As the days became shorter and colder, I realized that I needed to get going on some of my research travel in Norway. Doing research on hydropower means that I have several locations to visit in different regions of Norway, and this is more difficult to do when it’s dark and rainy.

Research trip to Rjukan & the Vemork power plant

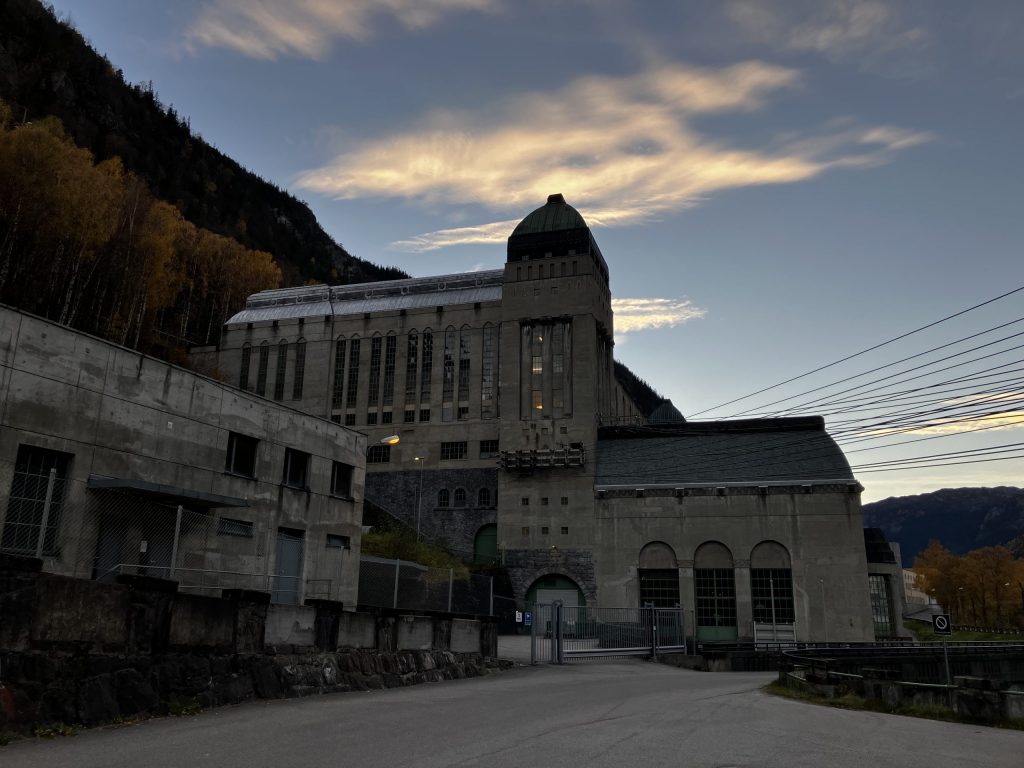

My first trip was to Rjukan to visit the Vemork power plant. Rjukan is a UNESCO world heritage site for several reasons: It was the result of a unique vision for industrial growth in the early 20th century, its workers played an important role in the organized labor movement, and under the Nazi occupation, it was the site of a famous heavy water sabotage action by Norwegian resistance fighters. The engineer Sam Eyde viewed the Rjukan falls as the potential site for a hydropower plant that could be used in the production of fertilizer by deriving nitrogen from the air. There were few people living in Rjukan in the early 1900s, so Eyde created a town for the company’s workers.

Prior to industrialization, Rjukan was a major tourist attraction, and many artists came to paint the falls. (This fame was partly based on a report by a geologist who mistakenly thought that it was the tallest waterfall in the world.) We viewed the mostly empty ravine where the falls used to be. There is now an amphitheater nearby where a theater production based on a local legend about the falls takes place every summer. The waterfall is allowed to run free during the production so that it can cause the tragic demise of a young suitor who is on the way to meet his forbidden love. (Helena Nynäs has written an interesting dissertation about the sublime aesthetics of bothwaterfalls and the architecture of early hydropower called Sublime fossefall: Et bidrag til de høye fossenes kulturhistorie i Norge.) An unanticipated challenge was that they were doing roadwork on the only tunnel that goes to the waterfall, so the road was only open for a few hours twice a day. And there was no signage announcing this at all–I somehow figured it out in my online research. Later, we ran into a Lithuanian family who had gotten stuck on one side of the tunnel because they didn’t know about the construction. This kind of travel complication is not unusual in rural Norway.

