Images of War

When viewing images of bombed cities, kamikaze pilots, or the mushroom cloud rising over Hiroshima, it is impossible to deny the significant impact that World War II had on Japan. While these grainy black and white photographs provide us with an image of the war’s effect on society, looking at Japanese woodblock prints can give an equally valuable understanding. Examining the Japanese woodblock prints created before, during, and after World War II gives excellent insight into the minds and experiences of not only the artists themselves, but also Japanese society at large. By looking primarily at the work and life of Toshi Yoshida, and supplementing it with the experiences of other woodblock printers, we can perhaps better understand how World War II affected Toshi, woodblock printers in general, and the nation as a whole.

Prior to the rise of Japan’s military dictatorship, the country’s artists had discovered and embraced “Western-style art” during the Meiji Restoration and during the “growing liberalization” of the 1920’s. Although many artists started experimenting with new styles, the most popular prints abroad were those that showed peaceful landscapes. Art collectors in the United States and Europe got their hands on as many woodblock prints as they could, and the artists provided them with, “scenes that confirmed their romantic vision of Japan as an exotic land unsullied by the trappings of industrialization”. Peaceful gardens, beautiful geishas, and views of Mt. Fuji were all popular exports to the West.

As Japan’s authoritarian military government came to power, however, there was a true threat to artistic individuality and creativity. Additionally, “as the Japanese took over Manchuria” and Japanese “hovered over China in the late 1930s, Westerners began to look upon exotic views of torii gates and geisha with less enchanted eyes.” However, while the international market for traditional Japanese prints dried up, “nationalistic feelings, stimulated by the military advances in China” allowed artists to sell prints of patriotic Japanese themes to the home market.

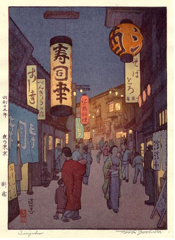

Prints like Toshi Yoshida’s 1938 Shinjuku [fig. 1] depict traditionally dressed women walking through a market street at night. Warm lights come from the windows, and there is no evidence of anything European. Although this print may sound peaceful and romantic, it is a hint at the popular opinion that promoted agreement with the state. Many people in Japan refer to the 1930’s as “The Dark Valley” and see it as a time of “suspicion, narrow-minded nationalism, and growing conformity” in which avant-garde artists “soon found themselves out of favor”. One academic explains that, “even in the midst of ‘The Dark Valley,’ however, Japanese art managed to retain much of its diversity and vitality. It never took on the deadly uniformity seen in art from Stalinist Russia or Nazi Germany”.

Although Japanese conformity may not have quite reached the levels of Nazi Germany, there were many similarities between how the war affected art in the two countries. Furthermore, in many instances Japanese leaders “modeled” their decisions on the “Nazi Propaganda Ministry”.Creativity and individuality were not ideals the new Japan would promote; instead art was to be created “not for its own sake, but in service to the Japanese race”. These values eerily echo those of Nazi Germany, and as war intensified, the government and military would have ever-increasing control over artistic production. Some in the government complained that Japanese artists were the last to help in the “ideological warfare” because they were too self interested. Additionally, the military explained that in order for art to be “meaningful” it needed “to have wide appeal and be grounded in universal relevance… good art was reflective of commonly held racial and national values”. Indeed the government needed artists, but only to produce “patriotic war images”.

