Soviet and German Occupations of Baltic States

Baltic Lutherans had varied experiences with occupation and war. This page begins to summarize the experiences they may have had that drove them to flee and impacted their worldview. Two main occupations are important to discuss in this history of the Baltic states during WWI and WWII: the Soviet and the German occupations.

The total number of those deported, murdered, or missing during the Year of Terror (1940-41) under Soviet occupation is 34,250 Latvians, 39,000 Lithuanians, and 61,000 Estonians.2

Soviet Occupation

Estonia

The first Soviet occupation of Estonia occurred between 1940 and 1941. Following the Bolshevik motto “religion is the opium of the people,” the Soviet Union banned religion in public areas (schools, broadcasting, and periodicals) as well as private settings (singing sacred music, devotional literature, and theological studies). At the same time, anti-religious propaganda was implemented throughout the country’s schools and radio stations. Finally, taxes that paid the congregation were banned with clergy members being categorized as non-workers and capitalists.

During both occupations, the NKVD-Soviet secret police were notoriously known for interrogating and arresting clergy members at night. They threatened them and their families for information and encouraged criminalizing fellow members of the congregation. In one year alone, two Evangelical Lutheran pastors were murdered, seventeen were arrested and deported to the Soviet Union, six were drafted into the Red Army, twenty-seven members of the parish were murdered, and a number of leading church members were arrested and deported to Siberia.

In the second Soviet occupation (1944 to 1948), these conditions only worsened. More and more pastors were deported to concentration camps in the Soviet Union, while those that remained were not able to observe church holidays or obtain suitable rations.1

Latvia

aaLatvia first became under Soviet power in January 1919. At this time, the Soviets began their reign of terror through arrests, kidnapping, torture, and shootings, killing a total of 6,000 people in Riga, Latvia. By May 1919, the combined Latvian and German forces drove out the Soviets for a short time, promoting Latvia’s positive attitude towards Germany.

During the second occupation in 1941, during the “Year of Terror,” theology schools were banned, religious leaders were hunted down, arrested, or disappeared, and anti-religious propaganda was extreme.

But it was not just the religious leaders experiencing this terror. More generally, Latvians remember the deportations, arrests, and killings of June 1941 as a genocide aimed at wiping out the Latvian nation, while the Soviets claimed to be relocating Latvians to prevent a bourgeois uprising. This technically was not Latvian genocide, as the NKVD was targeting specific political and social groups that often contained non-ethnic Latvians, like Jews.2

