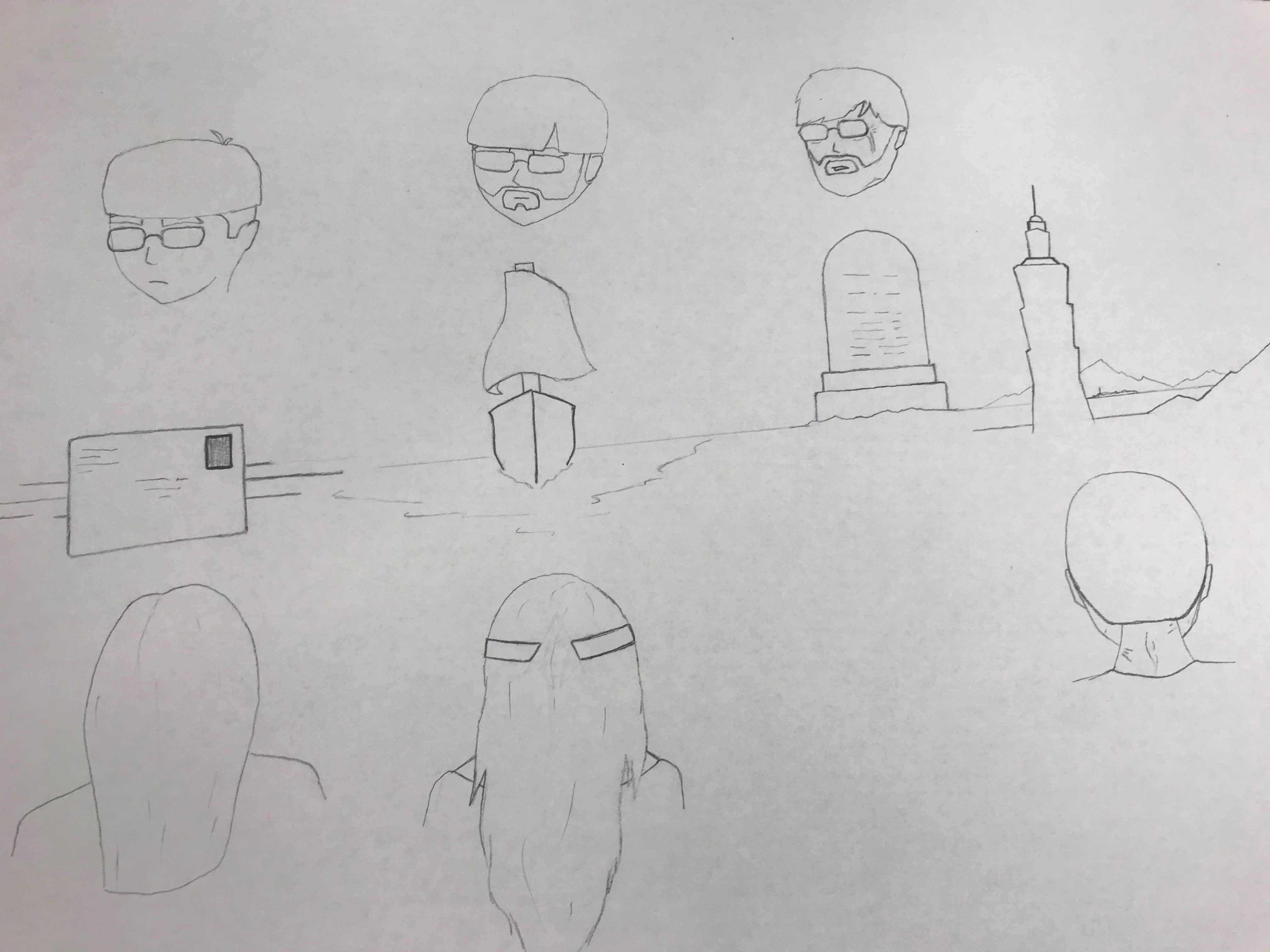

When Yu Guangzhong writes Nostalgia, it can be interpreted in a number of different

ways. He writes to illustrate his life in relation to gaps that he has crossed or wishes that he

could cross. When he writes of a small stamp, this item, while described as tiny, holds the

utmost importance, acting as the connection between him and his mother. The narrow boat

ticket, also described in minute terms, is the thing that will ultimately connect him and his wife.

