Otonas Stanaitis

By Sophia HayesOverview

Otonas Edmundas Stanaitis was born May 28, 1905 in the village of Gaisriai in the county of Marijampolė, Lithuania.1 Stanaitis graduated from the University of Kaunas in 1930 and then received a scholarship to pursue his PhD in mathematics at the University of Würzburg in Germany. After completing his PhD, Stanaitis returned to Lithuania where he taught at various universities until the Soviet reoccupation of Lithuania in 1944.2 He and his family left Lithuania to live in Germany. A Northfield News article reported that Stanaitis attempted to get a teaching position in Germany, but was unable to due to not being on the “Nazi approved list.” Stanaitis and his family were still living in Germany when the Allied powers invaded, and in 1945 he and his family moved to a DP camp in Hanau, Germany, near Frankfurt am Main, where he taught mathematics at the camp’s secondary school.3 The DP camp was also where he first came into contact with Dr. Howard Hong, St. Olaf professor of philosophy and Senior Field Representative of the Lutheran World Federation Service to Refugees. After their meeting, Stanaitis worked with Hong and for the LWF-SR as a resettlement officer. Stanaitis once reflected on that time, saying that “Dr. Hong and I were so busy helping others immigrate to America that we just didn’t get around to my case until last August.”4 Indeed it was not until August 1949, roughly 4 years after arriving at the DP camp that Stanaitis and his family immigrated to Northfield, Minnesota.5 The Stanaitis family’s immigration was assured by St. Olaf College, where Otonas Stanaitis was awarded a position in the mathematics department.6 Stanaitis was employed at St. Olaf College until he retired in 1972 after 23 years of service. While living in Northfield, Stanaitis became a naturalized citizen in 1954.7 Following his retirement in 1972, Stanaitis relocated to Racine, Wisconsin, where an aunt of his lived. In fact, a number of other Baltic Lutheran refugees had also settled in Racine. Stanaitis passed away May 5, 1997 at the age of 91. He was survived at his death by his wife, Ona Stanaitis, two sons and two daughters-in-law; five grandchildren; seven great-grandchildren; and three sisters8.

At St. Olaf: 1949-1972

Otonas Stanaitis accomplished much and left a lasting impact on those he encountered while part of the St. Olaf community. In 1950, he presented at the Spring Conference of Minnesota Mathematics Teachers, less than a year after arriving in the United States.9 St. Olaf College’s student newspaper, the Manitou Messenger, reported on many more of Stanaitis’ academic achievements. In 1952, 1953, 1954, and 1955 he presented at the annual conference of the Minnesota chapter of the Mathematical Association of America.10 In 1953, Stanaitis worked closely with other St. Olaf faculty members, and was sponsored by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, to administer a survey which aimed to “study the role of the college in international relations and to discover ways and means, if possible, whereby the students may develop a greater international outlook, a better understanding, and a more significant interest in world affairs.”11

Multiple St. Olaf students remembered fondly their courses with Prof. Stanaitis. In 1952, student Jack Lysen wrote an article in the campus newspaper in which he recalled how he and his classmates “soon began to recognize the brilliance of the mind which deftly led us through the bewildering maze of mathematical theory” and that “every period, though nerve-racking, was enjoyable.”12 In 2017, alumnus Robert Rossi ’68 established an endowed scholarship in Stanaitis’ honor. In St. Olaf’s reporting on the matter, Rossi is cited saying, “I was always interested in math…but Professor Stanaitis taught me how to think — his lectures were beautiful; they opened another world for me. Although my primary major was physics, I ended up adding mathematics simply because of Stanaitis and the other fabulous instructors at St. Olaf.”13