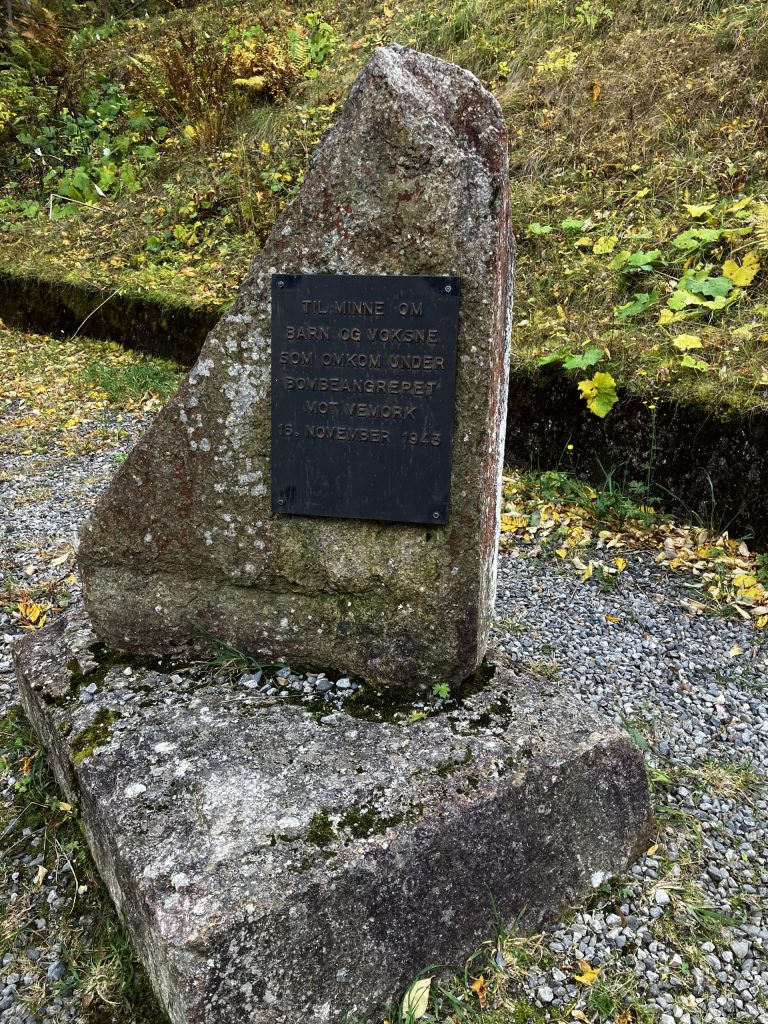

Unlike the Energy Museum in Tyssedal (which I visited in November), the museum at Vemork does not focus primarily on the history of hydropower in Norway. There are several exhibits about the development of industry and local labor movements, but the primary draw to the museum is the heavy water sabotage action. While this initially seemed less relevant to my research project on how hydropower has shaped aesthetic representations of water, I realized that I needed to consider more seriously how Nazi occupation of hydropower plants and the factories built near them would have influenced Norwegians’ understandings of hydropower. It seems likely that the association of hydropower with the production of heavy water and the development of nuclear weapons would have given this technology a more dangerous valence than it had prior to WWII. Since Annabel missed a day of school for the trip, we used the opportunity to learn more about WWII and the resistance in Norway. We had a moment of confronting difficult history when we came across information about the Norwegian civilians who were killed (despite being inside a bomb shelter) when the US and Britain bombed the village in an effort to delay heavy water production at the plant.

