Refugee Services

by Anneke ShillerWhen appointed to be first president of the Lutheran World Federation in 1947, Anders Nygren admitted to the convention, “the work is great and we are small.”1 For the Lutheran World Federation Service to Refugees, the scene on the ground that first year was overwhelming. The so-called DP Camps were overcrowded, and the people were restless, hungry, sick, and weary. But, as documented in this section, LWF-SR staff aimed to match their support to the spiritual, personal, and physical needs at hand.

Aim

“We can never be a Moses but rather an Aaron helping Moses hold up his arm.”2

To understand the aim of the Lutheran World Federation Service to Refugees (LWF-SR), one must first understand the situation of displaced pastors and the “Churches in Exile” that gathered in the DP camps where the LWF-SR staff offered their service.

Like Aaron did for Moses in the Book of Exodus (Exodus 17:12), LWF-SR structured its work around the Churches in Exile and displaced pastors to lift them up to thrive self-sufficiently. The LWF-SR accomplished this by recruiting displaced pastors for their team, including Bruno Ederma (congregational care), Edmunds Šmits (Imbshausen Lutheran Study Center program director), and Janis Rozentals (chaplaincy service), to direct support. The LWF-SR also obtained other crucial supplies for pastors servicing their churches, such as communion packets and printing services to publish Bibles, catechisms, and hymnals in the communities’ languages. In this way, the LWF-SR acted as Aaron, the support, but not the main figure of this chapter of the history of the Churches in Exile.

“The church must go to the church.”

“The Aim–Ministry of the Lutheran Churches on Behalf of Lutheran Churches-in-Exile and their People”3

However, this motif of an Aaron-Moses relationship is a later addition in a larger imagined aim and history of LWF-SR work.

Even before the official constitution of the Lutheran World Federation, LWF-SR work had already unofficially begun through the dedicated work of Dr. Michelfelder, Dr. Bodensieck, Dr. Clifford Nelson, and Rev. Carl Schaffnit. These forerunners set the groundwork for Howard Hong and his two student volunteers, Kenneth Senft and James V. Anderson, who set the work of LWF-SR to work on the ground starting in summer of 1947.

Starting off running, these people embodied the concept of “the church must go to the church,”3 an idea emphasized at the Lund convention where the Lutheran World Federation was created. As their work progressed, they began to focus more on being “of assistance to the refugee pastors in carrying out their ministry,”4 not necessarily being the only aid to camp congregations. It simply took the work and flexibility of these forerunners and teams to find the core purpose of their work: of being an Aaron.

Needs

Need begins, first, with the person in need. Lutherans living in displaced persons camps in occupied Germany and Austria included three main groups of people receiving LWF-SR aid: pastors, “special hardship cases,” and the everyday person. Each group involved a particular situation with specific aid, but regardless of specifics, all were in dire need of spiritual and material support during this time.5

Pastors’ Needs

After suffering religious persecution under Soviet Union control, pastors were in need of a break they did not receive. More often than not, pastors were left without or with little pay for their work in IRO/displaced persons camps, leaving them with less food and supplies. Their underpaid work also included servicing and traveling to multiple congregations due to limited religious leadership. For instance, Pastor Alexander Abel traveled by rail 12,515 kilometers in one year to minister to various Estonian congregations.6 Additionally, these pastors were often left with inadequate space and religious literature to even hold a service. With travel costs high, an unequal pastor to congregation ratio, sparse religious materials, and little food, pastors were struggling to make ends meet.

“Even our pastors are broken and dismayed men.”

Edmunds Šmits, Imbshausen program director7

“Special Hardship Cases”

As defined by an U.S. area director, Reuben Baetz, “special hardship” cases include those that are “sickly babies, widows with children, and–later on–the chronically sick or ex-TB cases” as well as those disabled from World War II and elderly refugees.8 In post World War II Germany, tuberculosis and rickets were rampant among camp populations due to deficiency in diet. Many men had lost limbs to the war and many women, left now as single mothers, lost husbands. Also, while the 1948 Currency and Economic Reform benefited those that could work, many considered “special hardship” cases were left worse off. In the end, extra food and medicine were a dire need for “special hardship” cases.

The Everyday Person

The position refugees found themselves in by 1947 was one Edna and Howard Hong described as “a marriage to idleness” with “suddenly having no purpose but to keep from the grave.”9 Refugees were stuck in a position of both being stateless in a strange place and having little sense of purpose. In camps, food was redundant and insufficient. Jobs were not always available, especially those in the fields they were in before. Cultural and religious events were organized but with limited resources. Money had no real use and the black market was pervasive. Families were stuck in cramped living quarters with communal bathrooms and kitchens. Lastly, resettlement was both a desire but also a concept that felt very unachievable. Clinging to one’s faith and hope proved to be a struggle for every refugee amidst this chaotic world quite unlike home.