The deep, deep grave shows a bit of a deviance from the way that the gaps are described in the

rest of the poem, and the interpretation of this is subjective. One explanation to offer is to

realize that the other gaps are crossable, even if difficult and defining of Yu Guangzhong’s life;

however, no matter how long he waits or whatever he does, the grave is one gap that cannot

be crosses. Finally, Yu Guangzhong described his separation from mainland China as that across

a shallow straight. While the straight isn’t actually shallow, it remains crossable. Along with this,

in the drawing, the gaps are all portrayed like the poem, using methods that make the gaps

seem small. However, when it comes to the grave, the absence of the mother shows that, there

is nothing left and the crossing of this gap is unlike any of the others. The contrast of the fact

that, despite being described as small, all of these gaps are actually quite large, is used to show

that these seemingly small things are the things that define his life. It also may be reflective of

the way in which Yu Guangzhong may be bending the truth, trying to keep a positive outlook

despite the actual events of his life.

When Yu Guangzhong writes of the gaps between himself and the things he longs for,

his emotion is seen through the sharp descriptions he uses to show that his memories, while

fittingly dramatic, are realistic and empathetic. The tombstone acts as a transition for the

poem. In his previous years, Yu Guangzhong had been separated from things, but still had the specific and important items that bridge him with what he longs for. After the tombstone, the poem shifts from things that are materially attainable to speaking of things that, while still

obtainable, are now shrouded with the same sense of distance and mysticism as death. When

Yu Guangzhong finally writes of his connection, or lack there-of, to the mainland, this is the

portion of the poem that brings all of his memories to a culmination in his modern day, selling

to the audience his situation. Him on one side, and a seemingly unobtainable homeland far off,

or not too far, based on his language, in the distance.

The picture shows this relationship in a series of images, showing Yu Guangzhong both

connected to the things from which he is apart, but also shows the sharp contrast of the things

separating him in a continuous line, illustrating that, even though his life has changed, things

have remained constant. Along with this, the last frame of the drawing depicts the ultimate

change in the poem as well, showing Yu Guangzhong on a separate side than before, looking

back, rather than ahead.

SU Weizhen, “The End of the Military Family Village”

During the Chinese Civil War that was being fought between the Republic of China and the People’s Republic of China, The Republic of China began losing ground very quickly and were forced to flee to Taiwan. From all different branches of the military, navy, army, air force, military police, and joint logistics. They lived in small villages of interconnected bungalows called a juancun with their families. They made up many different villages that were interconnected and had names like “Overcome-Challenge Theater”, and “Self-Strengthening Women’s League” when they came together and did things. These people in these villages were called second generation mainlanders. The fact that they had many neighbors but few relatives is because they all lived close together but it was in a land that was technically foreign to them.

They had no ancestral tombs there because all of their ancestors are from the mainland. As time went on there started to become many people that are actually Taiwan born, but on their ID’s it still showed they were from somewhere in the mainland. They try to be as much of a part as Taiwan as possible however. They speak more native Taiwanese dialects and languages like Mandarin, Hakka, or Taiwanese, even though in their own homes they spoke the dialects that they are more used to from the mainland. They were living in a microcosm of mainland China. However there began to be a push to develop Taiwan. There was a push to rebuild and redevelop and the bungalows of the juancun were just in the way. Many of the members of the juancun refused to leave their homes, and so many redevelopment projects were left up in the air. Most of the juancuns that people refused to vacate were just burned down instead. These people had to question where they had a home. They did not really have one in Taiwan at this point, but they did not have one in mainland China either. Should they have loyalty for their country that drove them away? They are lost and left with scars from the war, with homes and hearts that are beyond repair.

Recent Comments