Lithuania

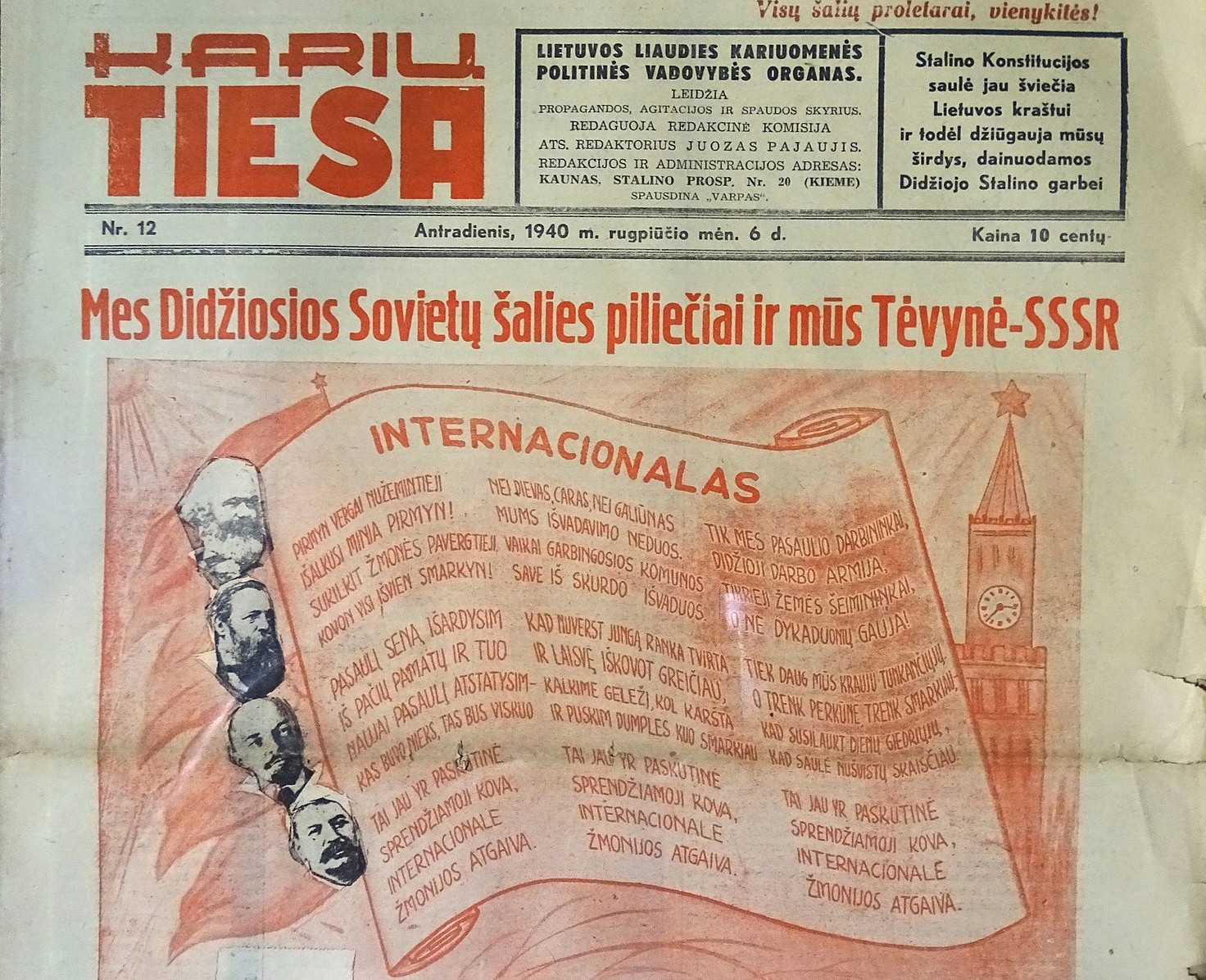

During the Soviet occupation and annexation of 1940, the Soviets took advantage of Hitler’s invasion of France by once again invading the Baltic states. In May of 1940, the Lithuanian people and government were accused of kidnapping Soviet soldiers and plotting an anti-Soviet conspiracy in the Baltic states.3

More research into Lithuanian occupation will come with future iterations of research. For now, here are some resources into understanding Lithuanian experience with occupations:

German Occupation

German Invasion

The 1941 German occupation of the Baltic states is sometimes referred to as a “liberation.” For some Baltics, this feeling rang true, and this sentiment is reflected in scholarship on that history. When German forces entered Latvia, they were greeted by cheering crowds of Latvians (see photo, right). Relief was felt for many, as they felt they were being “liberated” from a year of totalitarian Soviet rule.4 Yet liberation did not mean freedom for all. The Germans used the brutality and intensity of Soviet rule over the Baltic states (1940) to their advantage; to receive the Germans as liberators from the Soviets laid the groundwork for the kinds of collaboration that existed between Germany and those under its occupation of the Baltics. 5 The Baltics were eventually incorporated under a German civilian administration called Reich Commissariat Ostland. Under this administration, many Baltic citizens joined Waffen SS or auxiliary police units. Reasons for joining varied, but many’s participation was undergirded by a sense of patriotism, hope for an independent state, and anit-communist sentiment. 6 Meanwhile, the Jewish peoples of the Baltics became subject to the same persecution and policies of extermination carried out by Germany in Eastern Europe. In Latvia alone, which had the second largest Jewish population of the three Baltic nations, historians estimate that by the end of 1941, the Germans, with varying levels of assistance from other Latvians, murdered at least 69,750 of the country’s estimated population of 80,000 Jewish people.7

As the war returned in 1944, Latvian refugees began gathering in Riga, Latvia but feared the return and spread of maltreatment under Soviet occupation. The Germans, despite considering providing aid, did nothing to provide much needed food and shelter. In the end, while tens of thousands of Latvian soldiers, some inside SS units, stayed to fight for Latvia’s independence, hundreds of thousands of refugees chose to flee west. Seeking shelter from the war and bringing what they could, they traveled down roads crowded by military convoys.4

SS Entanglements

The Waffen SS describes the Estonian, Latvian, and Ukrainian auxiliary units commanded by Nazi Germany. Baltic connection to these units and Nazi German sentiments is tenuous. Modern evidence suggests there was a positive movement of Estonians and Latvians to enlist as local police, concentration camp guards, and anti-partisan troops. The Balts were likely motivated to enlist as retaliation against Soviet oppression or for their assumptions that Jewish people supported the Soviets and communism. These began as volunteer units, but as the need for men grew, the Nazis began conscription. In the end, Waffen SS units killed thousands of Jewish people and participated in the suppression of Jewish ghetto uprisings. The murder of millions of Jews would not have been possible without the assistance of these auxiliary units.5

However, after World War II, the international tribunal of Nuremberg determined that Balts were forcibly drafted in obvious disregard of international laws, and it was therefore unjust to classify former members of Latvian Legion as collaborators of Nazis and bar their immigration into the US. As a result, the U.S. State Department deemed many Baltic persons as eligible for immigration, despite their SS entanglements.6 Another lasting consequence of this was that only known war criminals were subject to fair scrutiny.

