Resettlement

This section specifically is dedicated to understanding U.S reaction towards Eastern Europeans and Baltics coming in and how Minnesota, specifically the town of Northfield and the Twin Cities area, served as a landing spot for many displaced persons coming over. For more information on resettlement and U.S. immigration policy, be sure to check out the International Cooperation sections.

U.S Assistance and Reaction

Baltic DP's and Communism

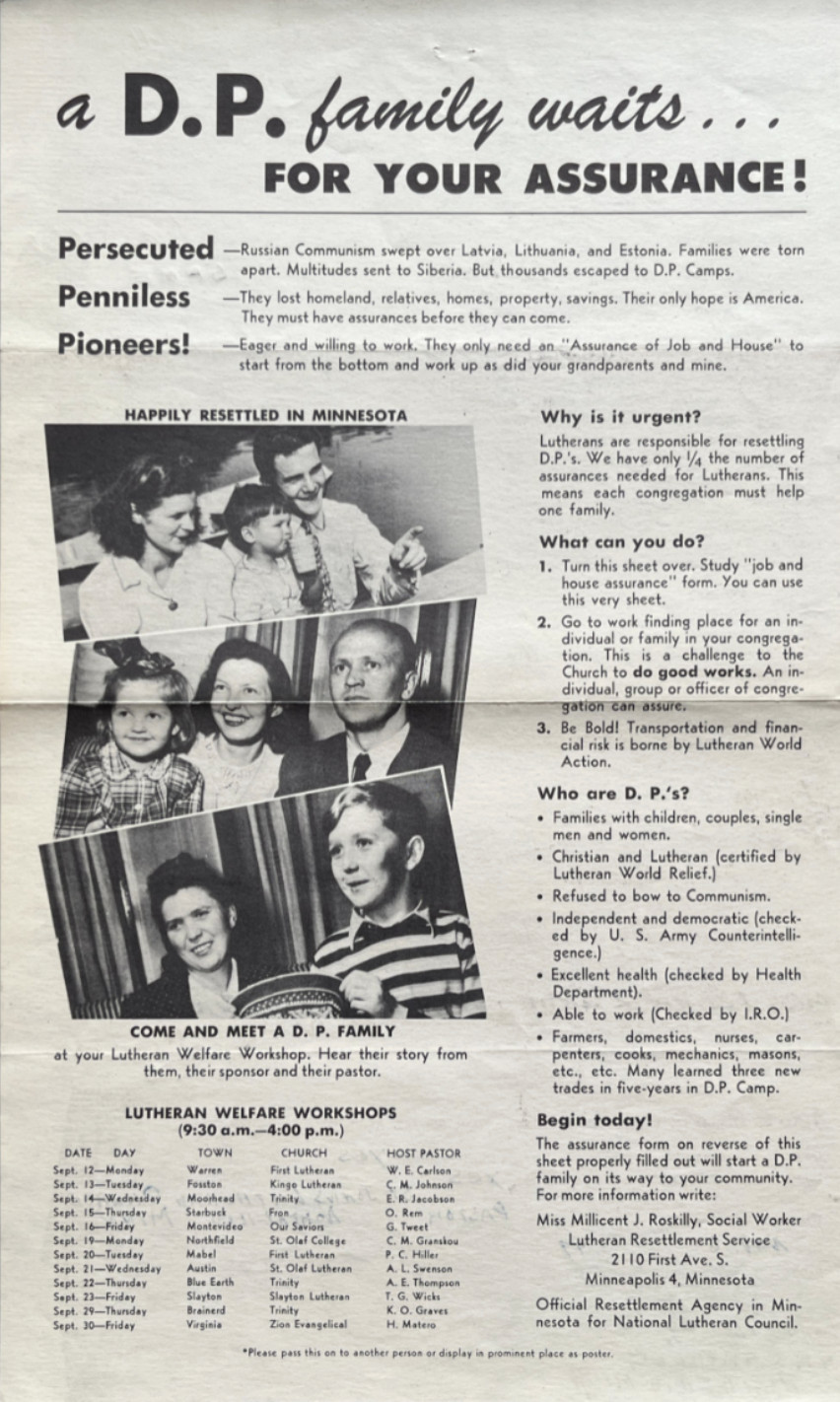

With the rise of the Cold War and anti-communist sentiments in the United States, the Lutheran World Federation (LWF) had to reconcile the Eastern European heritage and nationality of displaced Lutherans and Americans’ desire to not bring in communists. An example of how Lutheran agencies coped with this was through the document to the right by the Lutheran Resettlement Service of Minnesota. Here they reassure their American audience that displaced persons are, in fact, not communists but rather “the trained free thinking people who refuse to go back to their Soviet dominated countries.”1 They also reassure their audience that displaced persons were screened multiple times to see where their loyalties may lie.2

Anti-communist sentiment was also present among displaced members of the “Churches in Exile” and displaced staff of LWF-SR. Edmund Smits, program director of the Lutheran Study Center at Imbshausen and Latvian displaced person, for instance, describes communist rule as having “very noble human aims from the outside, but on the inside, the most inhuman killing of people who were nothing but right good fellows.”3 Given displaced persons history with Soviet occupation, clearly neither side had pro-communist sentiments, but American audiences still needed to be reminded of people like Smits in order to want to provide aid.

Sponsors

The relationship between a sponsor (someone providing a job to someone immigrating to the U.S.) and a displaced person had a delicate balance. Work life and acculturation proved to be difficult for both sides; displaced persons felt a distinctive homesickness and untrusting view of this new country, while American sponsors expected an overwhelming gratefulness to their job offers and housing provisions.4

