The National Museum of African American History and Culture, or NMAAHC, is the newest Smithsonian institution. Authorized by Congress in 2003 and finished in 2016, the museum does not have a mission statement. Instead, they have four pillars that uphold their goals for the institution: explore African American history through interactive exhibitions, show Americans how their lives are shaped by global influences, explore what it means to be an American and share how those values are shown in African American culture, and to be a place of learning for a wide variety of audiences and to interact with museums that have preserved this history before NMAAHC. Dr. Reece, the curator of music and performing arts, said that NMAAHC’s goal is telling the stories of everyone in the community, not just the famous names of African American history. I found this principle to be prominent in the galleries, as they spent their energy displaying portraits and letters of everyday people.

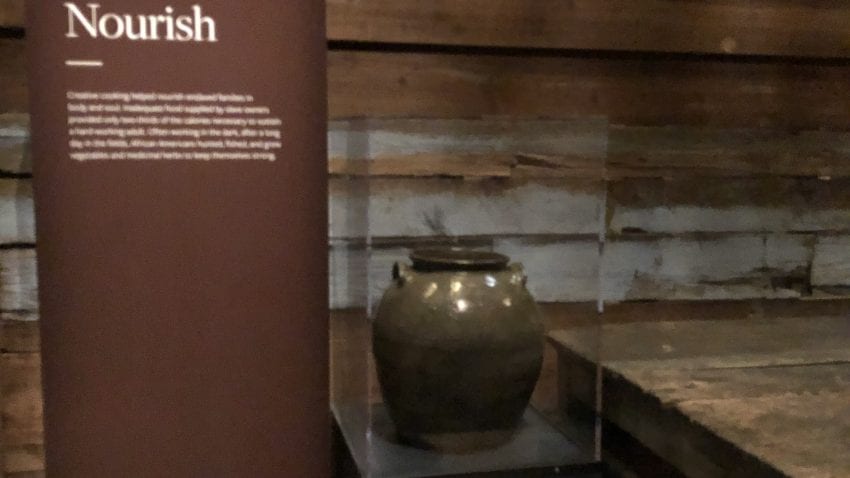

One man in particular got my attention. I was first introduced to him in my African American Art class last year. When I saw his work analyzed in an Antiques Roadshow clip, the historian called him Dave the Slave. For the better part of the twentieth century, he was identified by this moniker, not as an individual person. Dave the Slave is a minimizing identifier, reminiscent of a Gone with the Wind stereotype. Dave the Slave could be anyone. When we actually discussed him in class, we called him Dave the Potter. At the time, I figured this name was progressive. Here was this great artist being honored for his skills! He astounded historians for decades by his incredible abilities at hand-spinning such large pots. His literacy was remarkable as well, he frequently etched couplets on tops of his storage jars. Dave the Potter is surely appropriate to honor an artist, yet there is still something missing.

I didn’t quite realize what was missing until I stood in front of one of his pots at NMAAHC. There it was on the label: David Drake. You can dig through some archives and find the name David Drake in an 1870s census, the name had been there to see for almost 200 years. Standing there, I realized that all forms of “Dave the…” had a sole purpose: oppression. Historically white people have referred to African American people by their first names from a lack of respect. Historians have upheld the tradition of slavery in this country by stripping away the humanity and respect for David Drake. They had reduced him to one aspect of his life or another that they saw as his entire identity. Take that away and you are left with what NMAAHC wants you to see: a person. This person lived through enslavement and made astonishing pottery but at the end of the day, he was a person. People are complex, they are never just one thing and it would not be prudent to refer to them as such. In their mission to tell African American stories and to re-establish what had been stolen, their personhood, NMAAHC gives everyone a chance to be who they were. Dr. Reece said it best herself, that she was not trying to curate a hall of fame but a compilation of stories. The National Museum of African American History and Culture is doing fantastic work in helping a nation heal and evolve from oppression and racism, recognizing the history and celebrating greatness past and present in African American culture.