Stanaitis and the Issue of Communism

For many Baltic refugees, the question of communism was a complex one, though not necessarily because refugees wavered between pro-communist and anti-communist feelings. Many Baltic refugees were vehemently anti-communist because they had lived under the Soviet regime. In the Baltic states, Soviet occupation was largely considered totalitarian in nature. There was a complete overhaul of Baltic life, and this overhaul was often enforced with violence, most prominently the Latvian “Year of Terror”, and the widespread deportation of Baltic citizens into the Gulag system, or Soviet labor camps.14 However, while many Baltic refugees to the United States already held anti-communist beliefs, this was not necessarily the perception that people living in the United States had of refugees from Eastern Europe. In fact, many people had to be convinced that these refugees were not communist sympathizers.15

This context surrounded Otonas Stanaitis in the years prior to and following his immigration to the United States. He maintained strong anti-communist sentiment in these years, and often at the same time sang the praises of American democracy. Stanaitis appeared to have a deep resentment towards the Soviet Union and its occupying forces. Upon his arrival in the United States, he described the conditions he lived under during the first Soviet occupation of Lithuania, saying that “in one year 30,00 Lithuanians answered knocks on their door at night and were never heard of again…We surmised they went to Siberian labor camps. Of course that is tantamount to death.”16 Other news articles about Stanaitis suggest that, at the time of his immigration to the United States, his mother had already died in a Siberian labor camp and he had another sister still imprisoned in one.17 This mention of “Siberian labor camps” likely refers to the Gulag. Stanaitis’ description of these camps is supported by the work of historians. Steven Barnes notes, for instance, that “any Gulag practices—if not specifically designed to cause prisoner deaths—were at least designed with little concern for the maintenance of prisoner lives.”18

Soviet occupation in the early 1940s had been so frightful for Stanaitis and his family that when the threat of reoccupation of Lithuania became a reality in 1944, they moved to Germany. On the matter of experience under German versus Soviet occupation, Stanaitis said that they suffered greatly under the Nazi regime, especially when Nazi leadership in Lithuania transitioned from military to administrative, but that even so, they never suffered as badly as they had under the Soviets.19 This was not an uncommon sentiment among Baltic citizens. For further information, visit the Occupation section of the website.

These experiences led to Stanaitis’ immigration to the United States and continued to impact the way he lived his life there. From very early on, he was a voice in academic circles about what it was like to teach under the Soviet regime. Less than a year after immigrating to the United States, he gave a talk at the Spring Conference of Minnesota Mathematics Teachers titled “Education Under the Russians.”20 A transcript of this talk is unavailable, but it is likely that it followed the vein of other public statements he made about his experience as an academic under Soviet rule. In a newspaper article, he was quoted lamenting the fact that even though he taught what he considered to be a non-political subject, he was still very much expected to “mouth Soviet philosophy” and he recalled distinct memories of having Soviet secret police in his classrooms, checking in to assure that he was falling in line.21

