I cannot tell whether it is a testament to the artistic quality of Matthew Bourne’s Swan Lake or my own writer’s block that I am starting my blog post in this way. For all I know it is strong mixture of both, as I have written and rewritten the introduction to this about a dozen times. Each do-over had its own special reason as to why it wasn’t good enough. One was a corny bird pun, another a cliche, a joke, a summary, and so on. Ultimately, none of them felt appropriate to the nature of the performance, so I obviously chose a cop out.

I have never seen a performance like Matthew Bourne’s Swan Lake. It was something completely new to me, the dance world, and audience’s across the country, as everywhere it goes it gets rave reviews. The hype around the show was compounded by our own Alyssa Melby’s excitement to attend and listen to the audio description of the performance, and another friend of mine, Anna Cook, who is an avid fan of the ballet. Now I would be remiss not to admit I have attended only two professional ballet performances in my life prior to this past Friday, so I accept that my prior statement may lose some gravitas.

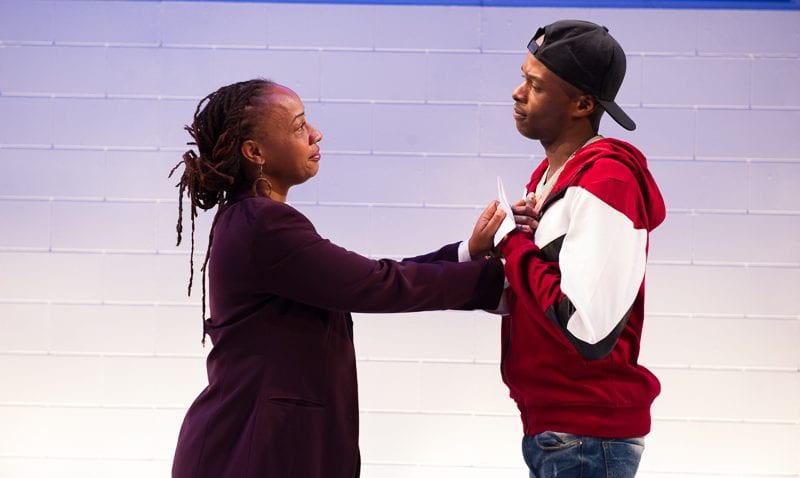

Though I may not be very well versed in the dance world, I was lucky enough to grow up in a family and community that deeply valued arts education and artistic expression. I am always interested in the arts, whether or not I have much experience with them, which is a key reason I wanted to be a part of this interim course. Production photo: Pictured Nicole Kabera as the Queen and Andrew Monaghan as her son, The Prince

Production photo: Pictured Nicole Kabera as the Queen and Andrew Monaghan as her son, The Prince

The Kennedy Center’s Opera theater was packed. My friend Anna and I were incredibly excited to see the show, and were able to get in the theater just as the performance was beginning. Due to a restaurant fiasco and shockingly long lines for the Will Call, we were unable to get to our seats before the show began, and entered as the first curtain was rising. We were escorted to a back viewing area to stand and watch the performance, garnering some disapproving looks from seated audience members. In the first act of Swan Lake, a prince is trying to convince his mother that his girlfriend is the right fit for him. The Queen takes her son and his girlfriend to the ballet, making it a very meta performance. In this modern adaptation of the story, the girlfriend was deemed unfit for the prince by the queen because of her egregious violations of performative norms. She turns the program pages too loudly, forgets to mute her cell phone, tries talking to the people next to her and even the performers in the ballet. The audience heartily laughed during each of these, partially at the action itself and partially the reaction from the uptight mother. The irony was not lost on me, standing in my puffy, cumbersome winter coat at the back of the auditorium with an obscured view, while two comfortable orchestra seats remained empty. Those who violate the norms of performances pay the price.

The performance continued, and obscured view aside, it was a struggle at moments to keep up with all of the action on stage. If you focused too long on one group of dancers, you had missed half the routine of another. While my lack of foreknowledge into the plot likely impacted that, I was left processing the massive spectacle during the intermission, at which point I called my dad and freaked out over how great the show was.