While Lutherans at the time wanted to save the Balts from Soviet oppression and like much of the US post-WWII, prioritized anti-communist sentiments over anti-Nazi ones, this was not a perfect system of scrutiny and soon this created tensions with Jewish organizations and modern understandings.7

Volksdeutsche/Ethnic Germans

Volksdeutsche or Ethnic Germans included those with German heritage yet were residing outside of Germany such as in Poland and Eastern European countries (ie. Baltics, Romania, and Ukraine).

However, this definition is not so simple when looking at the history of WWII. As Doris L. Bergen contends, Volksdeutsche was a term created with the purpose of motivating Nazi movement into Eastern Europe, creating a rise of anti-Semetism and Nazism in ethnic Germans, and expanding ranks of SS units. For instance, Nazis often made ethnic Germans beneficiaries of land taken from Jewish people. Yet they also made ethnic German-ness a loose definition which often relied on a display of Nazi sentiments.8 Through intermarrying, speaking different languages, or merely not following Nazi sentiments, not all ethnic Germans followed this definition of “German-ness,” which made them vulnerable to being sent to concentration camps or having their children taken and sent to a “more German” family.9

Even before the fall of WWII, around May of 1945, expulsions of ethnic Germans from their countries to Germany and Austria began. Yet, this was not the beginning of ethnic German flight with around 3 to 4 million fleeing the Red Army starting in 1944.10 Before the Potsdam Conference and Agreement, the first ethnic German expulsions and flights often were ad hoc, disorganized, and violent in nature.11 After the Potsdam Agreement stated that their expulsion was “to be effected in an orderly and humane manner,” these expulsions became more organized, yet still resulted in loss of possessions, harassment, and poor travel conditions.12 It is estimated that about 12 million entered Germany between 1945 and 1947.13 In the end, most of the expulsions and flights ended in 1949, leaving many ethnic Germans to settle into Germany or depart for areas like the U.S..14

Endnotes

- Lutheran World Federation, Lutheran World Federation Service to Refugees in Germany 1947-1949. Materials for Report, ed. Howard V. Hong, vol. 1, 1949.

- Valdis O. Lumans, Latvia in World War II, 1st ed, World War II–the Global, Human, and Ethical Dimension (New York: Fordham University Press, 2006), 138 http://catdir.loc.gov/catdir/toc/ecip0610/2006007965.html.

- Ibid.

- Valters Nollendorfs et al., “The Three Occupations of Latvia, 1940–1991: Soviet and Nazi Take-Overs and Their Consequences,” Museum of the Occupation of Latvia, 2005, 26.

- Ibid., 26. Latvia was also occupied from 1945-1991. Because of this, national consciousness concerning Soviet occupation is largely negative.

- Arūnas Bubnys, Matthew Kott, and Ülle Kraft, “The Baltic States: Auxiliaries and Waffen-SS Soldiers from Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania,” in The Waffen-SS: A European History, ed. Jochen Böhler and Robert Gerwarth (Oxford University Press, 2016), https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198790556.003.0005. For a more complete exploration of the complex issue of the participation of Baltic citizens in Waffen-SS and police auxiliary units please see Bubnys, Kott, and Kraft.

- Timothy Snyder, Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin (New York: Basic Books, 2010), 193.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, “Latvia,” Holocaust Encyclopedia, n.d., https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/jewish-population-of-europe-in-1933-population-data-by-country. - Bergen, Doris L. “The Nazi Concept of ‘Volksdeutsche’ and the Exacerbation of Anti-Semitism in Eastern Europe, 1939-45.” Journal of Contemporary History 29, no. 4 (1994): 569-82. http://www.jstor.org/stable/260679.

- Ibid, 572.

- Ulrich Merten, Forgotten Voices: The Expulsion of the Germans from Eastern Europe after World War II (New Brunswick, N.J: Transaction Publishers, 2012), 7-20.

- Ibid,

- Ibid, 10.

- Mark Wyman, DPs: Europe’s Displaced Persons, 1945-1951 (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2014), 20.

- Merten, Forgotten Voices, 20.

For a More In-Depth Understanding of Ethnic Germans/Volksdeutsche:

Click the button below to view the complete bibliography for this digital exhibition.