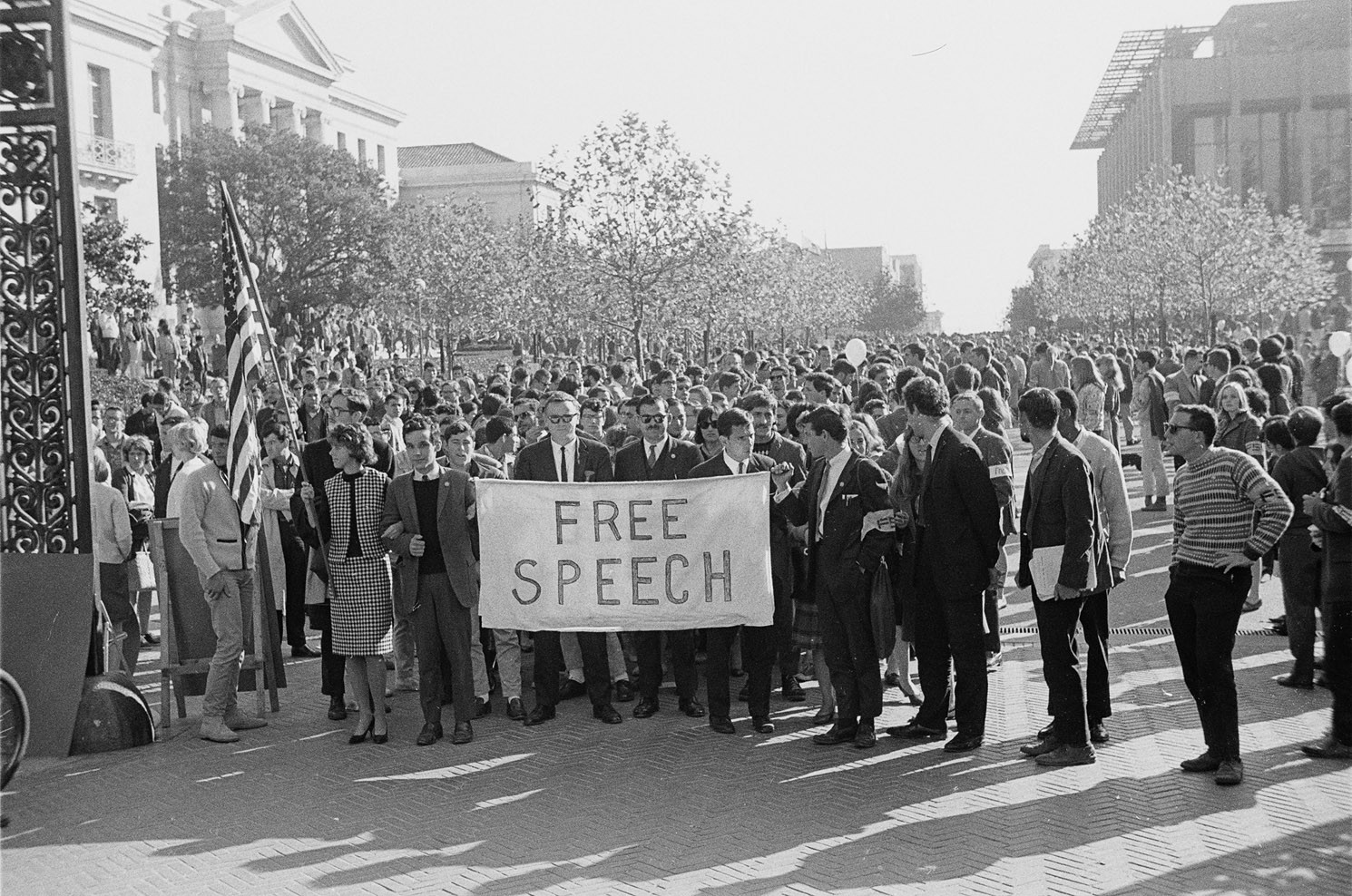

Such memories of those experiences of communism, and specifically the impact of Soviet occupation on academia, made an impression that carried forward into Stanaitis tenure at St. Olaf. On January 15, 1965 he published an op-ed in the Manitou Messenger titled “On Propaganda”.22 In this piece, he responds directly to the “student rebellion” at University of California-Berkeley, which began in September of 1964 and continued for the rest of the year.23 This, of course, refers to the Free Speech Movement, a mobilization of thousands of students of the University of California-Berkeley who sought to protest Berkeley’s orders that students could not hold political activities on or near campus (see left).24 Stanaitis cites the alleged communist connections of the Berkeley protests as evidence of the extent to which communist propaganda is proliferating in the United States. Offering a warning from his own experience, he recalls:

From 1930 till 1932 while a graduate student in Germany I saw both Communists and Nazis in action. Both groups used violence, the same kind of propaganda, attracted the same kind of “beatniks” and deranged minds. The academic community scoffed at Nazo [sic] propaganda, yet in 1933 Nazis became masters of Germany.25

Stanaitis seems to be warning his readers that if people continued to ignore the impact of communist propaganda, the United States might fall victim to a similar fate. He says so more directly with his sign off to the op-ed: “Therefore let us by no means underestimate the power of professional propaganda and learn from past experience. He who does not learn from history, repeats it!”