This push for patriotic images is apparent in many facets of Japanese war culture, and indeed touched the lives of most artists. In an art guide produced by the Japanese government, the bias for traditional and patriotic artwork is very apparent. The manual states that traditional, “Japanese color prints” are “definitely above those of any other country on earth. And the best representatives of these superior Japanese prints are those produced in the period beginning with 1765 and ending, say, with 1800”. The government push of patriotic images even touched the life of Toshi Yoshida. Toshi’s father, “made three trips to China to make postcards for soldiers’ morale, but otherwise his printmaking activities were curtailed by the war”. For Toshi, “the war cut the Yoshida studio off from its most important market, the growing number of print connoisseurs in the United States”. During the war, Toshi produced several patriotic works, including one oil painting entitled, Sailing Ships Between Japan and Taiwan. The painting depicts a ship on the lookout for American submarines, and exudes a calm that implies that “at the center of the war effort Toshi saw both strength and repose”. Although he created a few such pieces, for the most part his efforts like those of many other artists were hampered by the “shortage of materials.” Ultimately, it was the three-part effect of an authoritarian government, the loss of western demand, and a loss of supplies that caused the war to drastically effect Japanese artists.

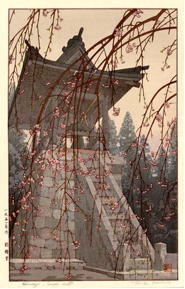

When the war ended in 1945 and Allied troops took control of Japan, there was significant change in Japanese woodblock prints; in fact “World War II and the American Occupation that followed set in motion changes that were as drastic in their way as those that had taken place at the start of the Meiji Period”. Although the period of occupation was a time of hardship for many Japanese, it also flowered into a “bloodless cultural and social revolution” where “the occupying forces pushed through a series of reforms” that would affect all of Japan. Additionally, the occupying American troops provided incredible financial support for a rebirth of woodblock printing in Japan. Many artists were able to gain popularity by “holding open house events for American service personnel and their wives” and showing off their art to the very people that they had been fighting against. Because of this support, many artists had a “newfound freedom” which “allowed their art to expand in directions that would have seemed impossible before the war” and allowed for some artists to experiment more with abstract art, which had been suppressed by the ousted military regime. Although Toshi Yoshida would eventually experiment with abstractions, he still produced many traditional pieces after the war ended. As Toshi Yoshida scholar Skibbe explains, “the subject of the first prints was springtime, and the new style in which they were done was a lovely springtime as well. In 1951 alone Toshi produced seventeen landscape and genre prints. Most of these explore, not tourist sites, but the common realities beautiful to the Japanese heart.” Perhaps one of the best depictions of this “lovely springtime” is a woodblock print entitled Heirinji Temple Bell [fig. 2] produced in 1951. In the foreground is a blossoming tree branch, which partially covers the ancient bell tower. In the tower, a proud monk faces away from the viewer, and rings the bell. This very Japanese image indicates that despite living through a long hard war, Toshi is still a proud Japanese artist at heart.

Bibliography

Huzikake, S. Japanese Wood-Block Prints. Board of Tourist Industry. Tokyo, 1938

Jenkins, Donald. Images of a Changing World: Japanese Prints of the Twentieth Century. Portland Art Association, 1983

Merritt, Helen. Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints: The Early Years. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu. 1990

Sandler, Mark H. The living artist: Matsumoto Shunsuke’s reply to the state.(Japan 1868-1945: Art, Architecture, and National Identity.) In Art Journal 9/22/06. Gale Group, Farmington Hills MI.

Skibbe, Eugene. Yoshida Toshi: Nature, Art, and Peace. Seascape Publications,Edina MN.

Appendix

#1: Shinjuku

Toshi Yoshida, 1938

#2: Hierinji Temple Bell

Toshi Yoshida, 1951

Jenkins, Donald. Images of a Changing World: Japanese Prints of the Twentieth Century. Portland Art Association, 1983, page 7

Merritt, Helen. Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints: The Early Years. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu. 1990, page 67

Sandler, Mark H. The living artist: Matsumoto Shunsuke’s reply to the state.(Japan 1868-1945: Art, Architecture, and National Identity.) In Art Journal 9/22/06. Gale Group, Farmington Hills MI.

Huzikake, S. Japanese Wood-Block Prints. Board of Tourist Industry. Tokyo, 1938. page 60

Skibbe, Eugene. Yoshida Toshi: Nature, Art, and Peace. Seascape Publications,Edina MN. 1996 page 45