When reflecting on my interim experience, I am reminded of my travels to Washington, D.C. some six years ago. In what was a rather generic tour of the city – with visits to the White House, monuments, and Smithsonian institutions – was an overwhelming introduction to the incredible access we have to the fullness of cultural history in the U.S. Fast forward to a month ago, I was a naive studio art major with a committed interest in the arts, but still completely unaware of the complexity and scope of its relationship to our democracy. Despite a deep connection to the arts and a visit to our nation’s capital, I think it’s safe to say that I could not have possibly prepared for this class. These three weeks of discussion and close examination with arts professionals, lobbyists, and elected representatives have opened up a newfound understanding of the vital role of the arts in our society.

If I had to summarize the content of this course in one phrase it would be that democracy is dependent on the arts. My first real realization of this was in our meeting with Dr. Samir Meghelli of the Anacostia Community Museum. As someone who challenged the notion of the role of museums in the community, Dr. Meghelli expressed the responsibility of voicing the needs and interests of the local community. A democracy cannot function without sensitivity to the needs of others. Art can act as that bridge between communities and government – an accelerator to legislative change. It is the arts that open our eyes to perspectives that are different from our own and thus foster a sense of empathy required for a healthy democracy. Inspired by art, empathy is the fuel that counteracts our fundamental selfishness as humans and keeps democracy alive.

This class has truly challenged my attitudes and beliefs. It has given me a chance to reflect on my character in relation to those we’ve met with. I was inspired when speaking with representatives from the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage who were emphatic about the repatriation of artifacts that were stolen from oppressed groups of people. For good reason, it surprised me that a national museum, in the business of attracting visitors through extravagant collections of artifacts, would unselfishly return what is not theirs. This is an inspiring example of how to act ethically and in good conscience no matter the opposing incentive. Similarly, Dr. Dwanadalyn Reece,

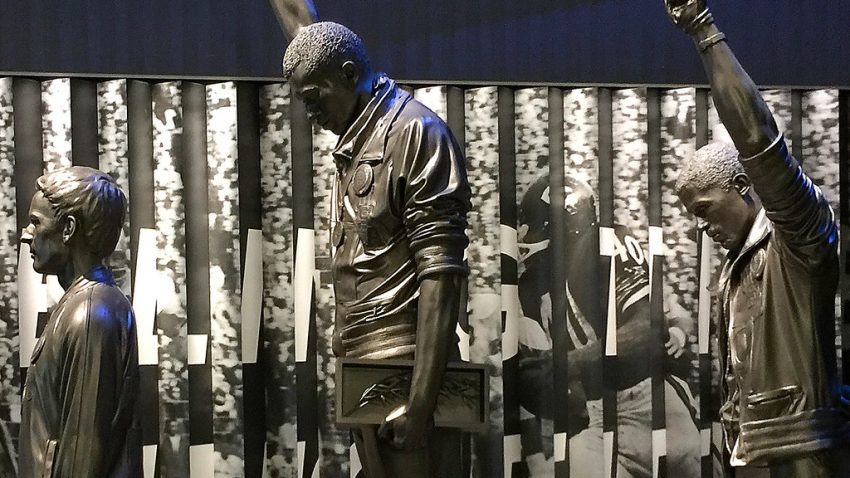

The ‘Black Power’ Salute Statue, found at the National Museum of African American History and Culture

curator at the National Museum of African-American History and Culture, vocalized the museum’s mission to elevate the voices of those that have not been heard. A museum that could capitalize on attractive memorabilia from famous individuals, chooses to highlight lesser-known people. This is another instance of doing the right thing. Without a doubt, this class has pushed the integrity of my moral compass.

Throughout my upbringing, both in the classroom and at home, I have been encouraged to speak up over areas of public concern. In concurrence with my childhood instruction, Senator Tina Smith quoted Paul Wellstone, former Minnesota senator, saying “we all do better when we do better” and that civic engagement is the “glue that holds us together.” Growing up, the creation of art had always presented itself as a way in which I could express my humanitarian self. However, I could never establish a clear understanding of how the arts would truly bring about the change I was looking for. My eyes opened when speaking with Senator Smith who expressed that “in order for civic engagement to flourish, we need to have a way to come together, and art does this.” I interpreted these words as art can unite people and instigate discussions that would otherwise never occur. As a future architecture student, I understand that I have a responsibility to use this form of art as a facilitator for community gatherings. My civic engagement can be a catalyst for others’ civic engagement.

Washington Performing Arts Children of the Gospel Choir

This course has revealed the interconnective web that is art in democracy. Art exists in every sector of life and is embedded in every level of government. If there is one omnipresent theme in this class it is that the opportunity for creative engagement is virtually endless and all-inclusive. Our meeting with members of the Northfield Arts and Culture Commission illuminated that there is a niche for everyone in government. Whether you are a poet, librarian, or art teacher, there is no single prerequisite among art advocates. Indicated by the Minnesota State Arts Board and the representatives we met with, all levels of government are essential to the elevation of art in our society. As epitomized by Trisha Taylor and the Washington Performing Arts, an absence of government affiliation does not negate the difference-making potential of anyone. With all of this being said, I am optimistic and eager to explore how I can apply my artistic knowledge to my community.

Of course, there needs to be a concrete plan for change in the arts. At the federal and state level, funding for the arts must increase. In fact, Randy Cohen and Americans for the Arts, have found a correlation between students’ performance in academic subjects when they have a regular infusion of the arts. Consequently, supporting public funding for the arts simply makes good sense. Society will ultimately benefit. In our discussion with Tim Wright of Attucks Adams, a D.C. touring company, he expressed the hypocrisy of public installations meant to commemorate a historically black community but instead contributing to mass displacement of the very group of people it represents. An issue that illustrates the subject of focus in my policy proposal is gentrification. Public art must instead be a collaborative affair; it must amplify the voices of the disadvantaged and draw in the ears of the advantaged. Art should strengthen a community, not drive it away.

Take Me Out To The Go Go, a mural on the Attucks Adams tour

Arts and culture have complete relevance to our capacity to face today’s complex issues. Art inspires insights that transcend all backgrounds. Art fosters imagination and creativity, attributes that are crucial in their impact on the individual and the community. In a democratic society where a vote is misunderstood as your only important civic contribution, Professor Epstein reminds us that “the power isn’t in the vote, it is in the conversation.” This class ultimately boils down to simply (well, maybe not so simply) a conversation about the responsibility of art in democracy. After all, democracy is dependent on the arts. I thoroughly enjoyed questioning the relationship between art and democracy and am grateful for Professor Epstein, our guests, and of course, my fellow classmates for their dedication to this exploration as well.