Photo Credits (from top to bottom, left to right)*

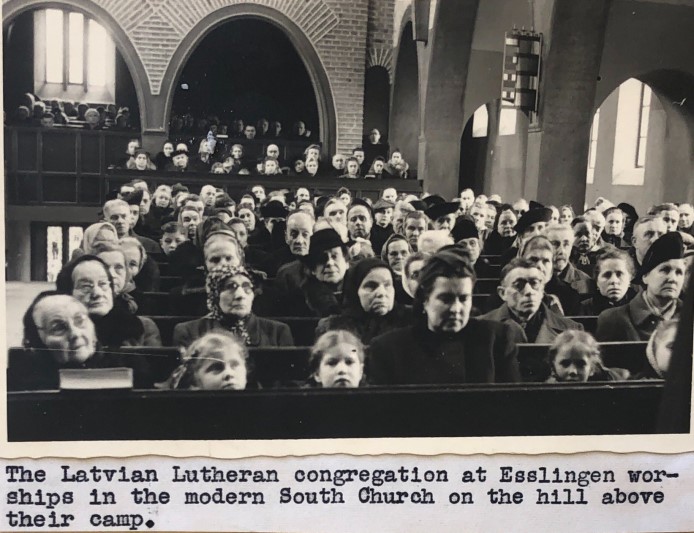

- Congregation sitting in pews, Lutheran World Federation Service to Refugees 1947-1949 Photographic Section, used with permission of the Lutheran World Federation and Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.

- A news flier regarding the Soviet occupation of Lithuania, likely propaganda, Jones, Adam. “File:Propaganda News Item on Soviet Takeover of Lithuania – Wikimedia.” Wikimedia Commons, November 17, 2017. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Propaganda_News_Item_on_Soviet_Takeover_of_Lithuania_-_Memorial_Museum_Adjacent_to_Ninth_Fort_-_Nazi_Genocide_Site_-_Kaunas_-_Lithuania_(27306653623)_(2).jpg.

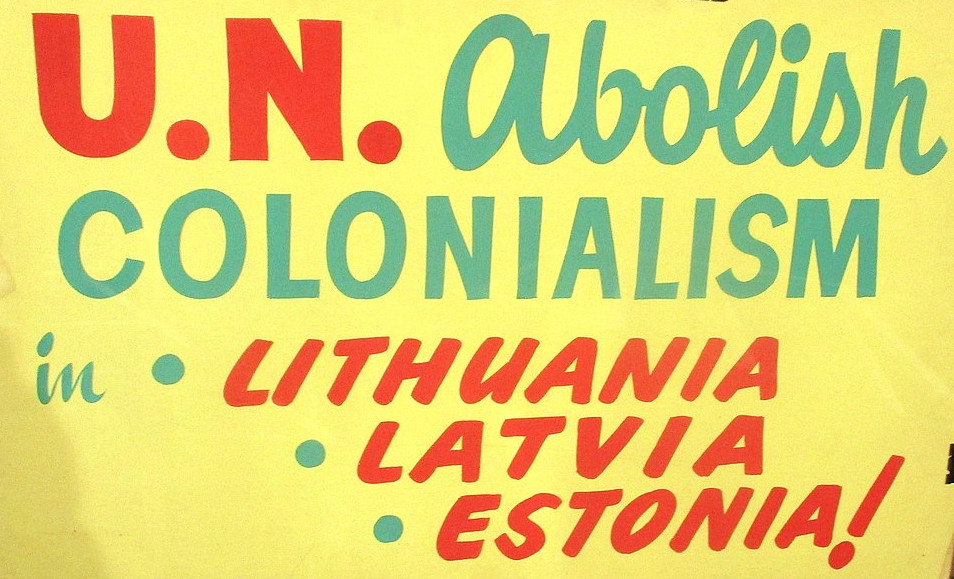

- A protest sign from a Baltic person in exile, calling on the U.N. to abolish Soviet colonialism in Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. From the exhibition “Nyet, nyet, Soviet! Political protests and demonstrations outside Latvia 1945-1991” at the Latvian Railway History Museum, Contributors to Wikimedia Projects. “File:Nyet, Nyet, Soviet.Jpg – Wikimedia Commons.” Wikimedia Commons, May 22, 2022. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nyet,_nyet,_Soviet_(11).jpg

- A crowd welcomes the Germans, expecting liberation from the Soviet Occupation. August 28th 1941, Tallinn, Estonia, Contributors to Wikimedia Projects. “File:Lentrée de Larmée Allemande En Estonie En 1941.” Wikimedia Commons, February 17, 2023. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lentr%C3%A9e_de_larm%C3%A9e_allemande_en_Estonie_en_1941_(7622403826).jpg

- “The Latvian SS Volunteer Legion on parade celebrating the 25th anniversary of National Latvia Day” November 1943, Contributors to Wikimedia Projects.“Category:Waffen-SS.” Wikimedia Commons, June 26, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_183-J16133,_Lettland,_Appell_der_SS-Legion.jpg

- “How most rural residents fled their homes ahead of the battlefront”, from: Ventis Plume, John Plume, and Vaira Vīke-Freiberga, Insula, Island of Hope: A Latvian Memoir, Revised and enlarged edition. (Morgan Hill, CA: Bookstand Publishing, 2013).

*Description ordering is based on computer view. If viewing this page on a smartphone or tablet, please check the descriptions provided as the ordering may be distorted.