As a self-proclaimed Musical Theatre nerd, it may come as no surprise that one of the activities I was most excited for was the performance of My Fair Lady at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. The Kennedy Center, a National Center for Cultural Heritage located in Washington D.C., is often thought of as an organization representing the artistic values of the American people.[1] As an artistic facility hosting a variety of art forms and ideals, a degree of artistic liberty is assumed by those involved in booking programming. However, as a federal institution funded by the American people, it is difficult to imagine how the Kennedy Center navigates program scheduling and artistic choices that may divide the public or create controversy.

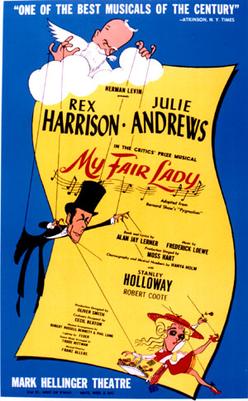

In the production of My Fair Lady, I was pleasantly surprised by firstly, the choice of musical, and secondly, some of the progressive artistic choices made by the production team. My Fair Lady, since its opening on Broadway and West-End in the 1950’s, has in many ways always dealt with themes of domestic abuse. [2] The complicated relationship between Eliza and Professor Higgins involves elements of emotional and verbal abuse, a topic which was considered taboo in popular culture until recently. Perhaps the Kennedy Center is exercising its right to free speech (a truly democratic ideal), in programming a production dealing with such dark and true themes. However, this production and a recent one done at the Lincoln Center in NYC in 2018, feature a slightly different ending than the original film. Instead of a kiss, or a malformed romance often construed by other musicals of its time, My Fair Lady ends in the fitting separation of Eliza from Professor Higgins. [3] Such an ending of a production so riddled with themes of social inequality, allows the Kennedy Center to exercise its right to free speech to address social justice issues with its tremendous platform. Even outside of the strenuous and controversial relationship between its main characters, this production also showcases the nature of class inequality between “a common, ignorant girl and a book-learned gentleman,” and although the story takes place in Edwardian London, many of the complicated themes are still relevant and visible in 21st century America. Nonetheless, the production managers of the spectacular musical have made a few choices to appeal to audiences of 2020. One vibrant example of this was the refreshing and wildly entertaining ensemble piece “Get Me to the Church on Time,” which featured dancers in drag in an exciting and comical musical sequence.

Despite being a technically out-of-date plot, I was quite pleased by the Kennedy Center’s ability to utilize the timeless aspects of the script to appeal to new audiences, and address relevant social issues. Given our experiences with other organizations funded by the federal government, I didn’t expect the degree of programming freedom demonstrated by the Kennedy Center as our National Cultural Center, but at the same time, the Kennedy Center manages not to take an overbearing political stance or as we’ve heard “shove social justice down people’s throat,” but instead presents a polished front of acknowledgement and understanding without overwhelming audiences. Perhaps this is a strategy other organizations and agencies could also use to advance their agendas while remaining politically “neutral.”

[1] “The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.” 2020. Accessed January 16, 2020. https://www.kennedy-center.org/

[2] “My Fair Lady.” 2019. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=My_Fair_Lady&oldid=933067041.

[3] Teeman, Tim. 2018. “‘My Fair Lady’ Finally Gets Its #MeToo Ending. Somewhere, George Bernard Shaw Is Applauding.” The Daily Beast, April 20, 2018, sec. arts-and-culture. https://www.thedailybeast.com/my-fair-lady-finally-gets-its-metoo-ending-somewhere-george-bernard-shaw-is-applauding.