This was not the last time that Stanaitis would write about communism on campus and his worries about its spread in the United States, nor was it the last time he would imbue these arguments with reflections on his own history living under communism. Stanaitis wrote two more op-ed pieces tackling the same issues that year for the Manitou Messenger, one in April and one in May, titled “Stanaitis speaks out on debate Over confused Vietnam issue” and “Stanaitis asks: are US educators Blind to threat of communism?”, respectively.26

In the April article, Stanaitis addresses what he perceives as the United States’ failings in dealings with communism. He refers back to the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt, claiming that FDR made too many concessions to Stalin, and even suggests that some of the advisers who aided him in those decisions were themselves communists. Stanaitis argues that if FDR had not made those concessions, and if his successors had not failed to fix his mistakes, the Korean War and “the dreadful danger we now face of a war with Red China” could have been avoided.27 He furthermore criticizes professors who “joined the communist line” by signing a letter to the US President supporting a ceasefire in Vietnam, and compared the “terror” of Vietnam to that of Lithuania while under Soviet occupation.

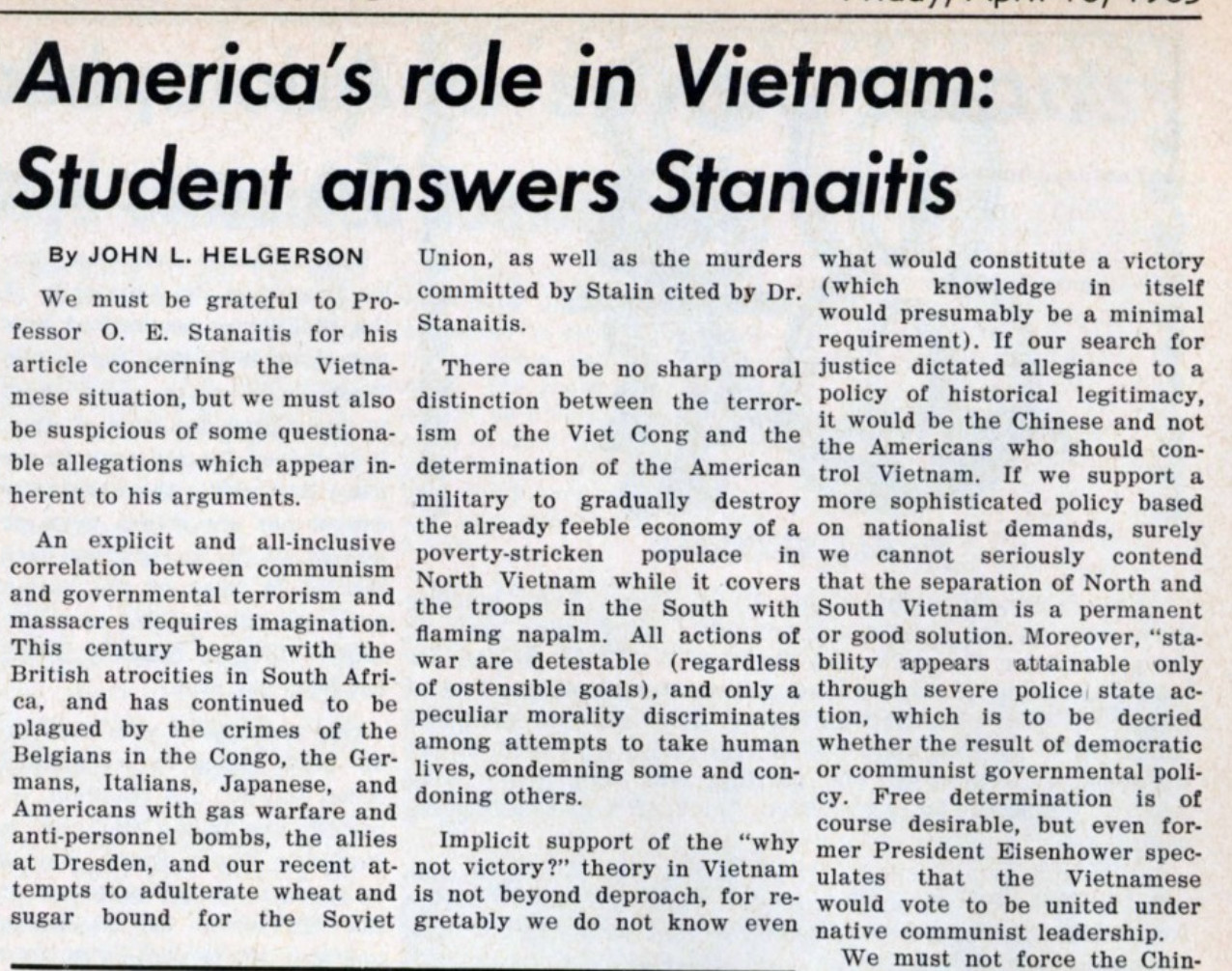

Stanaitis’s op-eds garnered responses from two students, Lowell Satre ‘68 and John L. Helgerson ‘66. Satre expresses concern about the “extremely dangerous technique” asserting that those whose opinions sometimes aligned with the Communist party were presumed to be communists or communist sympathizers.28 Both Satre and Helgerson challenge the comparisons Stanaitis draws between his own situation and what was happening in Vietnam.

Stanaitis’ final article may have been influenced by such responses to his earlier writings, though it is not known for sure. In his last op-ed, he reaffirms his worries about communism on college campuses, citing examples from a “sister campus” of St. Olaf College, or possibly a “sister campus” as well as St. Olaf. He claims that in these spaces, the college papers were full of communist propaganda, and goes so far as to say that “on the campus exists a subversive cell connected with the Communists.”29 Stanaitis does not appear to have published in the Messenger for the remainder of his career at St. Olaf. Nor have further sources emerged to inform us about how his thinking about communism and his fear of its spread may have later evolved. What sources are available suggest the depth of trauma experienced while living under Soviet occupation. Also, as mentioned previously, it may be that his public stance was hardened by the necessity to appear as anti-communist as possible so as to be accepted as an Eastern European immigrant in the US at the start of the Cold War.