Many immigrants came over to the U.S. to work on farms, but often did not plan to stay there given their experiences with farm work under Soviet occupation. Naturally, instead, they moved from their original sponsored homes and jobs over to cities, leaving American farmers disappointed with the loss of workers. Yet, sponsors also at times did not treat those they sponsored well, with hundreds of Latvians exploited through Mississippi sharecropping situations, in Louisiana sugar cane fields, and in California citrus groves.5

The Lutheran Resettlement Service (LRS), understanding the traumas and accompanying distrust refugees had, and attempting to provide space for these emotions, reached out through letters to newly settled displaced persons to ask whether living conditions were satisfactory. Yet, showing their hope for acculturation, they also suggested that they join local Lutheran congregations, where they might learn English and worship, but this was a suggestion that was not always welcomed.5 In the end, autonomy, community, and expectations for quick acculturation all clashed within this sponsor-sponsored dynamic.6

Postwar to Cold War

With fears of communism at a rise with the beginning of the Cold War, ethnic German and Baltic refugees tended to receive more support from American authorities when they deployed more ‘anti-communist patriotic propaganda.’ The DPs came to the U.S. with strong nationalistic feelings for their home countries and desires for liberation from Soviet rule. Yet, with this passion for liberating the Baltics, the DP’s were faced with American churches who did not share their sense of urgency in fighting for freedom.

Here the LSR and LWF faced the conundrum of the Church’s role in politics. The general stance of the LWF was that it was God’s will to deploy the Baltic DPs from their nations, and that it could have just as easily been Americans. Therefore, it was God’s will to serve their fellow Lutherans. LWF also emphasized that Americans should not expect assimilation from the Baltic DPs who were grieving the loss of their homeland.7

Minnesota

Refugees Turned St Olaf Students

.Six Lutheran displaced persons immigrated from the Baltics to attend school at St. Olaf College. Yet it is important to note that it is unclear whether LWF and LRS aided in their immigration.8 Below shows a snapshot into four of these displaced students’ lives:

Ruta/Rute Jaunzems was born in Riga, Latvia, where she later studied medicine at the University of Latvia and piano at the Conservatory of Stuttgart. She immigrated to Minnesota without her family since both her parents were deceased. She graduated from St. Olaf College in 1950 with a B. A in piano and was a member of the German and music clubs. Ruta/Rute Jaunzems passed away just three years later in 1953.7

Airis Abolins was born in Riga, Latvia and attended the Latvian high school in Eislingen, Germany. He was confirmed by Archbishop Grünbergs, the Archbishop of the Latvian Lutheran Church in Exile and a member of the LWF executive committee.8 Airis studied mathematics at the University of Stuttgart. His parents remained in a displaced persons camp in Germany when he immigrated to Northfield, Minnesota. He was a member of the French, German, economics, and boilermakers club and graduated in 1951 with a B.A. in economics and mathematics. Airis Abolins passed away years later in 1988.9

Aina Ozolins Nucho was born in Riga, Latvia and later lived in Czechoslovakia. She studied theology at Tubingen University in Germany. She arrived in Northfield in September 1949 with the goal of becoming a curate in the Latvian Lutheran Church. She was a member of the German club and graduated with a B. A. in religion in 1950. She also received her Master of Social work from Bryn Mawr College in 1957 as well as her PhD in 1966. She passed away in 2011.10

Ulo Lepik was born in Viljandi, Estonia. He later immigrated to Northfield in 1949, where his fiance, sponsored by LWF, already worked at Carleton College. He married his wife at St. John’s Lutheran Church. He spoke German, Russian, English, and Estonian and studied to be a doctor, but he did not finish his degree at St. Olaf College.11

