Volume I

With its hot springs and ancient Roman baths, the city of Bath has a long history as a popular spa town. Originally, the sick visited to drink the town’s waters, which many people believed to have medicinal qualities. During the Georgian era, Bath’s popularity grew and it became an increasingly fashionable place to socialize. A late eighteenth-century Bath guidebook entitled The New Bath Guide; Or, Useful Pocket Companion (1784) explains that Bath was “originally a resort of . . . diseased persons” but that Master of Ceremonies Richard Nash transformed the city into a place of amusement “as much frequented by the gay and healthy for their pleasure, as the sick for their health.”

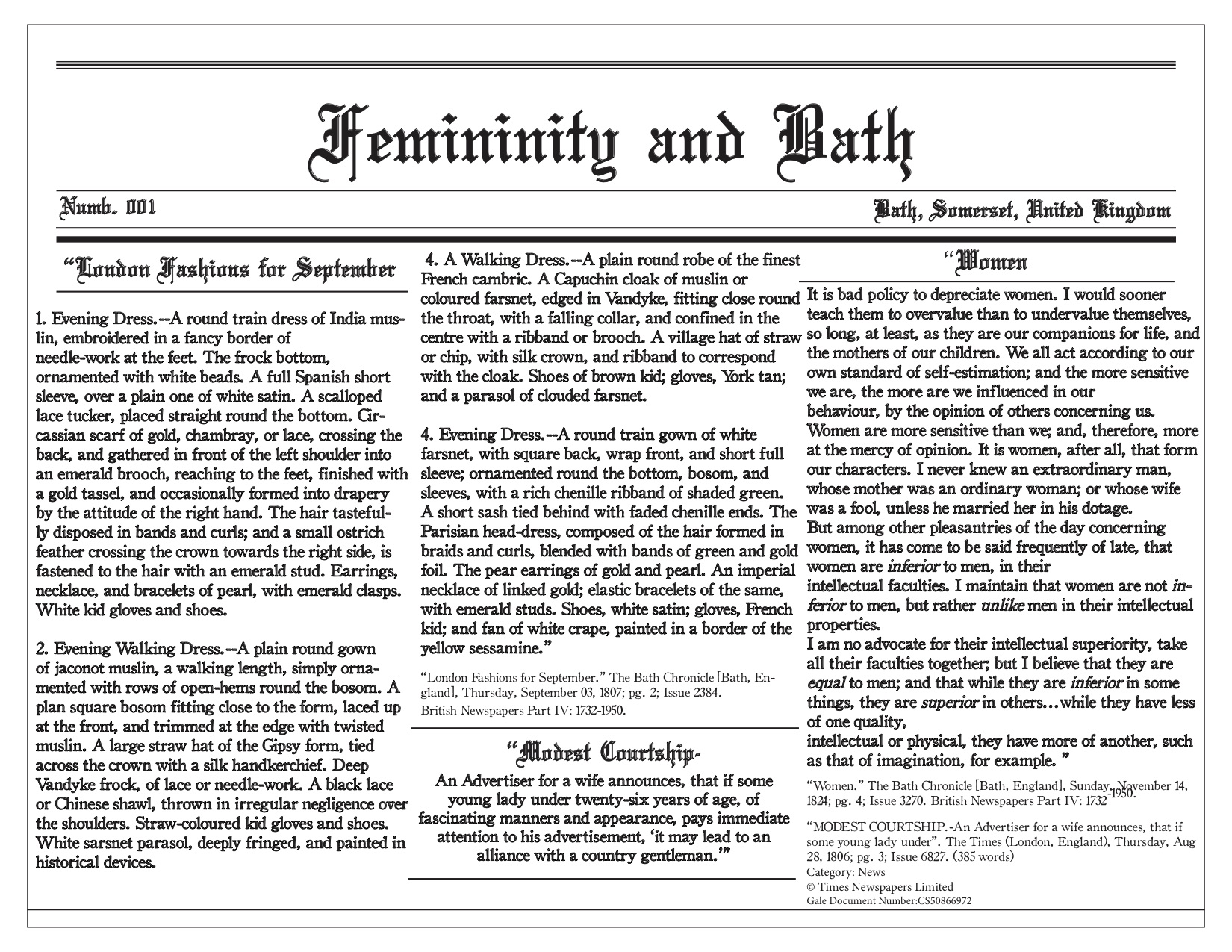

Francis Place. “City of Bath.” 1678. [Public Domain] via Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. http://collections.britishart.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3647411.