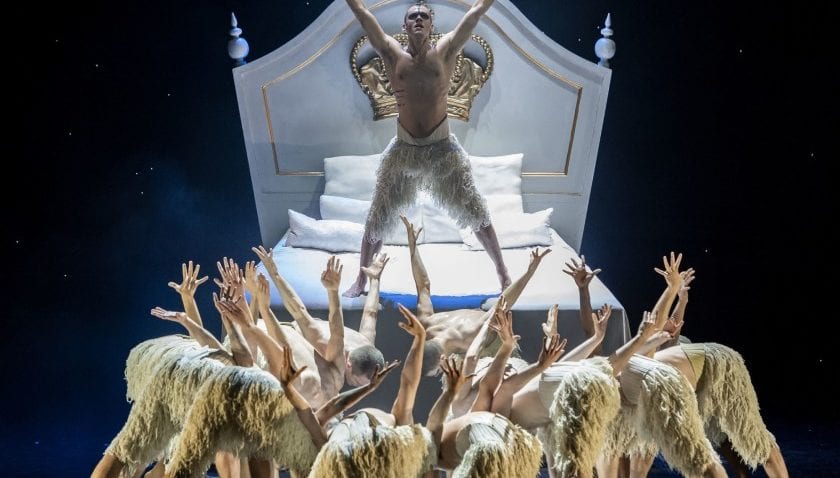

Production photo: Will Bozier as the Swan in Matthew Bourne’s “Swan Lake”

The second act delivered even more intensity than the first, and at many points I was overwhelmed. For example, when the Black Swan crashes the party, the dancing is constantly switching from solo work, to groups, to two person, and all the while the ensemble is doing their own routine. The raw physicality of everyone on stage was awe-inspiring, and during several moments during the performance I found myself literally on the edge of my seat, gripped by the movement and the story telling.

After the performance, our trio’s trip back to the hotel was filled with our reactions and thoughts to the performance. The modernization of the story, dance, and setting were lively subjects, and our conversation only ended when we left the elevator for our separate floors. When I got back to my room, I was skimming a program from a performance we saw earlier, Studio Theater’s production of Pipeline. Out of the program fell a sheet from the playwright entitled, “The Playwright’s Rules of Engagement”. It was a bulleted list of 7 rules offered by the playwright to the audience.

Rule 1: You are allowed to laugh audibly.

Production photo: Andrea Harris Smith as Nya and Justin Weaks as Omari in Pipeline.

Rule 2: You are allowed to have audible moments of reaction and response.

Rule 3: My work requires a few “uhm hmms” and “uhn uhnns” should you need to use them. Just maybe in moderation. Only when you really need to vocalize.

Rule 4: This can be church for some of us, and testifying is allowed.

Rule 5: This is also live theater and the actors need you to engage with them, not distract them or thwart their performance.

Rule 6: Please be an audience member that joins with others and allows a bit of breathing room. Exhale together. Laugh together. Say “Amen” should you need to.

Rule 7: This is a community. Let’s go.

These rules were particularly interesting because we talked a good deal in our class sessions about performance norms, and Professor Epstein has taught about them in his Musicology class. In addition to this, we saw these norms challenged first hand at a performance of another show in which the audience was filled with high school students whose reactions to the content in the performance were met with mixed reactions from our class. Their vocal responses and energy was a tense point of conversation in our class moving forward. We ultimately concluded that performative norms in all of their settings need to be challenged and reevaluated.

The above rules were so funny to me because you would never see something like this at a performance similar to the one I had just seen. The performance of Swan Lake itself mocked audience members who were too vocal, too loud, too reactive, and I started to see the line in the sand between performances like Pipeline and Matthew Bourne’s Swan Lake. As much as we would like to break down the stigma of performance norms, some art is actively curated to maintain them. If I had followed the playwright, Ms. Morisseau’s rules, during Swan Lake, I would not have caught half of the moments of the show. Some art is not suited to audience reciprocation or response, and there is something to be said that is okay. There is also something to be said in the fact that deeming some art suited or intended for audience reaction and others not only serves to further the divide between, “high” or “fine” art and everything else.

The Prince (Andrew Monaghan, kneeling) and Will Bozier as the Swan.

Justin Weaks as Omari and Bjorn DuPaty as Xavier in Pipeline.

Matthew Bourne’s Swan Lake was a performance I won’t soon forget. It challenges the dance world, it challenges audiences, and it is makes us as viewers think about how art should be taken and interacted with, and it makes us ask ourselves, “How do we communicate with art?”

Bibliography

“Review: Why Matthew Bourne’s Male ‘Swan Lake’ Is Still Radical and Relevant, 24 Years Later.” Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles Times, 6 Dec. 2019, www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/story/2019-12-06/matthew-bourne-swan-lake-ahmanson-los-angeles#null.

“Pipeline.” Studio Theatre – Play Detail, www.studiotheatre.org/plays/play-detail/2019-2020-pipeline.