Enduring Resonances

Stanaitis’ experiences and writings allow us to deepen our understanding of the complex ways in which people continue to think about, talk about, and experience communism. Consider, for instance, efforts to legally ban the social media app TikTok, which some politicians see as a “weapon in the hands of Communist China.”30 Anti-communist arguments we see today are frequently laden with xenophobia and sinophobia. Still, the perspective of Stanaitis reminds us that for some, the threat of communism is very real, a personal matter based in violent, lived experience. While we are still allowed to probe the implications of anti-communist rhetoric, cases like Stanaitis’ offer nuance to an often polarized conversation.

Stanaitis’ expressions in the college newspaper also resonate with present debates over academic freedom. Stanaitis wrote those articles as an appeal to the college community, and we know that at least one student took personal offense to those writings. We find ourselves now in a time when academic freedom is a point of high contention, whether it is a matter of faculty members expressing their personal beliefs, as Stanaitis did, or a matter of examining topics in scholarship that are known to provoke controversy.

At St. Olaf College in 2022, a controversy arose around the college’s Institute for Freedom and Community when it was alleged that Professor Edmund Santurri was prematurely removed from his position as Director of the Institute after the IFC hosted a talk by philosopher Peter Singer. The speaker event was met with disdain and anger by many students. Yet, in a letter to then President David Anderson, a representative of the Academic Freedom Alliance, Keith Whittington, warned that Dr. Santurri’s removal “sends a clear message to the campus that some exploration of ideas will not be tolerated and that the college’s stated promise that the faculty will have the full freedom to pursue the truth in accord with their scholarly judgment is a hollow one.”31 Stanaitis was able to publish his thoughts on communism freely in 1965, with no known professional repercussions. Would he have been able to do the same in 2024? Should he be able to? Revisiting his writings and his personal story allow us to expand our understanding of the meaning of academic freedom both at St. Olaf and in the larger sphere of academia.