While these elegant amusements attracted many of Britain’s elite to the city, they also drew scorn from satirists of the time. Austen herself critiques Bath’s fashion culture in her letters to her sister Cassandra. In a May 1801 letter, she writes, “Another stupid party last night; perhaps if larger they might be less intolerable, but here there were only just enough to make one card table, with six people to look on, & talk nonsense to each other.” She goes on to describe one guest as “any other short girl with a broad nose & wide mouth, fashionable dress, & exposed bosom.” Austen’s personal dislike for the spa town (and its tendency to expose female vices in particular) permeates Northanger Abbey as well, from Mrs. Allen’s preoccupation with fashion to Isabella’s constant flirtation.

The manners and mores of Austen’s time affected both men and women, but they were often manifestations of gender inequalities and assumptions that disproportionately regulated women. For example, Austen frames a visit to the Pump Room in gendered terms: “Mr. Allen, after drinking his glass of water, joined some gentlemen to talk over the politics of the day and compare the accounts of their newspapers; and the ladies walked about together, noticing every new face, and almost every new bonnet in the room” [50].

At the same time, women like Austen were finding a new degree of autonomy in cities like Bath, coinciding with their growing sense of agency as readers and writers of the early novel. Describing how Catherine and Isabella choose to spend their time, Austen writes, “if a rainy morning deprived them of other enjoyments, they were still resolute in meeting in defiance of wet and dirt, and shut themselves up, to read novels together” [23]. Indeed, Catherine’s trip to Bath not only introduces her to the rules of fashion and courtship; it also introduces her to new people and lifestyles. In judging the relative merits and flaws of these new people, Catherine cultivates her growing independence of thought. For example, she forms her own opinion of John Thorpe despite the way others praise him:

“Little as Catherine was in the habit of judging for herself, and unfixed as were her general notions of what men ought to be, she could not entirely repress a doubt, while she bore with the effusions of his endless conceit, of his being altogether completely agreeable. It was a bold surmise, for he was Isabella’s brother; and she had been assured by James that his manners would recommend him to all her sex; but in spite of this, the extreme weariness of his company, which crept over her before they had been out an hour, and which continued unceasingly to increase till they stopped in Pulteney Street again, induced her, in some small degree, to resist such high authority, and to distrust his powers of giving universal pleasure” [47].

Below, an essay from The Mirror, an eighteenth-century conduct periodical mentioned in Northanger Abbey, models the pervasiveness of fashion culture in cities such as Bath. Then, a set of newspaper articles from The Bath Chronicle displays Georgian Bath as a place that confined women to fashion and courtship standards, but also opened new possibilities for them to engage in intellectual pursuits of their own. Finally, a timeline featuring period works of visual satire shows the ways in which artists in Austen’s day critiqued Bath’s fashionable society, echoing the commentary in Austen’s letters and Northanger Abbey.

Digital Copy of The Mirror courtesy of Internet Archive

The Mirror

On the left is a digital copy of The Mirror, a popular conduct magazine published through the Edinburgh Review every Tuesday and Saturday in 1779 and 1780. Circulating in Austen’s lifetime, The Mirror is explicitly mentioned by Mrs. Morland in Northanger Abbey:

“There is a very clever Essay in one of the books up stairs upon much such a subject, about young girls that have been spoilt for home by great acquaintance–“The Mirror,” I think. I will look it out for you some day or other, because I am sure it will do you good.” [178]

According to Austen scholars, Mrs. Morland is referring to Essay No. 12 from Saturday, March 6, 1776, entitled, “To the Author of The Mirror”, which begins on page 76 of the text [1], and is available in full-text using the embedded copy here or by visiting the Internet Archive website.

The Mirror frames fashion as a threat to both country and religion. Fashion is not only frivolous, but capable of making young women prefer French phrases to English, and even doubt the immortality of the soul. It will, as the author writes, “bring our estates to market, our daughters to ruin, and our sons to the gallows” [82]. Despite extensive caution in The Mirror, why might Mrs. Morland remain “wholly unsuspicious” of the city’s threat to Catherine’s morality [9]?

Given the dominance of muslin within Bath fashion, as seen from newspaper articles to caricatures, it is not surprising that the cloth should loom large within Austen’s Northanger Abbey. However, given that the trend was only possible through imperial England’s trade with India, Austen’s frequent mention of muslin betrays a subtle critique not only of the frivolity of fashion but also the politics of empire.

Map Instructions: In order to view the embedded series of maps, please click on the “start exploring” button and use the arrows. You should begin with the map entitled, “Muslin in the Indian Subcontinent,” continue to “Muslin in London,” and finish with “Muslin in Bath.” Markers for specific locations will appear when you hover your cursor over the map on each slide. The marker for the slide that you are currently viewing appears in red.