The Latvian Lutheran Church

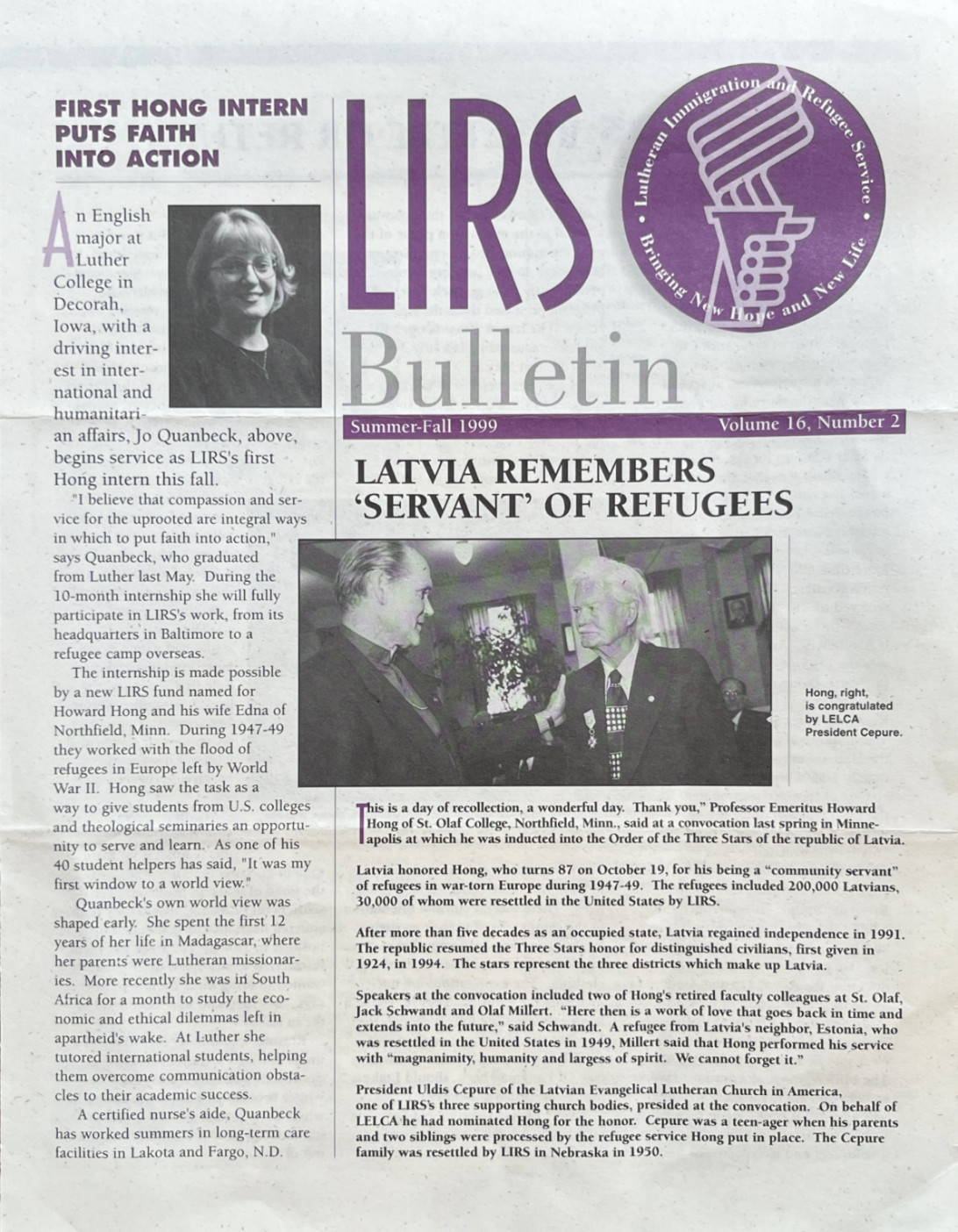

The Latvian Lutheran Church maintained many connections with Lutheran World Federation and American Lutheran services. For one, Latvian Archbishop Grünbergs participated in the executive committee for the Lutheran World Federation.12 Lutheran World Action, an American Lutheran fundraising organization, also served to aid in the resettlement of thousands of Latvians.13 Lutheran World Federation Service to Refugees directors, such as Dr. Howard Hong, even took part in these connections. Hong helped establish regular radio broadcasts of Latvian church services over the local station WCAL. With the approval of the Latvian archbishop, Dr. Hong selected Peteris Langins, then hospital chaplain in Germany, to start organizing Latvian Lutherans in Minneapolis. Hong’s impact was recognized when he was awarded the Order of the Three Stars on the highest level by the Latvian government in 1998 for his work on behalf of refugees from Latvia (see photo to the left).14

In the smaller sense, some Baltic congregations in the United States had direct connections to the Lutheran World Federation through sponsored members. For instance, in the Minneapolis and St. Paul Latvian Ev. Luth. Church, some members like Biruta Sprud’s family who immigrated in 1957 and many of their acquaintances came with the aid of the Lutheran World Federation who paid for their transportation. These fees had to be repaid in a specified time slot, creating urgency for family members to find jobs and contribute back.15 Their contributions did not stop there; for many years the Minneapolis and St. Paul Latvian Ev. Luth. Church solicited contributions from their members for Lutheran World Action and the Lutheran Welfare Society, American organizations which aided refugees alongside Lutheran World Federation.16

However, it is important to note the independence that Baltic congregations also desired. Once Baltic Lutherans came to the U.S, they created congregations often separate from American churches in order to preserve religious and cultural nuance. For instance, English was not adapted into Baltic Lutheran Churches in America until two or three generations later, to accommodate new generations whose first language was English.17

Special thanks to Biruta Spruds and Anna Hobbs from the Latvian Evangelical Lutheran Church or Minneapolis- St.Paul Libraries for their research on how the LWF connects to their church and for their interest in our project.

St. John's Lutheran Church

Exceptional aid was provided to displaced persons by St. John’s Lutheran Church in Northfield, Minnesota. For instance, in Edna Hong’s Book Of the Century, she gives noteworthy recognition to the women of St. John’s. She describes how they handled the necessity of providing DP families with clean and furnished homes, and supplied with food, clothes, soap, quilts, and every other amenity needed for a comfortable life.

