Prior to my interim experience, I spent two straight weeks with my extended family. The fortnight was lovely, but as a result, I also spent a considerable amount of time explaining to various relatives what I would be doing during the month of January. I started following a tight script: “So I’ll be taking a class called Democracy and the Arts, and we’re going to be looking at how the federal government decides what art programs get funding and how that funding ultimately affects what art is created.” At this, my relatives would nod pensively, offer a word of support, and change the subject to avoid further obfuscation. I would breathe a sigh of relief. The truth was that I had no idea what we’d be doing! I had course descriptions and planned site visits, but I couldn’t possibly know the scope of everything we would learn and accomplish. The whole program seemed vast and confusing. Perhaps it still seems that way. Allow me to help with that feeling.

If I had to boil down my interim experience to a single cogent theme, I would talk about our emphasis on accessibility in the arts. Prior to #demartsdc, I had hardly given the idea any thought, but I’ve since realized that it’s the perfect basis for talking about democracy in the arts. Just not in the way I expected. My first such encounter came in the moments before the Kennedy Center’s presentation of three new 20-minute operas. I had forgotten to change out of my tennis shoes before the performance and I expressed my mortification to Professor Epstein, but instead of admonishing me, he lauded me for introducing democracy to the opera. I was confused, so he explained that such events are typically reserved for a very select group of individuals, namely, those who can afford nice shoes. By sporting my Asics, I was signaling that this art was for everyone and that it should be enjoyed as such. Whether or not anyone in the theater understood this message (or even noticed it) the sentiment got me thinking. We can’t have democracy in the arts if an entire class of people is excluded from engaging with the art in the first place.

A DC elementary music classroom, complete with DC Keys keyboards.

With this thought, I attacked each new site visit with a different attitude. I wanted to know which institutions were actively democratizing the arts and which ones might need some help. A particularly inspiring example was found in the work of Washington Performing Arts, an organization we were lucky enough to visit midway through the program. WPA is committed to presenting high quality performances in DC, but also to developing young artists in DC schools. With this dual mission, the organization is primed to address questions of a democratic arts society. One of its hallmark programs is DC Keys, an initiative which places twelve electric keyboards in every public elementary music classroom in the District.The intent is that all students, no matter their backgrounds, will grow up with basic piano skills. The keyboard curriculum is also designed to engage students with other aspects of music making and artistry, fostering a democratic arts community from age five and beyond. I cannot overstate how excited I was about this program. I immediately wanted to leave and start applying for grants to implement it in my own hometown. It’s amazing! By intentionally offering this opportunity to all public school students, WPA gives them a voice in the arts and shows them that anyone and everyone should participate, no matter their footwear. (This Asics metaphor is really getting some mileage.)

Briefly, something else I noted at WPA was how normal and friendly their staff were. Given the incredible work of the organization, I almost expected angelic, deified leaders who operated on a different plane of excellence. But no! They were regular people! They were obviously very passionate about their jobs, but they also really showed how far personal motivation goes in effecting change in the arts. At the end of the meeting, I felt like our group’s sense of responsibility had grown. If WPA can take an idea for equitable artistry and change the world with it, we should be able to do the same. Civic engagement and improvement, especially in the arts, only seems to take a few passionate people, and it’s been refreshing to see so many of them in DC. With those themes in mind, I wrote my final policy proposal on the excessive use of western European music in elementary music classrooms. I’m proposing a fund to help teachers pay for a more diverse curriculum that equitably addresses the cultural backgrounds of their classrooms and thereby creates more artistically engaged students. I don’t know if it’ll catch on, but I feel a responsibility to at least give the idea voice. Thanks WPA!

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Atlas_CORE_01_michael-moran-56a237283df78cf772735a09.jpg)

The Atlas Performing Arts Center, found in the H Street neighborhood.

Finally, I want to touch on the other side of arts accessibility: who goes to shows. The National Endowment for the Arts (a funder of WPA and many other organizations we visited) is prolific in its democratic support for arts-making entities. But once the art has been created, who gets to see it? Here, the democratic responsibility falls to presenters. In how they choose to display their art, they’re making a decision that could be completely democratic, or completely the opposite. We saw examples of both in DC. First, a good example. The Atlas Performing Arts Center is a shining star when it comes to accessible viewing of the arts. They have regular school matinee performances which bring in students from the local community who otherwise might not go to the theater. They constantly feature free performances by local artists in a space specifically designed for the purpose. They offer talkbacks after many stage performances in order to start discussions about improving accessibility for the immediate neighborhood. They seem committed to a genuinely democratic system of arts presentation. Everyone deserves to be a part of their space.