“An atmosphere of constant anxiety of new hopes changing with hopelessness.”

H. Pullerits, on what an IRO resettlement center is like10

Support

As shown above, needs are complex, ever-changing, and specific. As a result, LWF-SR had to organize itself according to the needs at hand. To do this, they centralized on two main types of needs: spiritual and material. With an understanding of the many physical needs at hand (additional food, medicine, and clothing) and a desire to spiritually uplift their brothers and sisters, LWF-SR created around five main programs (congregational care, the chaplaincy service, study centers, religious education, and resettlement) with three companion programs (youth work, publications, and student work). These programs allowed for religious life in camps to be more consistent and attended to, for pastors to get those additional supplies they need, and for people to be nourished appropriately.

But this is not to say the programs were perfectly organized or ran smoothly each time. The resettlement program alone faced plenty of challenges with immigration laws, problems with documentation, and issues with travel costs. Also, suffice it to say, the program started off running but not organizing. Overlap between programs and people filling multiple roles were often occurrences, and policy complications needed to be solved. Nonetheless, led by an impressive staff, these programs still found a way to support the Churches in Exile the best they could.

Endnotes

- Lutheran World Federation Assembly, “Minutes of the Convention,” in The Proceedings of the Lutheran World Federation Assembly Lund, Sweden, June 30 – July 6, 1947 (Philadelphia: United Lutheran Publication House, 1948), 24.

- Lutheran World Federation, “The Aim–Ministry of the Lutheran Churches on Behalf of Lutheran Churches-in-Exile and their People,” in Lutheran World Federation Service to Refugees in Germany 1947-1949. Materials for Report, vol. 1, ed. Howard Hong (1949), 194.

- Ibid, 194.

- Reuben C. Baetz, “Ministering to the Displaced Persons in Germany” in Service to Refugees, 1947-1952, (Geneva: Lutheran World Federation, 1952), 11.

- Sources that contributed to the background for the need’s section: Reuben C. Baetz, “Ministering to the Displaced Persons in Germany” in Service to Refugees, 1947-1952, (Geneva: Lutheran World Federation, 1952); Betsy Barton, The Problem of 12 Million German Refugees in Today’s Germany (Philadelphia: American Friends Service Committee, 1949); Edna Hong and Howard Hong, “I am a Stranger Here,” 1947, Box 3, Folder 4, National Lutheran Council Division of Public Relations Correspondence Files Correspondence Files, 1947-1949, Archives of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, Chicago, United States; Lutheran World Federation Service to Refugees in Germany 1947-1949. Materials for Report, vol. 1, ed. Howard Hong (1949); Material Relief Germany Supplies, 1951 1949, Box 9, Folder 1, Lutheran World Federation Archive, Geneva; David Nasaw, The Last Million: Europe’s Displaced Persons from World War to Cold War, (New York: Penguin Press, 2020); Mark Wyman, DP: Europe’s Displaced Persons, 1945-1951 (Associated University Presses, Inc., 1989).

- A. Hinno, “Report of the Work of the Estonian Ev. Church in the U.S. and French Zones of Germany,” in Lutheran World Federation Service, 68.

- Edmunds Šmits, “The Idea of Lutheran Study Center,” 1949, S 09 rep Nr. 394, Landeskirchliches Archiv, Hannover, Germany.

- Baetz, “Ministering” in Service to Refugees, 14.

- Edna Hong and Howard Hong, “I am a Stranger Here,” 1947, Box 3, Folder 4, National Lutheran Council Division of Public Relations Correspondence Files Correspondence Files, 1947-1949, Archives of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, Chicago, United States.

- H. Pullerits, “My Story for a Comprehensive Report,” in Lutheran World Federation Service, 371.

Click the button below to view the complete bibliography for this digital exhibition.

Photo Credits (from top to bottom, left to right)*

- (Heading) Young girl with her family and an LWF officer looking at a woman writing on a typewriter, Lutheran World Federation Service to Refugees 1947-1949 Photographic Section, used with permission of the Lutheran World Federation and Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.