Since we were already in the area, we decided to hike to Gaustatoppen, a famous summit in southern Norway with fantastic views of the area. (This mountain is featured in a notable hydropower artwork I’ll write about in my December review, so it was good to be able to see it in person.) After WWII, a secret military facility was built inside the mountain for communicating with NATO, and they built a funicular inside to transport personnel to and from the site. As the military facility is no longer in use, the funicular is now a tourist attraction, so we skipped the hike down the mountain and road the funicular instead.

Literature and Film Events

Other October highlights included an event with Arundhati Roy at Litteraturhuset (a center for the promotion of literature in Oslo) in conjunction with the publication of her new memoir, Mother Mary Comes to Me, which focuses on her complicated relationship with her formidable mother. Roy has been outspoken about environmental injustice in India, particularly the damming of the Narmada River. (In Rob Nixon’s influential work Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, he devotes a chapter entitled “Unimagined Communities” to her writings on the subject. The “unimagined communities” are the rural peasants displaced by the national damming scheme, and the term is useful for thinking about other groups whose cultures and livelihoods have been sacrificed for the “greater good” in national hydropower damming schemes.) One idea that continues to resonate in my mind after reading Roy’s book and listening to her talk is the way she expresses her attitude about losing the fight against these dams: She says that, even though they “lost,” she would not have wanted to be on the winning side. I am struck by the way she maintains her focus on the values represented in the struggle, rather than the outcomes. There are several examples “lost” fights against dams in my project, and a question I am trying to answer with each example is what attitudes toward this loss are expressed in literature and film.

I also got the chance to see two documentary films about Sámi activism in a screening arranged by the Sámi House, a Sámi cultural center in downtown Oslo. The two films, In My Hand and Mer enn bare fjell (More than just mountains), depicted Sámi activist movements against the Alta dam (around 1980) and the Fosen wind farm (in 2023). The subject of In My Hand, activist Niillas Somby attended the screening and participated in a Q&A afterwards. It was incredible to be able to hear from Somby in particular, because of his key role in the Alta demonstrations, but also because we are losing many members of his generation, who were active in a pivotal period for Sámi cultural and political advancement, and it is so important to listen to their perspectives while they are still here to share them.

Other October highlights

A friend who works for the NRK archives also gave me a quick tour of NRK when I went to return a backpack she had lent me. NRK is Norwegian’s national public broadcasting company, a little like PBS and NPR. Since NRK will be moving away from their historic facility in a few years, it was exciting to get a glimpse inside.

Torgrim Sneve Nilsson Guttormsen, a former Fulbrighter to the US who I met when he gave a talk at St. Olaf about his research on the memorials at Stiklestad, was kind enough to meet me and Annabel for dinner and give us some tips on life in Oslo.

Another milestone was celebrating Halloween in Norway. This holiday seems to have gotten more popular in the last ten years: there were many excited kids talking about trick-or-treating on their way to school on the morning of the 31st. Annabel was able to trick-or-treat with a friend we met a few years ago. Her family lives in a close-knit neighborhood where the apartment buildings are designed with courtyards in the middle. This design promotes social interaction, especially between families with young kids, who are able to play on little playgrounds and ride their bikes around the courtyard. One thing we noticed about Halloween is that Norwegians seem to emphasize the scary side of the holiday more than the cute and funny sides that are also common in the US. One family created a haunted house in the basement of the building, which wasn’t too scary, but the local school we thought Annabel might eventually attend (but won’t be … more on that later) put bloody handprints in the classrooms and hallways, a move that I don’t think would go over too well in the States. (Unfortunately, this could be because violence in schools is a reality, rather than a harmless fantasy.)

I also submitted two chapter drafts–one was a final revision of an article on Nordic Nature Poetry that I’ve been co-writing with Kjerstin Moody from Gustavus Adolphus, and the other was the first draft of an article on the use of poetry by activists opposed to the Alta dam project.