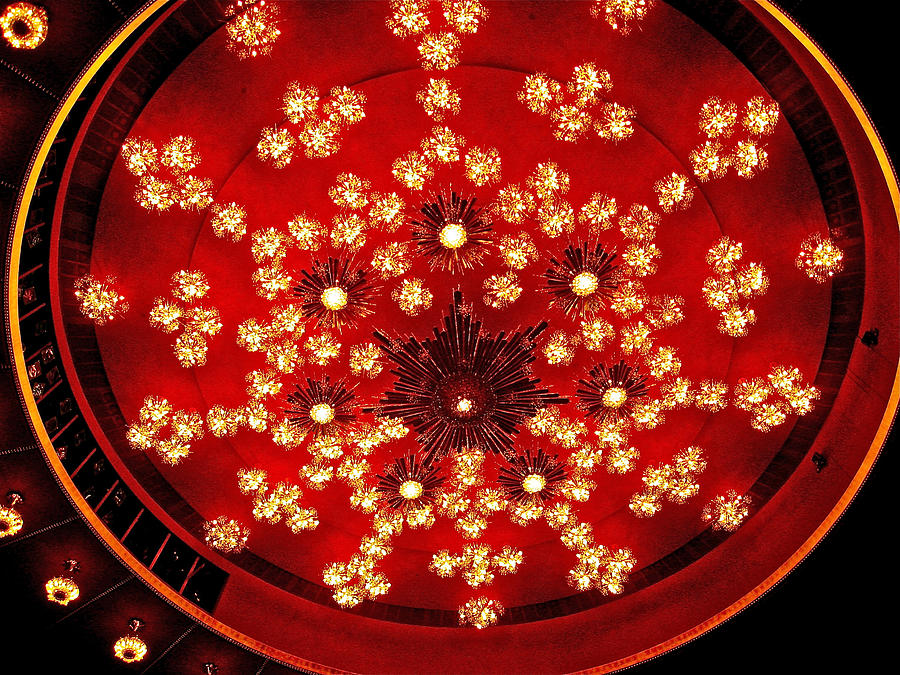

The ornate ceiling of the Kennedy Center Opera House, where we watched My Fair Lady.

On the flip side, we went to a number of performances this month that were highly inaccessible. The operas I talked about at the beginning are an example. If I walk into a venue and feel actively uncomfortable in a pair of muted tennis shoes, that event is not welcoming to all voices. I felt the same way about the Kennedy Center performance of My Fair Lady. The show was wonderful, but looking out over the audience, I couldn’t help but notice that everyone seemed rich, white, or both. (Mostly both.) And that makes sense! When a ticket to a stage musical costs more than a week’s groceries, a large part of the population simply will not come.

Of course, many people just don’t want to come. Different people prefer different forms of art, and I believe that creating art that appeals to everyone will inherently water down its quality. I’ve been using the terms “democratic” and “accessible” interchangeably throughout this post because I had wanted to suggest that everyone should be a part of artistic creation and appreciation, and I felt that both words expressed this sentiment. Here I’d like to separate the two. Works of art do not have to be democratic. They do not listen to every individual voice. Art exists on the fringe, capturing the ideas and beliefs of a select few, and it exists in the mainstream, capturing widely held maxims and ignoring those who might disagree. However, art does have to be accessible. When a group of people are arbitrarily excluded from enjoying a particular art form, that art form dies, and productions like My Fair Lady need to be wary of who is included and who is not. This is what I’ve taken away from Democracy and the Arts in Washington DC. For the sake of community, for the sake of artists, and for the sake of art itself, everyone must be given the opportunity to create and enjoy art. This is how art survives.

So I hope this has helped to clear up some of the more vast and confusing aspects of the last month. At least the whole thing is more accessible now. (Is that joke even remotely good? I can’t tell.) I’ve had an incredible time exploring, learning, and questioning in this city. I’m so grateful to everyone we met and to everyone who accommodated us. I look forward to seeing the policy work that every member of this class will no doubt effect in the future. For this and more, thank you. I will now continue to reflect, just not in a published blog.