Finally, it is worth noting that Stanaitis was critical of the student demonstrations at Berkeley and across the country. Though they occurred nearly 60 years ago, political demonstrations by college students remain a practice and a major topic of public discussion. The relevance of that history is especially pronounced today as we see student protests and encampments similar to those of the Vietnam era spread across the country in support of a free Palestine. Demonstrations large and small have taken place on St. Olaf’s own campus. Hundreds of students gathered on April 30, 2024 to denounce St. Olaf’s investment in the company Oracle and to stand in solidarity with the people of Palestine. As in the 1960s, there have been negative reactions to the demonstrations on St. Olaf’s campus and beyond, as well as a rash of support for the young students willing to take a stand. There is tension between those who want to empower students who choose to organize and those who see need to limit them. Prof. Stanaitis’ writings about the demonstrations of 1965 are a provocative piece of the larger history of student protest and their wider contexts at St. Olaf and beyond.

Anecdotes from Friends, Colleagues, and Students

As part of the research for this page, we were fortunate to communicate with some of Stanaitis’ former colleagues and students, and we thank them for their contributions. Here are some highlights from their memories of Otonas Stanaitis and his family:

From Emeritus Professor James Cederberg:

Although they and their two sons arrived with very few belongings, they were able to build the house [near campus]…and by thrift and shrewd investment were able to manage even with the limited St. Olaf salary. … They were always very cordial, and often invited me to join them for a Sunday dinner of potato pancakes and a game of Scrabble.32

From Bob Rossi ’68:

I took multiple classes taught by Dr. Stanaitis. Why was he my favorite teacher? I learned something from every lecture, and he opened my mind to new ways to look at problems. He was all mathematics to his students… Dr. Stanaitis would always enter five minutes late at the back of the classroom, walk to the front, and start writing on that blackboard to begin his lecture. One day, I told the ten students in the class, “Let’s turn all the desks around and sit as we normally do. What do you think Dr. Stanaitis will do?” We did it. Dr. Stanaitis entered the room, looked around, and left. Five minutes later (the longest five minutes of my life), he re-entered, started writing on the blackboard that was in the back by the door, and began his lecture.33

Endnotes

- Gintarė Viselgiene, “Otonas Stanaitis,” in Universal Lithuanian Encyclopedia, n.d., https://www.vle.lt/straipsnis/otonas-edmundas-stanaitis/.

- “From DP Camp to Professorship at College Is Good Fortune of Lithuanian,” n.d.

- “Another Dp Family Arrives-Lithuanian Professor to Teach at St. Olaf This Fall,” n.d.

- Staff Writer, “Refugee from Lithuania Now a Member of St. Olaf Faculty Appreciates U. S.,” St. Paul Sunday Pioneer Press, October 20, 1949.

- Ibid.

- “St. John’s DP Resettlement Reports 48-50 32” (St. John’s Lutheran Church, n.d.), Box 3, St. John’s Church Archives.

- “Minnesota Naturalization Card Index, 1930-1988”, , FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:24YW-V12 : Sun Mar 10 16:06:53 UTC 2024), Entry for Otonas Edmundas Stanaitis, 1954.

- “Obituary: Otonas Stanaitis,” The Journal Times, May 7, 1997, https://journaltimes.com/news/local/obit-otonas-e-stanaitis/article_af78fc89-388c-5418-b017-ad54a39cf1a2.html.

- “State Mathematics Teachers to Hold Conference at ‘U’” (University of Minnesota News Service, May 1, 1950), https://conservancy.umn.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/aff4e989-c4c6-484e-9055-be6739f0e4da/content, 140.