With the aid of St. John’s and the work of many Northfield residents, 250 DPs immigrated to Northfield. However, this brought some fear of an overwhelmed job market in Northfield as well as some local pushback on the DP Act which allowed more DPs into the U.S.. Ultimately, almost all of the 250 DPs resettled in different cities throughout the U.S. after their assurances were fulfilled in Northfield.18

Endnotes

- Lutheran World Service, St John’s Lutheran Church Archive, Northfield, MN, Box 3.

- Ibid.

- Edmund Smits, Autobiography of Edmund Smits, Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA) Region 3 Archives, Luther Seminary St. Paul, MN.

- To Friends and Relatives of Ethnic German Refugees, The Lutheran Resettlement Service, ELCA Chicago Archives Box 2.

- L DeAne Lagerquist, “Fellow Workers: Lutherans’ Service to Refugees as Public Engagement,” Journal of the Lutheran Historical Conference 1 (2011): 205–20.

- To Friends and Relatives of Ethnic German Refugees, The Lutheran Resettlement Service, ELCA Chicago Archives Box 2.

- Ibid

- Edna H. Hong, The Book of a Century: The Centennial History of St. John’s Lutheran Church, Northfield, Minnesota, Kierkegaard Library: Related Thinkers (Northfield, Minn: St. John’s Lutheran Church, 1969), 108.

- Lutheran World Service, St John’s Lutheran Church Archive, Northfield, MN, Box 3

- Richard W. Solberg, As between Brothers: The Story of Lutheran Response to World Need (Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1957).

- St Olaf Registrar.

- Minneapolis and St. Paul Latvian Evangelical Lutheran Congregation’s List of Church Services and Notices, October 1951, p.2.

- Minneapolis and St. Paul Latvian Evangelical Lutheran Congregation’s List of Church Services and Notices, August, 1951.

- Minneapolis and St. Paul Latvian Evangelical Lutheran Congregation’s,Svētrīta Zvani, Nov. 1951, p. 7.

- Minneapolis and St. Paul Latvian Evangelical Lutheran Congregation’s List of Church Services and Notices, October 1951, p.2.

- Minneapolis and St. Paul Latvian Evangelical Lutheran Congregation’s,Svētrīta Zvani, Nov. 1951, p. 7.

- Mark Granquist, interview with Anneke Shiller and Natalie Wilson, recorded by Xiaoyang Hu and Amanda Randall, June 6th, 2023, Tomson Hall, St. Olaf College.

- Edna H. Hong, The Book of a Century: The Centennial History of St. John’s Lutheran Church, Northfield, Minnesota, Kierkegaard Library: Related Thinkers (Northfield, Minn: St. John’s Lutheran Church, 1969).

Click the button below to view the complete bibliography for this digital exhibition.

Photo Credits (from top to bottom, left to right)*

- IRO camp, Lutheran World Federation Service to Refugees 1947-1949 Album, used with permission of the Lutheran World Federation and Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.

- Flier calling Lutheran families to Sponsor Dp families, Lutheran World Service, St John’s Lutheran Church Archive, Northfield, MN, Box 3

- Ulo Lepik, Ruta Jaunzems, and Aris Albolins pictured in the St Olaf Messenger, Gordon Morse. “Campus Goes Cosmopolitan; Oles Arrive” The Manitou Messenger (1916-2020). 1949. https://stolaf.eastview.com/browse/doc/45920026.

- Professor Howard Hong receives the Order of Three Stars of the Republic of Latvia, the highest honor a non-Latvian may receive. (St Olaf Rare Books Room )Latvia Remembers ‘Servant’ Of Refugees, From St Olaf Rare Books Room.

*Description ordering is based on computer view. If viewing this page on a smartphone or tablet, please check the descriptions provided as the ordering may be distorted.