As we walked through the repurposed 75,000 sq/ft of the underground subterranean streetcar tunnels stretching under Dupont Circle, the relationship between democratic policy and the arts seemed to seep through the colorful graffiti murals on the walls. On Jan 11, our class visited and toured the Dupont Underground, a non-profit community arts organization that serves as a multidisciplinary platform for creative expression in the arts. Originally built as a street car station in the 1940s and then designated as fallout shelter in the 1960s, the space presented itself as a unique and innovative setting to its founders Julian Hunt and Lucrecia Laudi.

Having opened in 2016, this up-and-coming renovated public infrastructure is managed by CEO Robert Meins and other administrative colleagues as well as the countless volunteers who tirelessly dedicate their time and effort to maintain the organization’s mission. Their Mission + Vision statement is as follows:

“Dupont Underground is a non-profit community arts organization run almost entirely by volunteers. Our goal is to be committed to developing a multidisciplinary platform for creative expression. We strive to reflect the diversity of our community – both artists and audiences. We endeavor to host projects and work that might not be an easy fit in more conventional venues.”

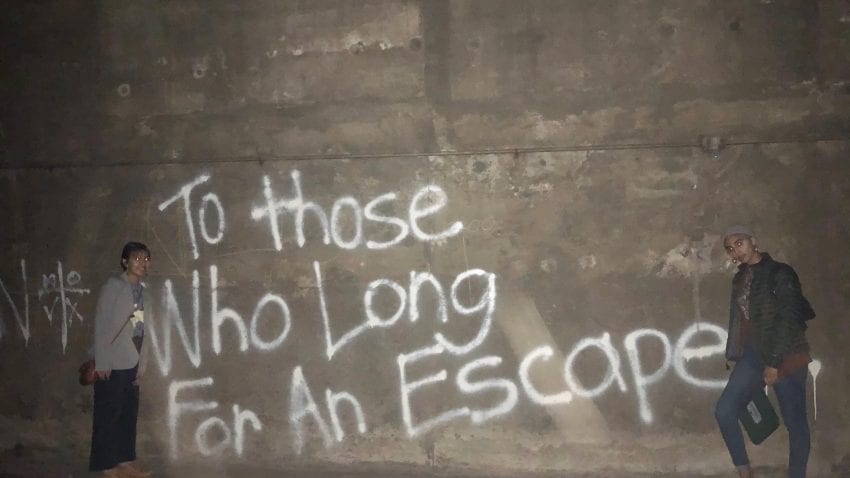

Anna Cook ’22 and Alina Villa ’20 pose next to a wall in the tunnels of Dupont Underground with a message that reflects the mission and vision statement.

The Dupont Underground is determined to create a space for those who, simply put, “long for an escape.” According to Meins, representation within the artists and musicians that reflect their audiences around the D.C. area is one of the organization’s main priorities. From queer and POC (person of color) representation in their artists and musicians to funding Go-go concerts in a very gentrified part of the city, the Dupont underground is focused on pushing past the boundaries of conventional high art and supporting artists whose artwork tests many oppressive societal norms that have been established.

Additionally, a non-profit that doesn’t procure federal funding allows for the organization to practice a different sort of artistic freedom in their cultural programming that is often not seen in institutions under the Smithsonian “trust instrumentality.” For instance, they don’t have to present as a non-partisan or apolitical organization and can support artists that have political undertones in their work and market or contextualize around those undertones.

Although this ability to have artistic freedom in curation might suggest that the organization holds a particular political stance, their display of the World Press Photo exhibition suggests otherwise. Meins, who helped to curate the exhibition and find life here in D.C., explained that the exhibition works with universities, think tanks, and embassies to not only contextualize the photos in an accurate way, but also to encourage an open dialogue about ongoing and current events to engage those who view the exhibition with the institutions who write about them.

An installation piece by a Japanese artist.

Places like the Dupont Underground are crucial for the fine arts because they allow for artists to tell their stories and have a voice and connect with audiences that reflect their diversity; to exist in a space that gives them the freedom to be who they are. While the organization has had great success in the last three years, their lease ends in April of this year and Meins explained to us that in they would need at least another 7 plus years to be able to increase funding, renovate more of the tunnels, and create a venue that is more ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990) compliant. In addition, we learned today that the Washington Performing Arts no longer hosts performances at Dupont Underground since there is no elevator or ramp for those with physical disabilities.

Overall, the experience of touring the Dupont Underground was very impactful. I could sense that it wasn’t just a trendy and aesthetic venue that caters to the hip millennials living in the area, it was a space that fosters a diverse and welcoming community that brings attention to a shared humanity through the arts. And after all, shared humanity seems to be a driving force in the power of democracy.