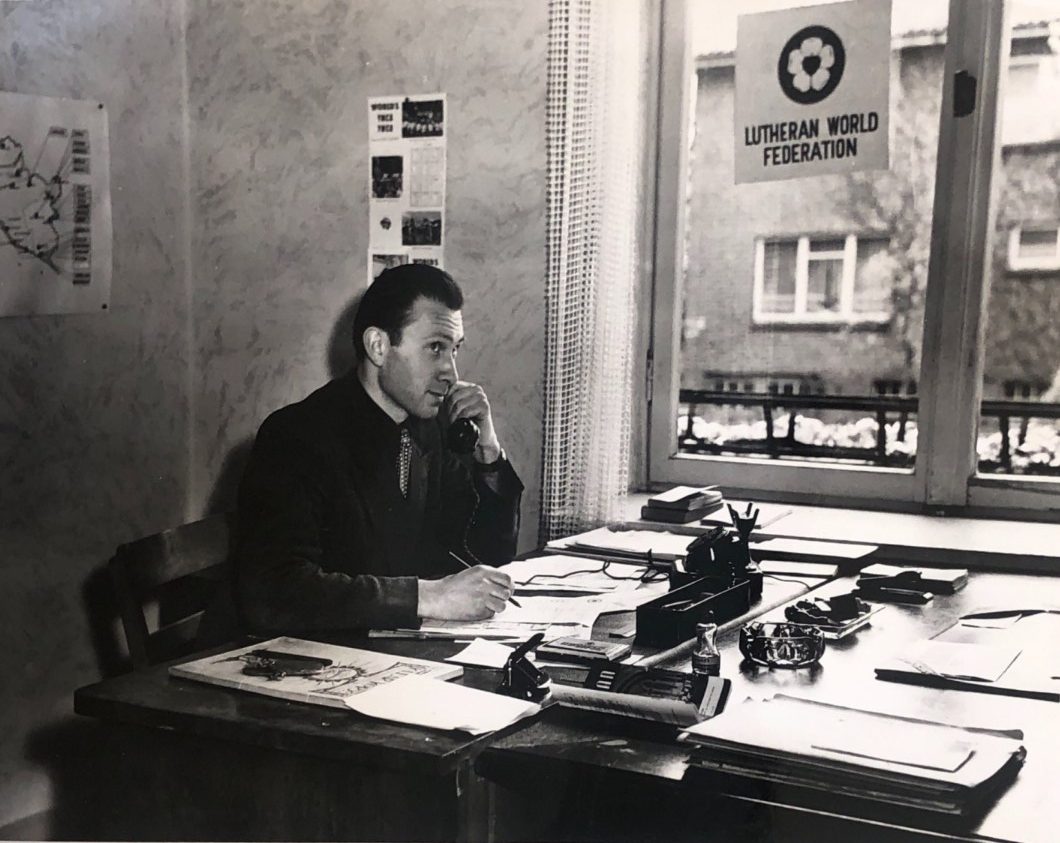

- Man on phone in office with Lutheran World Federation flier on window, Lutheran World Federation Photographic Section, used with permission of the Lutheran World Federation and Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.

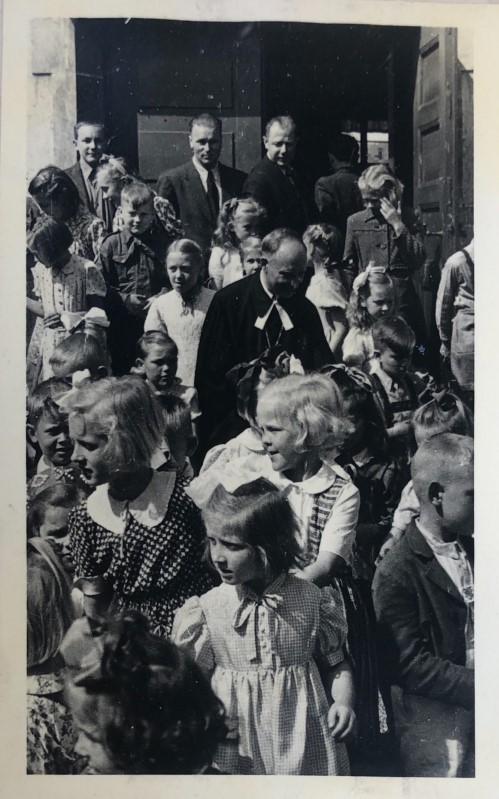

- Pastor in black robes surrounded by children, Lutheran World Federation Photographic Section, used with permission of the Lutheran World Federation and Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.

- Older woman with two children sitting next to a table full of supplies, Lutheran World Photographic Section, used with permission of the Lutheran World Federation and Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.

- Two pastors holding bikes, Lutheran World Federation Photographic Section, used with permission of the Lutheran World Federation and Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.

- Six men working at a table full of tools and jewelry, Lutheran World Federation Photographic Section, used with permission of the Lutheran World Federation and Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.

- One family of three sitting on a bed (left) and a mother feeding her child (right), Lutheran World Federation Photographic Section, used with permission of the Lutheran World Federation and Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.

- “Lutheran World Service” badge, found in box 394, Landeskirchliches Archiv, used with permission of the Lutheran World Federation.

- Six people in a hospital room with one in bed, Lutheran World Federation Photographic Section, used with permission of the Lutheran World Federation and Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.

*Description ordering is based on computer view. If viewing this page on a smartphone or tablet, please check the descriptions provided as the ordering may be distorted.