- “Dr. Stanaitis’ Work Read at St. Kate’s,” St. Olaf Manitou Messenger, May 9, 1952. St. Olaf College Archives, https://stolaf.eastview.com/browse/doc/45944739/dr-stanaitis-work-read-at-st-kate-s.

“Stanaitis Speaks On Convergence At Math Meeting,” The Manitou Messenger, October 15, 1954. St. Olaf College Archives, https://stolaf.eastview.com/browse/doc/45945601.

“Math Group Hears Stanaitis Remarks,” The Manitou Messenger, October 9,1953. St. Olaf College Archives, https://stolaf.eastview.com/browse/doc/45944425. - “Faculty Committee Appraises Student ‘International Outlook,’” The Manitou Messenger, November 19, 1954. St. Olaf College Archives, https://stolaf.eastview.com/browse/doc/45947605.

- Jack Lysen, “If It’s Math, He Knows the Answer,” The Manitou Messenger, October 3, 1952, St. Olaf College Archives, https://stolaf.eastview.com/browse/doc/45949491.

- Dan Riehle-Merrill, “Robert Rossi ’68: Grateful for Opportunities,” October 2, 2017, https://wp.stolaf.edu/news/robert-rossi-68-grateful-for-opportunities.

- Valdis O. Lumans, Latvia in World War II, 1st ed, World War II–the Global, Human, and Ethical Dimension (New York: Fordham University Press, 2006), http://catdir.loc.gov/catdir/toc/ecip0610/2006007965.html, 138.

Alain Blum and Emilia Koustova, “A Soviet Story: Mass Deportation, Isolation, Return,” in Narratives of Exile and Identity: Soviet Deportation Memoirs from the Baltic States, ed. Violeta Davoliūtė and Tomas Balkelis (Central European University Press, 2018), 19–40, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7829/j.ctv4cbhvq.7, 20. - Lutheran World Service, St John’s Lutheran Church Archive, Northfield, MN, Box 3.

- Staff Writer, “Refugee from Lithuania Now a Member of St. Olaf Faculty Appreciates U. S.,” St. Paul Sunday Pioneer Press, October 20, 1949.

- “From DP Camp to Professorship at College Is Good Fortune of Lithuanian,” n.d.

- Steven Barnes, “The Origins, Functions, and Institutions of the Gulag,” in Death and Redemption: The Gulag and the Shaping of Soviet Society (Princeton University Press, 2011), 7–27, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt7pgms.6, 18.

- Staff Writer, “Refugee from Lithuania Now a Member of St. Olaf Faculty Appreciates U. S.,” St. Paul Sunday Pioneer Press, October 20, 1949.

- “State Mathematics Teachers to Hold Conference at ‘U’” (University of Minnesota News Service, May 1, 1950), https://conservancy.umn.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/aff4e989-c4c6-484e-9055-be6739f0e4da/content, 140.

- Staff Writer, “Refugee from Lithuania Now a Member of St. Olaf Faculty Appreciates U. S.,” St. Paul Sunday Pioneer Press, October 20, 1949.

- Otonas Stanaitis, “On Propaganda,” The Manitou Messenger, January 15, 1965, St. Olaf College Archives, https://stolaf.eastview.com/browse/doc/46103673.

- “Free Speech Movement,” Berkeley Library, n.d., https://www.lib.berkeley.edu/visit/bancroft/oral-history-center/projects/free-speech-movement.

- Karen Aichinger, “Berkeley Free Speech Movement,” University of Tennessee Free Speech Center, January 1, 2009, https://firstamendment.mtsu.edu/article/berkeley-free-speech-movement/.

- Otonas Stanaitis, “On Propaganda,” The Manitou Messenger, January 15, 1965, St. Olaf College Archives, https://stolaf.eastview.com/browse/doc/46103673.

- Otonas Stanaitis, “Stanaitis Speaks Out on Debate Over Confused Vietnam Issue,” The Manitou Messenger, April 9, 1965, St. Olaf College Archives, https://stolaf.eastview.com/browse/doc/46103557.

Otonas Stanaitis, “Stanaitis Asks: Are US Educators Blind to Threat of Communism?,” The Manitou Messenger, May 7, 1965, St. Olaf College Archives, https://stolaf.eastview.com/browse/doc/46103766. - Otonas Stanaitis, “Stanaitis Speaks Out on Debate Over Confused Vietnam Issue,” The Manitou Messenger, April 9, 1965, St. Olaf College Archives, https://stolaf.eastview.com/browse/doc/46103557.

- Lowell Satre, “Opposition to Vietnam Policy Similar to Communism?,” The Manitou Messenger, April 16, 1965, St. Olaf College Archives, https://stolaf.eastview.com/browse/doc/46103638.

- Otonas Stanaitis, “Stanaitis Asks: Are US Educators Blind to Threat of Communism?,” The Manitou Messenger, May 7, 1965, St. Olaf College Archives, https://stolaf.eastview.com/browse/doc/46103766.

- Marsha Blackburn, “Communist China Has Weaponized TikTok Against America. Now, Congress Must Act.,” March 25, 2024, https://www.blackburn.senate.gov/2024/3/communist-china-has-weaponized-tiktok-against-america-now-congress-must-act.

- Colleen Flaherty, “Academic Freedom: Fallout From Peter Singer Talk at St. Olaf,” Inside Higher Ed, April 25, 2022, https://www.insidehighered.com/quicktakes/2022/04/26/academic-freedom-fallout-peter-singer-talk-st-olaf.

Academic Freedom Alliance and Keith Whittington, “Letter to President David Anderson,” April 25, 2022, https://academicfreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/AFA-Letter-to-St-Olaf-College-regarding-the-Institute-for-Freedom-and-Community.pdf. - James Cederberg, e-mail exchange with Amanda Randall and Sophia Hayes, April 2024.

- Bob Rossi, e-mail exchange with Amanda Randall and Sophia Hayes, April 2024.

Photo Credits (from top to bottom, left to right)*

- Otonas Edmundas Stanaitis, Universal Lithuanian Encyclopedia, https://www.vle.lt/straipsnis/otonas-edmundas-stanaitis/. Used with permission.

- November 1959: St. Olaf and Carleton Professors with Carleton’s First Computer, 1959, Collection 3: Photographic Prints, Series 5 1959/60, Computing, Carleton College Archives, https://archive.carleton.edu/Detail/collections/9385. Used with permission.

- “Refugee from Lithuania Now a Member of St. Olaf Faculty Appreciates U. S.,” St. Paul Sunday Pioneer Press, October 20, 1949, St. John’s Church Archives. Used with permission.

- Steven Marcus, Marchers Coming through Sather Gate with Free Speech Sign to the UC Regents’ Meeting in University Hall to Present Their Position on the Free Speech Controversy., November 20, 1964, Steven Marcus Free Speech Movement Photographs, circa 1964, The Bancroft Library at University of California-Berkeley, https://digicoll.lib.berkeley.edu/record/54191?ln=en&v=uv#?xywh=-317%2C-56%2C2120%2C1097. Used with permission.

- John Helgerson, “America’s Role in Vietnam: Student Answers Stanaitis,” The Manitou Messenger, April 16, 1965, St. Olaf College Archives, https://stolaf.eastview.com/browse/doc/46103634.

- Megan Lu, Students on Mellby Lawn Gather in Support for Palestine, April 30, 2024, https://www.theolafmessenger.com/2024/student-expression-on-campus-sjp-hosts-rally-for-palestine/. Used with permission.

*Description ordering is based on computer view. If viewing this page on a smartphone or tablet, please check the descriptions provided as the ordering may be distorted.